3.1 Definition, Types and Characteristics

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are complex neurological disorders that have a lifelong effect on the development of various abilities and skills. Helping students to achieve to their highest potential requires both an understanding of ASD and its characteristics, and the elements of successful program planning required to address them.

The term “spectrum” is used to recognize a range of disorders that include a continuum of developmental severity. The symptoms of ASD can range from mild to severe impairments in several areas of development. Many professionals in the medical, educational, and vocational fields are still discovering how ASD affects people and how to work effectively with individuals with ASD.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

• A developmental disability affecting verbal and non-verbal communication and social interaction,(Age<3).

• Engagement in repetitive activities and stereotyped movements, resistance to environmental change or change in daily routines, and unusual responses to sensory experiences.

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA)

• Autism is defined as a developmental disability significantly affecting verbal and non- verbal communication and social interaction, generally (< age 3), which adversely affects a child's educational performance

Classification

The most recent and updated version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version 5 (DSM -5) of American Psychiatric Association has just a single category for the diagnosis of an autistic disorder – autism spectrum disorders, which include the following disorders that were previously discussed separately:

Autism or Autistic Disorder: Children who seem to have met most of the rigid criteria of a diagnosis of Autism are said to have Autism or Autistic Disorder. They have moderate to severe impairments in Social and Language skills, possess Repetitive Behaviors and Restricted Interests. Often the children and individuals with Autistic Disorder also have mental retardation and seizures.

Asperger’s Syndrome: Asperger Syndrome: AS, is the mildest form of Autism. It is found to have affected boys three times more in comparison with girls.

The most common symptoms of Asperger Syndrome are the children affected become excessively interested in a single subject or topic. They tend to find out and learn everything about their preferred subject and talk about it all the time. As compared with other form of Autism, children with Asperger have extremely good vocabulary however their social skills are markedly impaired and they are often awkward and uncoordinated.

It is also found that the children with Asperger’s Syndrome very often have normal or above normal IQ (Intelligence Quotient). As a result, many doctors address it as High-Functioning Autism. As children with AS enter into Childhood, they are at a high risk of developing Anxiety and Depression.

PDD-NOS (Pervasive Development Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified): PDD-NOS is a little complex syndrome to diagnose amongst children on the Autism Spectrum. Commonly children & individuals whose behavioral symptoms are more severe than Asperger’s Syndrome but less severe than Autistic Disorder are diagnosed as PDD-NOS.

No two children/individuals with PDD-NOS exhibit similar symptoms. This makes generalizing the disorder rather more complex. Commonly, children with PDD-NOS exhibit following symptoms:

Impaired social communication/interaction (similar to Autistic Disorder)

Better language/communication skills as compared to children with Autistic Disorder however these skills are not as good as of children with Asperger’s Syndrome

Lesser sensory dysfunction as a result fewer repetitive behaviors

Rett Syndrome : Rett Syndrome is severe form of Autism and it mostly occurs in girls. It is mostly caused by a genetic mutation wherein the mutation occurs randomly and has no inherited significance. It is a rare syndrome affecting about one in 10,000-15,000 girls.

In this syndrome, girls aging between 6 to 18 months of age regress marginally and lose linguistic and social skills. They habitually wring hands and develop coordination problems. Head growth slows down significantly and by the age of two their head appears to be far below normal. The treatment of Rett Syndrome focuses mostly on physical therapy and speech therapy to improve function.

Child Disintegrative Disorder : It is the least common and most severe form of Autism Spectrum Disorder. In CDD, the child rapidly loses multiple areas of function between the ages of 2 to 4 years of age. This regression takes place in social skills, linguistic skills as well as in intellectual abilities.

Very often the child develops a seizure disorder. The children with CDD – Childhood Disintegrative Disorder are severely impaired and don’t recover their lost function.

The number of children affecting CDD is lesser than 2 children per 100,000 children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Boys are more commonly affected by CDD than girls.

Causes of ASD

There are several theories about the cause or causes of ASD. Researchers are exploring various explanations but, to date, no definitive answers or specific causes have been linked scientifically to the onset of ASD. Research suggests that individuals with ASD experience biological or neurological differences in the brain.

