2.1 Cognitive and Social- cognitive theories( Piaget, Vygotsky, Bandura)

Piaget's theory of cognitive development

Piaget's theory of cognitive development is a comprehensive theory about the nature and development of human intelligence. It was first created by the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980). The theory deals with the nature of knowledge itself and how humans gradually come to acquire, construct, and use it. Piaget's theory is mainly known as a developmental stage theory.

To Piaget, cognitive development was a progressive reorganization of mental processes resulting from biological maturation and environmental experience. He believed that children construct an understanding of the world around them, experience discrepancies between what they already know and what they discover in their environment, then adjust their ideas accordingly. Moreover, Piaget claimed that cognitive development is at the center of the human organism, and language is contingent on knowledge and understanding acquired through cognitive development. Piaget's earlier work received the greatest attention.

Nature of intelligence: operative and figurative

Operative intelligence is the active aspect of intelligence. It involves all actions, overt or covert, undertaken in order to follow, recover, or anticipate the transformations of the objects or persons of interest. Figurative intelligence is the more or less static aspect of intelligence, involving all means of representation used to retain in mind the states (i.e., successive forms, shapes, or locations) that intervene between transformations. That is, it involves perception, imitation, mental imagery, drawing, and language. Therefore, the figurative aspects of intelligence derive their meaning from the operative aspects of intelligence, because states cannot exist independently of the transformations that interconnect them. Piaget stated that the figurative or the representational aspects of intelligence are subservient to its operative and dynamic aspects, and therefore, that understanding essentially derives from the operative aspect of intelligence.

At any time, operative intelligence frames how the world is understood and it changes if understanding is not successful. Piaget stated that this process of understanding and change involves two basic functions: assimilation and accommodation.

Assimilation and accommodation

To Piaget, assimilation meant integrating external elements into structures of lives or environments, or those we could have through experience. Assimilation is how humans perceive and adapt to new information. It is the process of fitting new information into preexisting cognitive schemas.

Piaget's understanding was that assimilation and accommodation cannot exist without the other. [18] They are two sides of a coin. To assimilate an object into an existing mental schema, one first needs to take into account or accommodate to the particularities of this object to a certain extent. For instance, to recognize (assimilate) an apple as an apple, one must first focus (accommodate) on the contour of this object. To do this, one needs to roughly recognize the size of the object. Development increases the balance, or equilibration, between these two functions. When in balance with each other, assimilation and accommodation generate mental schemas of the operative intelligence. When one function dominates over the other, they generate representations which belong to figurative intelligence.

|

• Schemas: A specific structure or organized way of making sense of experience (like clicking images). • Adaptation: The process of building schemes through direct interaction with environment. Made up of two complementary activities: assimilation and accommodation. • Assimilation: Part of adaptation in which external world is interpreted in terms of current schemes. Where new knowledge is understand in relationship to previous knowledge. • Accommodation: Part of adaptation in which old schemes are adjusted and new ones created to produce a better fit with the environment. Where existing knowledge does not fit to the new knowledge in any way and so the existing knowledge is changed. • Equilibration: Back-and-forth movement between cognitive equilibrium and disequilibrium throughout development, which leads to more effective schemes.

|

All children pass through a series of universal stages in a fixed order:

1. Sensorimotor - birth to 2 years

2. Preoperational -2 to 7 years

3. Concrete operations -7 to 11 years

4. Formal operations -11 years to older

1. The Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to 2 years)

It is the first of the four stages in cognitive development which "extends from birth to the acquisition of language". In this stage, infants progressively construct knowledge and understanding of the world by coordinating experiences (such as vision and hearing) with physical interactions with objects (such as grasping, sucking, and stepping). Infants gain knowledge of the world from the physical actions they perform within it. They progress from reflexive, instinctual action at birth to the beginning of symbolic thought toward the end of the stage.

In this stage, according to Piaget, the development of object permanence is one of the most important accomplishments. Object permanence is a child's understanding that objects continue to exist even though he or she cannot see or hear them. Peekaboo is a good test for that. By the end of the sensorimotor period, children develop a permanent sense of self and object.

