1.1. CP: Nature, Types and Its Associated Conditions

Cerebral palsy (commonly referred to as CP) affects normal movement in different parts of the body and has many degrees of severity.

CP causes problems with posture, gait, muscle tone and coordination of movement.

The word “cerebral” refers to the brain’s cerebrum, which is the part of the brain that regulates motor function. “Palsy” describes the paralysis of voluntary movement in certain parts of the body.

Definition

Cerebral Palsy is a group of conditions that are characterized by chronic disorders of movement or postures; it is cortical in origin, manifests itself early in life and is not the outcome of a progressive disease.

Cerebral Palsy is a syndrome as the following a combination of characteristics can be seen:

· Motor Disorder.

· Medical Conditions.

· Sensory Impairments.

· Hearing Disabilities.

· Attention Deficits.

· Language & Perceptual Deficits.

· Behavioral Problems.

· Mental Retardation.

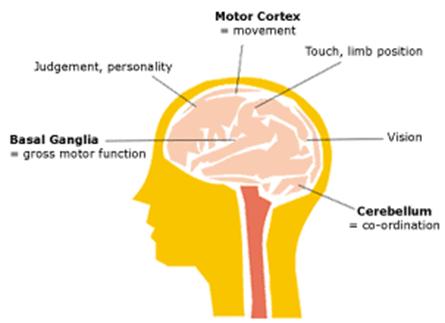

Affected Areas of the Brain

The kinds of abnormal muscle tone and movement problems that a person with cerebral palsy experiences depend upon which area of the brain is injured.

Characteristics of CP

Spastic

- Difficulties with fine motor skills due to jerky reflexes

- Stiff muscles (hypertonia)

- Exaggerated reflexes

Athetoid/dyskinetic

- Tremors and shakiness

- Involuntary reflexes

- Variations in muscle tone (hypertonia and hypotonia)

- Slow, writhing movement

Ataxic

- Lack of coordination

- Difficulty with balance

- Trouble with fine motor skills

These developmental movement disorders can be limited to: one side of the body, the legs, the arms, all four limbs or just one limb.

Conditions associated with cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy is caused by damage to or malformation of the areas of the brain that control motor function during fetal development. Children with CP often have coexisting conditions, which are health conditions that a person has in addition to cerebral palsy. These other conditions may be the result of having cerebral palsy or an unrelated, but common co-occurrence.

There are several categories of conditions associated with cerebral palsy, including:

- Primary conditions

- Secondary conditions

- Associative conditions

- Co-mitigating factors

1. Primary Conditions

Primary conditions are the direct result of the brain injury or malformation that causes cerebral palsy. Primary conditions or symptoms of cerebral palsy include impaired motor control (gross, fine and oral), impaired motor coordination and poor muscle tone, balance and posture.

2. Secondary Conditions

Secondary conditions are the result of primary conditions and are only present because of the cerebral palsy. Secondary conditions often associated with CP include difficulty feeding and swallowing, poor nutrition and respiratory issues, among others.

Oral Motor Impairment (Problems with Feeding, Swallowing and Drooling)

Children with cerebral palsy often have impaired oral motor control, which means they have difficulty controlling the muscles in their mouth and throat. This can lead to problems with feeding (sucking, chewing, etc.) and dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing. In some cases, those with dysphagia may experience pain when swallowing or be unable to swallow at all.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is common among those with cerebral palsy. GERD is a digestive disease in which stomach acid is regurgitated into the esophagus.

Children who have difficulty swallowing and/or GERD are at risk for aspiration, which is when food, liquids, saliva or vomit are inhaled into the lungs. Frequent aspiration can lead to respiratory problems, like aspiration pneumonia, and may be life-threatening.

Those with impaired fine motor skills may also have trouble using their hands to transport food or drink to their mouth. These children may have to rely on a caretaker or assistive equipment to feed them. Feeding and swallowing problems can lead to poor nutrition, dehydration and low weight.

It’s estimated that 85 to 90 percent of children with cerebral palsy experience feeding and swallowing difficulties, especially those with moderate to severe cases of CP.

Oral motor impairment also causes drooling in about 30 percent of cerebral palsy patients. Problems with feeding and swallowing, as well as drooling, can be improved through speech and occupational therapy.

Speech Impairment

Many children with cerebral palsy have dysarthria, a motor speech disorder. People with dysarthria have difficulty controlling the muscles used for speech, such as the:

- Lips

- Tongue

- Vocal folds

- Diaphragm

Apraxia of speech is another common motor speech disorder that affects children with cerebral palsy. Childhood apraxia of speech, as it’s referred to in children, is when a child has difficulty saying words, sounds and syllables. The child knows what they want to say, but their brain is unable to plan and coordinate the muscle movements needed to do so.