In many families, there appears to be a pattern of ASD-related disabilities, which suggests that ASD is an inherited genetic disorder. Current research studies show that certain classes of genes may be involved or work in combination to cause ASD. There appear to be many different forms of genetic susceptibility but, to date, no single gene has been directly related to ASD (Autism Genome Project Consortium, 2007). Ongoing research is being done to further investigate the cause of ASD.

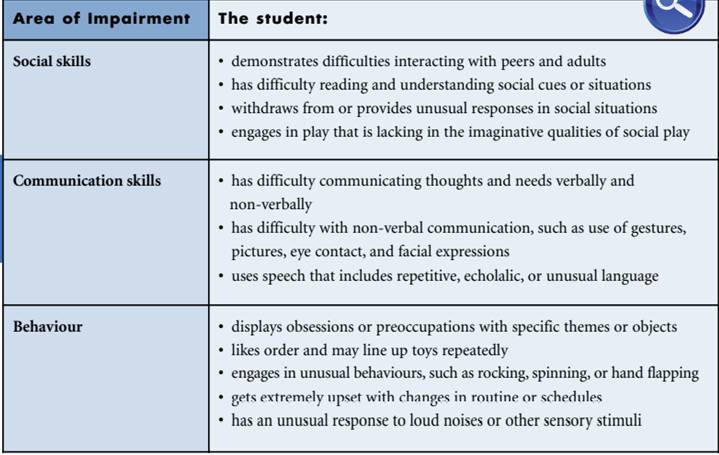

Characteristics

Qualitative Impairment in Social Relationships:

· Children/individuals with Autism have limited or non-existent interest in, or desire to Socialise with others. Children with attention related disorders may have extremely poor skills but there is no lack of desire to relate to others.

· Mothers may notice in the early weeks of life that their baby seems ‘different’ and shows little interest in them, may resist being cuddled or smiling. Infant interactive games such as ‘peek-a-boo’ and nursery rhymes are ignored.

· The toddler may not watch other children and may not run up to play with them. Whilst the shy child may hide or refuse to join a group, the autistic child seems unaware of the group and doesn’t respond to it.

· At times, autistic children are often termed as being socially “aloof”, will often ignore other people, and may seem unable to distinguish between people and objects.

· Play is typically solitary, and often repetitive or restricted to a single type of object or activity.

· The child cannot imitate, and may not wave or smile responsively.

· Interactions initiated by the child serve only to achieve the child’s immediate wants and needs, rather than to make friends or play.

· The older child may be unable to show empathy or understanding of other point-of-view or experiences, and will neither make nor desire friendships.

Extremely Rigid Pattern of Behaviour :

· Almost every individual with Autism finds it extremely difficult to cope with the demands of a changing environment or set of expectations, or in generating rapid and appropriate responses to new experiences.

· Once they have found a comforting or a pleasurable experience they will tend to repeat it endlessly. Thence their interests seem narrow and their behavior lacks flexibility or variation.

Non-Diagnostic Behaviours

· An excellent photographic memory for places or things is often described in autistic children.

· Unusual responses to sensory stimulation such as extreme responses to sounds – children may be fascinated with particular sounds and distressed by others.

· Autistic children are frequently fascinated by bright or flashing lights and may spend hours watching rotating ceiling fan or other rotating objects. They may seem obsessed by spinning wheel of a toy car, mirrors and revolving parts of machinery.

· Autistic children have described major difficulty in visual perception so that they have difficulty seeing objects as a whole. An adult autistic explained that “she had never seen a tree, just thousands of individual leaves.”

· This type of visual perceptual difficulty can compound the difficulties experienced by autistic people in complex social situations and clearly interferes with much conceptual learning.

· Hyperlexia is characterized by a preoccupation with print noted before the age of three years. In some cases hyperlexic children can read what they see, although usually without understanding.

· Autistic children seem unduly sensitive to pressure on the skin – they may compulsively undress, taking tight garments off with obvious relief, or conversely they may seek and enjoy pressure on skin and joints.