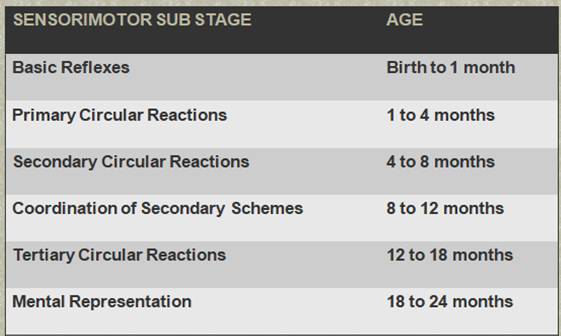

Piaget divided the sensorimotor stage into six sub stages:

|

• Object permanence: The understanding that objects continue to exist when they are out of sight. • Imitation: To copy actions and sounds. • Deferred imitation: the ability to remember and copy the behavior of models who are not immediately present. • “A” not “B” Phenomena: If an object is sequentially moved from one hidden place to another, the infant will search under the first cover ( also known as AB search error.

|

2. Preoperational stage

Piaget's second stage, the preoperational stage, starts when the child begins to learn to speak at age two and lasts up until the age of seven. During the Preoperational Stage of cognitive development, Piaget noted that children do not yet understand concrete logic and cannot mentally manipulate information. Children's increase in playing and pretending takes place in this stage. However, the child still has trouble seeing things from different points of view. The children's play is mainly categorized by symbolic play and manipulating symbols. Such play is demonstrated by the idea of checkers being snacks, pieces of paper being plates, and a box being a table. Their observation of symbols exemplifies the idea of play with the absence of the actual objects involved. By observing sequences of play, Piaget was able to demonstrate that, towards the end of the second year, a qualitatively new kind of psychological functioning occurs, known as the Preoperational Stage.

Following are the accomplishments of Pre-Operational Stage:

a. Semantic function. During this stage the child develops the ability to think using symbols and signs. Symbols represent something or someone else; for example, a doll may symbolize a baby, child or an adult. b. Egocentrism. This stage is characterized by egocentrism. Children believe that their way of thinking is the only way to think.

c. Decentering. A pre-operational child has difficulty in seeing more than one dimension or aspects of situation. It is called decentering.

d. Animism. Children tend to refer to inanimate objects as if they have life-like qualities and are capable of actions.

e. Seriation. They lack the ability of classification or grouping objects into categories. f. Conservation. It refers to the understanding that certain properties of an object remain the same despite a change in their appearance.

3. Concrete operational stage

During this stage, children begin to thinking logically about concrete events. They begin to understand the concept of conservation; that the amount of liquid in a short, wide cup is equal to that in a tall, skinny glass. Their thinking becomes more logical and organized, but still very concrete. Children begin using inductive logic, or reasoning from specific information to a general principle.

Children also become less egocentric and begin to think about how other people might think and feel. Kids in the concrete operational stage also begin to understand that their thoughts are unique to them and that not everyone else necessarily shares their thoughts, feelings, and opinions.

The achievements of this stage are:

· Conservation: The understanding that certain physical characteristics of objects remain the same even when their outward appearance changes.

· Hierarchical classification: Categorical thinking

· Seriation: The ability to arrange item along a quantitative dimension

· Spatial reasoning: Understanding of distance, direction and maps

4. Formal operational stage

The final stage is known as the formal operational stage (adolescence and into adulthood, roughly ages 11 to approximately 15–20): Intelligence is demonstrated through the logical use of symbols related to abstract concepts. This form of thought includes "assumptions that have no necessary relation to reality." At this point, the person is capable of hypothetical and deductive reasoning. During this time, people develop the ability to think about abstract concepts.

Piaget stated that "hypothetic-deductive reasoning" becomes important during the formal operational stage. This type of thinking involves hypothetical "what if" situations that are not always rooted in reality, i.e. counterfactual thinking. It is often required in science and mathematics.

· Abstract thought emerges during the formal operational stage. Children tend to think very concretely and specifically in earlier stages, and begin to consider possible outcomes and consequences of actions.

· Metacognition, the capacity for "thinking about thinking" that allows adolescents and adults to reason about their thought processes and monitor them.

· Problem-solving is demonstrated when children use trial and error to solve problems. The ability to systematically solve a problem in a logical and methodical way emerges.