· They may show abnormal tactile response decrement – whilst most people do not feel their tight underwear or socks half a minute after they have put them on, the autistic person may continue to be aware of such sensations for hours. The children may spend hours in such tactile exercises as playing with a piece of silk, sandpaper, velvet or wood.

Language and Imagination

• Language has both verbal as well as non-verbal components. Both are impaired in Autistic Spectrum Disorder.

• Impaired non-verbal skills are manifest as poor or interpersonal synchrony, poor eye contact, an “empty gaze” or even a discomforting, piercing stare.

• Inappropriate body language such as unawareness of personal space – standing or sitting too close for conversational comfort.

• Absent or inappropriate gesture or smiling may include smiling which may seem unrelated to current experience.

• Individuals with Asperger Disorder may reach basic language milestones normally but their use of language is abnormal. They are unable to maintain a conversation, and understand the meaning of words only in their most literal sense, so that often unable to understand metaphor, sarcasm, puns or humor. Their speech is monotonous and like their facial expression, conveys little or no emotion.

• Expressive language is not simply delayed in autism, it seems to follow an abnormal or deviant developmental path. The child may repeat words or phrases just heard but not understood (Immediate Echolalia) or may suddenly repeat a sentence heard a day or two before (Delayed Echolalia).

• A severe deficit in Pragmatics can be identified Autistic people even if their expressive language is otherwise perfect or in many cases of Asperger Disorder.

3.2 Tools and Areas of Assessment

Areas of assessment

Screening and Diagnostic Assessments

Screening and diagnostic assessments for autism are usually made after detailed interviews with the family members, and after observations of and interactions with the individual with autism. The specific protocol used will depend on the age, skills and interests of the individual, as well as his or her background.

• Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS)

• The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)

• CARS (Childhood Autism Rating Scale)

• GARS (Gilliam Autism Rating Scale)

• SCQ (Social Communication Questionnaire)

• SRS (Social Responsiveness Scale)

• MCHAT-R (Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers)

• ISAA (Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism)

3.3 Instructional Approaches

The National Research Council (2001) found that no one specific method or intervention is effective for all individuals with ASD and that integrating a variety of approaches leads to the development of programs that promote the best outcomes for students. Integrating a variety of approaches leads to the development of programs that promote the best outcomes for students.

Differentiated Instruction: As recommended in Education for All, teachers can effectively respond to a learner’s needs and strengths through the use of differentiated instruction. Through this approach, the specific skills or difficulties of students with ASD can be addressed by employing a variety of methods to differentiate (or vary) the following:

· The content: The depth or breadth of the information or skills to be taught.

· The processes: The instructional approaches used with the student, as well as the materials used to deliver or illustrate the content.

· The products of the learning situation: What the end product will be or look like. This product may be tangible (a worksheet, project, composition), a skill that has been acquired, or knowledge that has been gained.

Visual Supports: The use of visual supports is one of the most widely recommended strategies for teaching students with ASD, as they usually process visual information more efficiently and effectively than information that is presented verbally. Some students may require extra time to process verbal language and understand the message. Speech is transient: once information or instructions have been spoken, the message is no longer available and students must recall the information from memory.

Structured Learning Environment: All children function better in a predictable environment. Students with ASD require a structured learning environment to know what is expected of them in specific situations, to assist them in anticipating what comes next, and to learn and generalize a variety of skills. Rules and expectations should be clear and consistent and include specific information regarding the expectations for appropriate behaviour.

Assistive Technology: In Education for All, assistive technology is defined as any technology that allows one to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of an individual with special learning needs. Its applications and adaptations can help open doors to previously inaccessible learning opportunities for many children with special needs. Assistive technology includes highly technical (commonly referred to as “high-tech”) computerized devices such as speech generating software, as well as less technical (“low-tech”) resources such as visual supports. Technology can be used by students to provide alternative methods to access information, demonstrate and reinforce learning, and interact with others. It can also be used by adults as a tool to support the teaching and learning process.