Strengths of Piaget’s Theory

· Piaget's theory has been very influential, impacting psychology and education over the years while also being controversial.

· His theory is largely responsible for helping teachers, parents, and childcare workers to become fascinated observers of children's development

Classroom Implication of Piaget’s Theory

· Focus on the process of learning, rather than the end product of it.

· Using active methods that require rediscovering or reconstructing "truths."

· Using collaborative, as well as individual activities (so children can learn from each other).

· Devising situations that present useful problems, and create disequilibrium in the child.

· Evaluate the level of the child's development so suitable tasks can be set.

Limitations of Piaget’s Theory:

· The descriptions of stages are not valid.

· Piaget underestimated the abilities of young children

· Abstract directions and conservation of number task

· Piaget overestimated the abilities of older learners

· Think logically in the abstract

· Piaget’s work is context free and failed to adequately examine the influence of culture on development

Vygotsky Theory of Social Development

Vygotsky's theories stress the fundamental role of social interaction in the development of cognition (Vygotsky, 1978), as he believed strongly that community plays a central role in the process of "making meaning." Unlike Piaget's notion that childrens' development must necessarily precede their learning, Vygotsky argued, "learning is a necessary and universal aspect of the process of developing culturally organized, specifically human psychological function" (1978, p. 90). In other words, social learning tends to precede (i.e. come before) development.

No single principle (such as Piaget's equilibration) can account for development. Individual development cannot be understood without reference to the social and cultural context within which it is embedded. Higher mental processes in the individual have their origin in social processes

Vygotsky presented the social development theory -three major themes in vygotsky’s social development theory are that:-

1. Social Interaction: Development in a child appears first on a social level with others and then inside the child

2. The child learns from a more knowledgeable other, and

3. Zone proximal development ( learning occurs in a zone of proximal development between the learners ability to learn with the support of others and the ability to learn independently.

Social interaction

Vygotsky felt social learning anticipates development. He states: “Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological).” He believes that young children are curious and actively involved in their own learning and the discovery and development of new understandings.

Areas were social interaction can influence cognitive development…

* Engagement between the teacher and student

* Physical space and arrangement in learning environment

* Meaningful instruction in small or whole groups

* Scaffolding/Reciprocal teaching strategies

* Zone of Proximal Development

The More Knowledgeable Other (MKO)

Refers to anyone who has better understanding or higher ability level than the learner. Normally thought of as being a teacher, trainer, or older, adult, but MKO could also peers , a younger person, even computers.

Zone of Proximal Development

The zone of proximal development is the area of learning that a more knowledgeable other (MKO) assists the student in developing a higher level of learning. The goal is for the MKO to be less involved as the student develops the necessary skills.

Vygotsky describes it as “the distance between the actual development level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978).

The zone of proximal development (ZPD) contains two features :

1. Scaffolding

Vygotsky defined scaffolding instruction as the “role of teachers and others in supporting the learners development and providing support structures to get to that next stage or level” (Raymond, 2000). Teachers provide scaffolds so that the learner can accomplish certain tasks they would otherwise not be able to accomplish on their own. The goal of the educator is for the student to become an independent learner and problem solver.

2. Reciprocal Teaching

Reciprocal Teaching is used to improve a student’s ability to learn from text through the practice of four skills: summarizing, clarifying, questioning, and predicting.

Biological & Cultural Development

Vygotsky (1978) states: “Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later on the individual level; first, between people and then inside the child. This applies equally to voluntary attention, to logical memory, and to the formation of concepts. All the higher functions originate as actual relationships between individuals.”

Simplified: community plays a central role in the process of “making meaning”

Language

Language plays a central role in mental development. It is the main means by which adults transmit information to children. Language itself becomes a very powerful tool of intellectual adaptation. It provides means for expressing ideas and asking questions, the categories and concepts for thinking.

PRIVATE SPEECH- children’s self-talk, which guides their thinking and action. Eventually these verbalizations are internalized as silent inner speech.

Classroom Implication of Vygotsky’s Theory

· He suggests that teachers need to do more than just arrange the environment so that students can discover on their own .

· One major aspect of teaching in either situation is assisted learning.