Sensory Considerations: Students with ASD vary in their sensitivity and tolerance to sensory stimulation in the environment. It is important to be aware of the sensory preferences or sensitivities of a student and to determine possible elements in the environment that might have an impact on a student’s learning and level of anxiety. Some students are very (“hyper-”) sensitive in one or more sensory areas and may be more comfortable in environments with reduced levels of sensory stimulation. Other individuals are under (“hypo-”) sensitive and seek enhanced sensory experience. For example, some students become anxious or upset because of an extreme sensitivity to certain sounds or have a difficulty processing more than one sense at a time. Other students seek additional sensory experiences in order to become or maintain calm.

Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication handicapped Children Method (TEACCH) emphasizes on using skills that children already possess to enable them to become independent. Organizing the physical environment, developing schedules and work systems, making expectations clear and explicit and visual materials are effective in developing skills and allowing people with autism to be independent of direct adult prompting.

Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) emphasizes on one-to-one sessions in discrete trial (DTT) format to develop cognitive, social, behavioral, fine motor, play, social and self help skills. The technique involves structured presentation of tasks from most simple to more complex, breaking them down into small sub-skills and teaching each sub-skill, intensely, one at a time. It involves repeated practices with prompting and fading of prompts to ensure success. It uses rewards or reinforcement to help shape and maintain desired behaviours and skills.

Pivotal Response Treatment (PRT): (ABA-based) PRT is a child-directed intervention that focuses on critical, or “pivotal,” behaviors that affect a wide range of behaviors. The primary pivotal behaviors are motivation and child’s initiations of communications with others. The goal of PRT is to produce positive changes in the pivotal behaviors, leading to improvement in communication, play and social behaviors and the child’s ability to monitor his own behavior. Child-directed intervention

Verbal Behavior Analysis (VBA) is an addition to ABA and is also based on breaking down and teaching language in functional units unlike the teaching of language based on grammar. In addition to teaching at the table top, teaching in (and with) the natural environment (NET) is important.

Picture Exchange Communication Systems (PECS) is built on the fact that non-verbal children with autism may attempt to spontaneously use objects to communicate. People with autism tend to be visual learners and visual means of communication can help them to understand and use the process of communication. PECS aims to teach spontaneous social-communication skills by means of symbols or pictures and teaching relies on behavioural principles, particularly reinforcement techniques. Behavioural strategies are employed to teach the person to use functional communicative behaviours to request desired objects. The requesting behaviour is reinforced by the receipt of the desired item.

Floortime, or Difference Relationship Model (DIR): The premise of Floortime is that an adult can help a child expand his circles of communication by meeting him at his developmental level and building on his strengths.Therapy is often incorporated into play activities – on the floor – and focuses on developing interest in the world, communication and emotional thinking by following the child’s lead.

Relationship Development Intervention (RDI): RDI seeks to improve the individual’s long-term quality of life by helping him improve social skills, adaptability and self-awareness through a systematic approach to building emotional, social and relational skills.

Social Communication/Emotional Regulation/Transactional Support (SCERTS): SCERTS uses practices from other approaches (PRT, TEACCH, Floortime and RDI), and promotes childinitiated communication in everyday activities and the ability to learn and spontaneously apply functional and relevant skills in a variety of settings and with a variety of partners. The SCERTS model favors having children learn with and from peers who provide good social and language models in inclusive settings as much as possible

3.4 Teaching Methods

When selecting teaching strategies, we are all aware that ‘one size fits all’ does not apply. It is important to acknowledge the individuality of each child. But there is another aspect beyond this that must be kept in mind when teaching children with autism.

Autism is a population that takes a uniquely different developmental path. While each child has his own specific style, a large number of children with autism have certain unique commonalities. These, in addition to their uneven patterns of strengths and weaknesses, are some unique learning characteristics that must be considered for their educational implications.

Generalisation: The ability to apply a skill in different situations is known as generalisation. Opportunities to generalise a skill learnt across situations, time and people must be given.

Concrete to abstract: Due to difficulties with imagination children with autism may find understanding of abstract concepts difficult. Because they focus concretely they often have difficulty with remembering the precise order of tasks. Here again visuals help. In addition, while teaching always starts with concrete objects and then moves to abstract concepts. Learning needs to be experiential and related to real life situations.