· ASSISTED LEARNING- requires scaffolding –giving information ,prompts, reminders, and encouragement at the right time and in the right amounts, and then gradually allowing the students to do more and more on their own.

· Break the task down into manageable steps.

· Model and define the expectations of the activity.

· Use props to illustrate each of the four skills to be practiced: summarizing, clarifying, questioning, and predicting.

· Have students buddy read and practicing using the reciprocal strategies.

Piaget Vs. Vygotsky

Albert Bandura Theory of Social Learning

Bandura’s Social Learning Theory posits that people learn from one another, via observation, imitation, and modeling. The theory has often been called a bridge between behaviorist and cognitive learning theories because it encompasses attention, memory, and motivation.

The Theory

It was Albert Bandura‘s intention to explain how children learn in social environments by observing and then imitating the behaviour of others. In essence, be believed that learning could not be fully explained simply through reinforcement, but that the presence of others was also an influence. He noticed that the consequences of an observed behavior often determined whether or not children adopted the behavior themselves.

Through a series of experiments, he watched children as they observed adults attacking Bobo Dolls. When hit, the dolls fell over and then bounced back up again. Then children were then let loose, and imitated the aggressive behavior of the adults. However, when they observed adults acting aggressively and then being punished, Bandura noted that the children were less willing to imitate the aggressive behavior themselves.

Reciprocal determinism

Bandura believed in “reciprocal determinism”, that is, the world and a person’s behavior cause each other, while behaviorism essentially states that one’s environment causes one’s behavior[2], Bandura, who was studying adolescent aggression, found this too simplistic, and so in addition he suggested that behavior causes environment as well[3]. Later, Bandura soon considered personality as an interaction between three components: the environment, behavior, and one’s psychological processes (one’s ability to entertain images in minds and language).

Social learning theory has sometimes been called a bridge between behaviorist and cognitive learning theories because it encompasses attention, memory, and motivation. The theory is related to Vygotsky’s Social Development Theory and Lave’s Situated Learning, which also emphasize the importance of social learning.

Bandura’s 4 Pinciples Of Social Learning

From his research Bandura formulated four principles of social learning.

1. Attention: We cannot learn if we are not focused on the task. If we see something as being novel or different in some way, we are more likely to make it the focus of their attention. Social contexts help to reinforce these perceptions.

2. Retention: We learn by internalizing information in our memories. We recall that information later when we are required to respond to a situation that is similar the situation within which we first learned the information.

3. Reproduction: We reproduce previously learned information (behavior, skills, knowledge) when required. However, practice through mental and physical rehearsal often improves our responses.

4. Motivation: We need to be motivated to do anything. Often that motivation originates from our observation of someone else being rewarded or punished for something they have done or said. This usually motivates us later to do, or avoid doing, the same thing.

How it can be applied to education

Social modelling is a very powerful method of education. If children see positive consequences from a particular type of behaviour, they are more likely to repeat that behaviour themselves. Conversely, if negative consequences are the result, they are less likely to perform that behaviour. Novel and unique contexts often capture students’ attention, and can stand out in the memory.

Students are more motivated to pay attention if they see others around them also paying attention. Another less obvious application of this theory is to encourage students to develop their individual self efficacy through confidence building and constructive feedback, a concept that is rooted in social learning theory.

2.2 Psychological Theory ( Erickson)

Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development

Erik Erikson –a psychologist –theorized that there several stages of psychosocial development. His theory identifies eight stages through which a healthily developing human should pass from infancy to late adulthood. In each stage, the person confronts, and hopefully masters, new challenges. Each stage builds upon the successful completion of earlier stages. The challenges of stages not successfully completed may be expected to reappear as problems in the future. Erikson's stage theory characterizes an individual advancing through the eight life stages as a function of negotiating his or her biological forces and sociocultural forces. Each stage is characterized by a psychosocial crisis of these two conflicting forces .

Psychosocial refers to the interaction between the individuals psychological development and his/her social environment

* Feeling of self worth.

* Satisfaction with roles in life.

* Positive relationship with others.