Rote learners: Children with autism have excellent rote memory and they may use this to compensate for their difficulties in comprehension. It is therefore imperative to work on language skills.

Literal understanding: As children with autism are literal interpreters it is essential to be clear and concrete in communication. It is best to avoid irony, sarcasm and metaphors. Children with autism may have difficulty with shared attention tasks which involves understanding what another person may be thinking. This is a skill which is vital in any teaching situation and highlights one of the main areas of learning difficulty in people with autism.

Reading: Many students with ASD have strong visual skills and are often more successful in learning to read through a whole word sight recognition approach than through a more traditional phonics program. Whole words that are meaningful are usually easier for students to learn to read than words for which students have no basis of experience or knowledge. In the beginning stages of learning to read, it is critical to enable students to develop a sense of confidence.

While knowing the alphabet and knowing the sound symbol associations are usually regarded as prerequisite skills for learning to read, many students with ASD often have difficulty acquiring these prerequisite skills. Some students are able to recite alphabet letters and letter sounds by rote, but may be unable to apply this to decoding words in a fluent manner. The rate of reading fluency will affect a student’s ability to comprehend the message of the words. If a student needs to give more cognitive attention to a difficult decoding process, then it is likely that the student’s understanding of what the words are saying will decrease.

Some students may be better able to understand and learn the phonetic components of words after they have learned to read them through a whole word sight recognition approach, working backwards within a top-down framework from the whole to the parts. It is important to consider that, although some students may be unable to manipulate the symbolic representations of sounds, they may still be able to recognize and comprehend words and acquire skills in phonics.

As the student acquires more words, it is essential to provide activities in which these words are used in meaningful contexts. Ongoing practice in sentence construction enables the student to understand how words are organized to express thoughts and needs, as well as how pronouns, articles, and prepositions are used in context. Daily practice in sentence construction provides students with the opportunity to develop an understanding of grammar and to learn a framework for using language. This practice also reinforces that repetition and rehearsal of language construction are ongoing expectations of daily task performance.

Writing: While some students with ASD are proficient in printing and handwriting, many others have difficulty with written tasks because of difficulties with fine motor skills. The visual-motor coordination and fine motor movements that are required in written activities may be extremely frustrating and divert the student’s attention from the content of what he is writing to the physical process of print production. Difficulties with handwriting have been identified as one of the most significant barriers to academic participation for students with ASD in schools today.

There are many ways in which technology can be used to enhance and compensate for the limitations that students have in their writing skills. If fine motor skills are a barrier to participation and academic function, then seek the alternative of assistive technology.

The use of keyboards, word processors, and writing software has facilitated the writing process for many students with ASD. Learning to use a keyboard is a valuable skill for students to acquire. For many students with ASD, using a computer is a highly preferred activity. Teach and encourage the student to learn to use the keyboard as a writing instrument. This is a reasonable accommodation to the motor planning difficulties often associated with ASD. While learning to print can be a useful exercise for many, when students’ difficulties with penmanship inhibit their ability to demonstrate their knowledge and spark behavioural upsets, the use of the keyboard is a viable alternative.

In many cases, OTs are involved with students with ASD and provide assessments and information on a student’s fine motor and writing skills. OTs can provide recommendations about the strategies, resources, and accommodations that will be appropriate to assist students with fine motor and writing difficulties. As with other skills, it is essential to focus on the students’ strengths and determine the skills and methods that will be most functional for the students in the future.

Mathematics For many students with ASD, participation in mathematics can be a challenging aspect of the academic curriculum. There are several reasons for this:

• Although many mathematical concepts can be demonstrated through visual examples, they are often accompanied by sophisticated verbal instruction.

• The language of mathematics instruction has its own vocabulary, and the precision of instruction and usage of terms can vary from one instructor to another.

• Mathematical terminology can be very complex and is challenging for students who struggle with processing the language of everyday interactions.

• Along with the verbal, orthographic, and representational expressions of number, there is also the symbolic representation in the form of numerals.