Personality of an individual develops through a series of stages also known as life crisis, spread over the entire life span. Each crisis must be resolved successfully for satisfaction in later life. Erikson gave emphasis on the development of ego identity. Ego identity is the conscious sense of self that we develop through social interaction. It is constantly changing due to new experiences and information we acquire in our daily interactions with others. Erikson also believed that a sense of competence motivates behavior and actions

Each stage is concerned with becoming competent in an area of life. If the stage is handled well, the person will fell a sense of mastery, which is referred as ego strength. If the stage is managed poorly, the person will develop a sense of inadequacy.

1. Stage 1 - Trust vs. Mistrust

The first stage of Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development occurs between birth and one year of age and is the most fundamental stage in life. Because an infant is utterly dependent, the development of trust is based on the dependability and quality of the child’s caregivers. If a child successfully develops trust, he or she will feel safe and secure in the world. Caregivers who are inconsistent, emotionally unavailable, or rejecting contribute to feelings of mistrust in the children they care for. Failure to develop trust will result in fear and a belief that the world is inconsistent and unpredictable.

2. Stage 2 - Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt

The second stage of Erikson's theory of psychosocial development takes place during early childhood and is focused on children developing a greater sense of personal control. Like Freud, Erikson believed that toilet training was a vital part of this process. However, Erikson's reasoning was quite different then that of Freud's. Erikson believe that learning to control one’s body functions leads to a feeling of control and a sense of independence. Other important events include gaining more control over food choices, toy preferences, and clothing selection. Children who successfully complete this stage feel secure and confident, while those who do not are left with a sense of inadequacy and self-doubt.

3. Stage 3 - Initiative vs. Guilt

During the preschool years, children begin to assert their power and control over the world through directing play and other social interaction. Children who are successful at this stage feel capable and able to lead others. Those who fail to acquire these skills are left with a sense of guilt, self-doubt and lack of initiative.

4. Stage 4 - Industry vs. Inferiority

This stage covers the early school years from approximately age 5 to 11. Through social interactions, children begin to develop a sense of pride in their accomplishments and abilities. Children who are encouraged and commended by parents and teachers develop a feeling of competence and belief in their skills. Those who receive little or no encouragement from parents, teachers, or peers will doubt their ability to be successful.

5. Stage 5 - Identity vs. Confusion

During adolescence, children are exploring their independence and developing a sense of self. Those who receive proper encouragement and reinforcement through personal exploration will emerge from this stage with a strong sense of self and a feeling of independence and control. Those who remain unsure of their beliefs and desires will insecure and confused about themselves and the future.

6. Stage 6 - Intimacy vs. Isolation

This stage covers the period of early adulthood when people are exploring personal relationships. Erikson believed it was vital that people develop close, committed relationships with other people. Those who are successful at this step will develop relationships that are committed and secure. Remember that each step builds on skills learned in previous steps. Erikson believed that a strong sense of personal identity was important to developing intimate relationships. Studies have demonstrated that those with a poor sense of self tend to have less committed relationships and are more likely to suffer emotional isolation, loneliness, and depression.

7. Stage 7 - Generativity vs. Stagnation

During adulthood, we continue to build our lives, focusing on our career and family. Those who are successful during this phase will feel that they are contributing to the world by being active in their home and community. Those who fail to attain this skill will feel unproductive and uninvolved in the world.

8. Stage 8 - Integrity vs. Despair

This phase occurs during old age and is focused on reflecting back on life. Those who are unsuccessful during this phase will feel that their life has been wasted and will experience many regrets. The individual will be left with feelings of bitterness and despair. Those who feel proud of their accomplishments will feel a sense of integrity. Successfully completing this phase means looking back with few regrets and a general feeling of satisfaction. These individuals will attain wisdom, even when confronting death

2.3 Mortality: (Kohlberg and Gilligan)

Kohlberg had applied Piaget's theory to the development of moral thinking. Borrowing from Piaget's "preoperational/concrete/formal" distinctions Kohlberg came up with the stage theory you see here.

1. The pre-conventional moral stage, says Kohlberg, is based on the cognitive abilities of a person in Piaget's concrete operational stage. Moral decisions are egocentric (based on me) and concrete. So you can see how reward and punishment are the typical bases of reasoning in this stage.

2. The conventional stage is based on the children's ability to "decenter" their moral universe and take the moral perspective of their parents and other important members of society into account.

3. The post-conventional stage is based on the adult's ability to base morality on the logic of principled decision making based on standards that are thought to be universalizable and not dependent on culture. Kohlberg's system was based on extensive research he and his students did with interviews in which they asked children and adults to give the reasons they had for moral decisions Kohlberg presented them with. So his stages and ages do not correspond exactly from Piaget, but you can see a tantalizing similarity

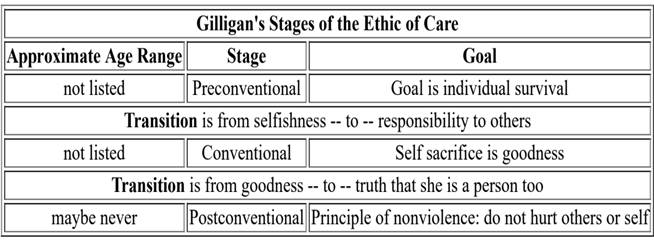

Now we finally get to Gilligan. As a student of Kohlberg's, Gilligan was taken by the stage theory approach to understanding moral reasoning. But she disagreed with her mentor's assessment of the content of the moral system within which people developed. If you look at the table of Kohlberg's stages, you can see the question being answered in the third column is one of justice the fourth stage gives this away with talk about duty and guilt. "What are the rules of the game?" seems to be the issue at hand. From her careful interviews with women making momentous decisions in their lives, Gilligan concluded that these women were thinking more about the caring thing to do rather than the thing the rules allowed. So she thought Kohlberg was all wet, at least with regard to women's development in moral thinking.

What set her off in thinking this was the fact that in some of Kohlberg's investigations, women turned out to score lower less developed than did men. Were women really moral midgets? Gilligan did not think so. In taking this stand, she was going against the current of a great deal of psychological opinion. Our friend Freud thought women's moral sense was stunted because they stayed attached to their mothers. Another great developmental theorist, Erik Erickson, thought the tasks of development were separation from mother and the family. If women did not succeed in this scale, then they were obviously deficient.

Gilligan's reply was to assert that women were not inferior in their personal or moral development, but that they were different. They developed in a way that focused on connections among people (rather than separation) and with an ethic of care for those people (rather than an ethic of justice). Gilligan lays out in this groundbreaking book this alternative theory.

Thus Gilligan produces her own stage theory of moral development for women. Like Kohlberg's, it has three major divisions: preconventional, conventional, and post conventional. But for Gilligan, the transitions between the stages are fueled by changes in the sense of self rather than in changes in cognitive capability. Remember that Kohlberg's approach is based on Piaget's cognitive developmental model. Gilligan's is based instead on a modified version of Freud's approach to ego development. Thus Gilligan is combining Freud (or at least a Freudian theme) with Kohlberg & Piaget.

Kohlberg and Gilligan: The major differences

1. For Gilligan the moral self is radically situated and particularized. It is "thick" rather than "thin," defined by its historical connections and relationships. The moral agent does not attempt to abstract from this particularized self, to achieve, as Kohlberg advocates, a totally impersonal standpoint defining the "moral point of view." For Gilligan, care morality is about the particular agent's caring for and about the particular friend or child with whom she has come to have this particular relationship. Morality is not (only) about how the impersonal "one" is meant to act toward the impersonal "other."

2. For Gilligan, not only is the self radically particularized, but so is the other, the person toward whom one is acting and with whom one stands in some relationship. The moral agent must understand the other person as the specific individual that he or she is, not merely as someone instantiating general moral categories such as friend or person in need. Moral action which fails to take account of this particularity is faulty and defective. While Kohlberg does not and need not deny that there is an irreducible particularity in our affective relationships with others, he sees this particularity only as a matter of personal attitude and affection, not relevant to morality itself. For him, as, implicitly, for a good deal of current moral philosophy, the moral significance of persons as the objects of moral concern is solely as bearers of morally significant but entirely general and repeatable characteristics.