• Mathematical operations are usually performed with a pencil. Many students with ASD have fine motor difficulties and learning to form numerals and manipulate them on paper may be challenging.

3.5 Vocational Training and Career Opportunities

Provisions to meet the educational needs of individuals with autism are geared to enabling them to lead as independent a life as possible in adulthood. This implies that education would provide the individuals with work skills that would make them eligible for seeking employment, obtain employment, retain their jobs, be able to live independently, and have adequate leisure skills. Yet the few educational opportunities that currently exist are more focused on the development of cognitive skills and on ‘academics’ and pay little attention to the needs of individuals for when they become adults with autism. This near-absence of appropriate educational opportunities severely limits the possibility for employment—and therefore, the opportunities for independent living— for the vast majority of individuals with autism. In order to maximize the options for adults with autism to be independent as adults, current services and planning must also take into consideration the need for training in vocational skills, job opportunities, living options, and recreational opportunities.

Vocational Training

Training in work skills among young adults and adults with autism needs to focus on their strengths. In general, individuals with autism perform best at jobs which are structured and involve a degree of repetition. They thrive in an environment that is structured and well organized. Persons with autism often excel in tasks involving numbers, book keeping, data input, accounting, and tasks involving rote memory. In a job setting, they may have a good eye for detail and meticulous application of routine tasks. Given the social deficits of autism, they are best at jobs that do not involve a lot of dealing with the public, do not rely too heavily on social skills, and jobs which are routine and predictable. Most persons with autism will do happily and well on a repetitive type of job, such as putting a shuttle through a simple loom repetitively to weave long swatches of fabric, or silk screen printing. These are tasks that the non-autistic may balk at. They are also good at jobs where they might have to speak a lot, but can speak without interruption about their own interests. Training in vocational skills and employment for individuals with autism should thus focus on these strengths.

Some of the difficulties they face are with interpreting verbal and non-verbal communication, such as idiomatic language, facial expressions and body language, difficulties in jobs that require dynamic social interactions. Initiating and maintaining conversations on general topics may not be of particular interest to them. Similarly, jobs that require them to look beyond their narrow interests towards abstract ways may be difficult. Vocational training must teach skills to get a job, but more importantly, also directly teach the skills that are needed to keep those jobs.

Currently Action For Autism has a work skills training unit and that too is at a nascent stage. A few individuals have gone into the work arena, but finding open employment for most remains a difficult task.

Employment Opportunities

In addition to training in vocational skills, there are autistic individuals who are in open employment or in sheltered workshops in India, and these individuals cope with their special needs and adapt to the work environment, even in the absence of required training and supports. People who have autism are currently employed as artists, librarians, stock keepers, data entry operators, other office workers, computer operators, mail and dispatch staff, assembly line workers, accounts, and in sheltered work settings. In the successful cases, the work environment has provided the necessary support and have adapted to the needs of the individuals. Much of this has been serendipitous and without an awareness of the individual’s diagnosis of autism. Yet as both educational and workplace environments become increasingly competitive, individuals with autism will need certain provisions in order to access the workplace.

Barriers to successful employment may arise because Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) is a hidden disability and coworkers not aware of the nature of the person’s disability may easily misunderstand them. In addition, most jobs require an interview process which relies on communication and social interaction skills, areas of particular difficulty for a person with ASD. With appropriate training and matching of skills to jobs people with autism can learn meaningful job skills that enable them to successfully work in competitive employment, supported employment, or in sheltered workshop programs.

Recreation and Social Life: Opportunities and Issues

Individuals who have autism, generally have to be taught to develop leisure skills, something that most of us do naturally. However, once taught, they may develop diverse leisure interests and often enjoy the same recreational activities as their non handicapped peers. A large number enjoy music and many are great singers, working on puzzles, computer games and physical activities that can be done on their own yet alongside others such as swimming, hiking, camping, cycling, and roller skating. Because of their socially awkward ways they are often made to feel unwelcome at sports facilities, except where the parents are able to surmount such hurdles. However, there are other public areas that people with autism visit. Increasingly one finds people with autism enjoying meals in restaurants and tolerating long hours in theatres and to enjoy the experience.