3. Gilligan shares with Iris Murdoch (The Sovereignty of Good) the view that achieving knowledge of the particular other person toward whom one acts is an often complex and difficult moral task and one which draws on specifically moral capacities.8 Understanding the needs, interests, and welfare of another person, and understanding the relationship between oneself and that other requires a stance toward that person informed by care, love, empathy, compassion, and emotional sensitivity. Kohlberg's view follows a good deal of current moral philosophy in ignoring this dimension of moral understanding, thus implying that knowledge of individual others is a straightforwardly empirical matter requiring no particular moral stance toward the person.

4. Gilligan portrays the moral agent as approaching the world of action bound by ties and relationships (friend, colleague, parent, child) which confront her as, at least to some extent, givens. These relationships, while subject to change, are not wholly of the agent's own making and thus cannot be pictured on a totally voluntarist or contractual model. In contrast to Kohlberg's conception, the moral agent is not conceived of as radically autonomous (though this is not to deny that there exists a less individualistic, less foundational, and less morality-generating sense of autonomy which does accord with Gilligan's conception of moral agency).

5. For Kohlberg the mode of reasoning which generates principles governing right action involves formal rationality alone. Emotions play at most a remotely secondary role in both the derivation and motivation for moral action. For Gilligan, by contrast, morality necessarily involves an intertwining of emotion, cognition, and action, not readily separable. Knowing what to do involves knowing others and being connected in ways involving both emotion and cognition. Caring action expresses emotion and understanding.

6. For Kohlberg principles of right action are universalistic, applicable to all. Gilligan rejects the notion that an action appropriate to a given individual is necessarily (or needs to be regarded by the agent as) universal, or generalizable to others. And thus she at least implicitly rejects, in favor of a wider notion of "appropriate response," a conception of "right action" which carries this universalistic implication.

7. For Gilligan morality is founded in a sense of concrete connection and direct response between persons, a direct sense of connection which exists prior to moral beliefs about what is right or wrong or which principles to accept. Moral action is meant to express and to sustain those connections to particular other people. For Kohlberg the ultimate moral concern is with morality itself-with morally right action and principle; moral responsiveness to others is mediated by adherence to principle.

2.4 Ecological Theory ( Bronfrenbrenner)

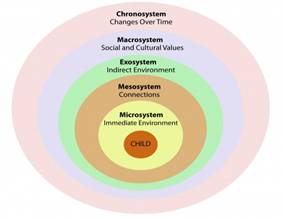

American psychologist, Urie Bronfenbrenner, formulated the Ecological Systems Theory to explain how the inherent qualities of a child and the characteristics of the external environment which the child finds himself in interact to influence how the child will grow and develop. Through his theory, Bronfenbrenner stressed the importance of studying a child in the context of his multiple environments, also known as ecological systems in the attempt to understand his individual development.

A child finds himself simultaneously enmeshed in different ecosystems, from the most intimate home ecological system moving outward to the larger school system and the most expansive system which is society and culture. Each of these systems inevitably interact with and influence each other and every aspect of the child’s life.

1. The Microsystem

Consisting of the child’s most immediate environment (physically, socially and psychologically), this core entity stands as the child’s venue for initially learning about the world. As the child’s most intimate learning setting, it offers him or her a reference point of the world. It may provide the nurturing centerpiece for the child or become a haunting set of memories of one’s earliest encounters with violence. The real power in this initial set of interrelations with family for the child is what they experience in terms of developing trust and mutuality with their significant people. The family is clearly the child’s early microsystem for learning how to live. The caring relations between child and parents (and many other caregivers) can help to influence a healthy personality. For example, the attachment behaviors of parents offer children their first trust-building experience.

2. The Exosystem

The close, intimate system of our relations within families creates our buffer and ‘‘nest’’ for being with each other. However, we all live in systems psychologically and not physically; these are exosystems. For example, parents may physically be at work but psychologically they are very present in the child-care center their child attends. Likewise, the child in first grade ‘‘goes to work’’ with the parents in the sense that they wonder about and seek experiences with ‘‘the work of the family’’ they never really physically experience. Exosystems are the contexts we experience vicariously and yet they have a direct impact on us. They can be empowering (as a high quality child-care program is for the entire family) or they can be degrading (as excessive stress at work is on the total family ecology). In so many cases exosystems bring about stress in families because we do not attend to them as we should. Our absence from a system makes it no less powerful in our lives. For example, many children realize the stress of their parent’s workplaces without ever physically being in these places. We all need to seek to be involved in our exosystems, encouraging more family-friendly practices.

3. The Macrosystem

The larger systems of cultural beliefs, societal values, political trends, and ‘‘community happenings’’ act as a powerful source of energy in our lives. The macrosystems we live in influence what, how, when and where we carry out our relations (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). For example, a program like Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) may positively impact a young mother through health care, vitamins, and other educational resources. It may empower her life so that she in turn, is more affective and caring with her newborn (Swick, 2004). In a sense, the macrosytems that surround us help us to hold together the many threads of our lives. Without an umbrella of beliefs, services, and supports for families, children and their parents are open to great harm and deterioration.

4. Mesosytems

The real power of mesosystems is that they help to connect two or more systems in which child, parent and family live. They help to move us beyond the dyad or two-party relation. So mesosystems are or should permeate our lives in every dimension. For example, the friend at church who links you up to ‘‘parent night out’’ and then in turn, watches your baby while you attend an evening adult education course is indeed a powerful mesosytem agent. As Mary Pipher (1996) cautions, ‘‘community’’ must become a concrete reality for young children and their parents. There must be loving adults beyond the parents who engage in caring ways with our children. In the ritualistic symbols of many native American people there is a thing called tiospaye which means to be ‘‘in community with each other’’. This is what mesosystems are about—being in relation with each other in ever expanding circles of triads and even more expansive relations. Without strong mesosystems families tend to fall into chaos.

5. Chronosystems

Framing all of the dynamics of families is the historical context as it occurs within the different systems (Bronfenbrenner, 1989). For example, the ‘‘history’’ of relationships in families may explain more about parent-child relations than is evident in existing dynamics (Ford & Lerner, 1992). Another example is the powerful influence that historical influences in the macrosystem have on how families can respond to different stressors. Bronfenbrenner (1979) suggests strongly that, in many cases, families respond to different stressors within the societal parameters existent in their lives. During the Great Depression of the 1930’s many families simply were ecstatic to have food and did not have the luxury to worry about the nutritional value of the food they had on the table. Yet they were concerned but the macrosystem elements present in their lives that established the limited vision they could have regarding these issues. All of the systems influence family functioning, they are dynamic and interactive—fostering a framework for parents and children. Our understanding of the ‘‘contexts’’ in which family stressors occur can help us in being effective helpers.

Implications for practice

Bronfenbrenner sees the instability and unpredictability of family life we’ve let our economy create as the most destructive force to a child’s development (Addison, 1992). Children do not have the constant mutual interaction with important adults that is necessary for development. According to the ecological theory, if the relationships in the immediate micro system break down, the child will not have the tools to explore other parts of his environment. Children looking for the affirmations that should be present in the child/parent (or child/other important adult) relationship look for attention in inappropriate places. These deficiencies show themselves especially in adolescence as anti-social behavior, lack of self-discipline, and inability to provide self-direction (Addison, 1992).

This theory has dire implications for the practice of teaching. Knowing about the breakdown occurring within children’s homes, is it possible for our educational system to make up for these deficiencies? It seems now that it is necessary for schools and teachers to provide stable, long-term relationships. Yet, Bronfenbrenner believes that the primary relationship needs to be with someone who can provide a sense of caring that is meant to last a lifetime. This relationship must be fostered by a person or people within the immediate sphere of the child’s influence. Schools and teachers fulfill an important secondary role, but cannot provide the complexity of interaction that can be provided by primary adults. For the educational community to attempt a primary role is to help our society continue its denial of the real issue. The problems students and families face are caused by the conflict between the workplace and family life – not between families and schools. Schools and teachers should work to support the primary relationship and to create an environment that welcomes and nurtures families. We can do this while we work to realize Bronfenbrenner’s ideal of the creation of public policy that eases the work/family conflict. It is in the best interest of our entire society to lobby for political and economic policies that support the importance of parent’s roles in their children’s development. Bronfenbrenner would also agree that we should foster societal attitudes that value work done on behalf of children at all levels: parents, teachers, extended family, mentors, work supervisors, legislators.