Children with cerebral palsy may also struggle with speech sound disorders. These include problems with articulation and phonological processes, or speech patterns used by children to simplify adult speech.

It’s estimated that more than half of children with cerebral palsy have some sort of speech impairment. Speech disorders can usually be improved through speech therapy.

3. Associative Conditions

Associative conditions are those that commonly co-occur with cerebral palsy, but are not caused by the same brain injury or malformation. Associative conditions of CP include vision and hearing impairment (these can be secondary conditions in some cases), intellectual and learning disabilities, and epilepsy, among others.

Intellectual Disabilities

Intellectual disability, formerly known as mental retardation, is characterized by below average intellectual functioning. A child with an intellectual disability will have limitations in both cognitive functioning—the thinking skills that lead to knowledge—and adaptive behavior—the ability to adapt to the environment and function in daily life. Intellectual disabilities are categorized as mild, moderate or severe.

An estimated two-thirds of children with cerebral palsy have an intellectual disability. Of those children, half have a mild diagnosis and the other half have a moderate to severe intellectual disability.

Learning Difficulties

Children with cerebral palsy sometimes have difficulty learning due to a number of factors. Some have learning disabilities, which are neurological processing problems that interfere with basic learning skills, like reading and writing. Learning disabilities can also affect higher level skills, such as organization and abstract reasoning.

Motor planning difficulties, known as motor dyspraxia, are also common with CP. People with motor dyspraxia have a hard time understanding tasks and planning how to perform them, which makes executing the tasks even harder. A child who has motor planning difficulties knows what they want to do, but they have trouble understanding how to do it. This can make learning new skills a huge effort that requires a lot of concentration.

Perceptual difficulties, which include both auditory (hearing) and visual (seeing) perception, may also affect a child with CP’s ability to learn. Children with perceptual difficulties have a hard time making sense of the information they take in through their eyes and/or ears, which can impact many areas of learning, especially learning to read and working with numbers.

Those with impaired fine motor and gross motor coordination, as well as language and communication problems, may also have trouble learning.

Visual Impairment and Blindness

Visual impairment refers to any kind of vision loss not including blindness, which is when a person is completely visually impaired and can see no light at all.

One in ten children with cerebral palsy have severe visual impairment. Nearly half of all children with spastic cerebral palsy have strabismus, better known as cross-eye. As many as 75 to 90 percent of children with CP have vision impairment, including:

- Amblyopia (lazy eye)

- Optic atrophy (deterioration of the optic nerve due to damage)

- Nystagmus (repetitive, uncontrollable eye movements in a vertical or horizontal direction)

- Visual field defects (loss of one side of the visual field)

- Refractive errors (near and farsightedness and astigmatism or blurred vision)

Hearing Loss

An estimated 20 percent of children with cerebral palsy have a hearing impairment. Early intervention is important because hearing problems can also affect the child’s speech and communication skills.

Seizure Disorder—Epilepsy

A seizure is a sudden surge of electrical activity in the brain that can cause involuntary movements and/or behavior changes, as well as a change in awareness. Epilepsy, also known as seizure disorders, is not a disease. It is a spectrum condition characterized by unpredictable, recurrent seizures.

Thirty to 50 percent of children with CP have co-occurring epilepsy. It’s more common among children who are unable to walk or have limited mobility.

Sensory Problems

A child’s ability to process information received from the senses may also be affected depending on the severity and extent of their brain injury. This is called sensory processing disorder. Children with sensory processing disorder can experience increased or decreased sensory reactions, which can lead to problems with development and behavior.

For example, a child who has an increased sensitivity to touch (known as hypersensitivity) may not like the feeling of certain textiles and will act out or scream if they come in contact with one. On the other hand, a child with a decreased sensitivity to touch (known as hyposensitivity) may play aggressively or bump into things without showing pain.

Sensory problems are common among children with other neurodevelopmental disorders, like autism.

4. Co-mitigating Factors

Co-mitigating factors are conditions that are unrelated to cerebral palsy. These conditions often coexist with cerebral palsy, but the reason why is not yet known. Co-mitigating factors of cerebral palsy include autism and ADHD.

ADHD

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disability characterized by inattention, distractibility and impulsivity. Children with ADHD may have a hard time staying focused and paying attention, which can make learning a challenge. They may also have trouble controlling their behavior and struggle with hyperactivity—a higher than normal activity level. Children with ADHD often have issues in school and with social skills.

Approximately three to five percent of children have ADHD and it’s more common in children with cerebral palsy or other brain disorders.

Autism

Autism spectrum disorder is an umbrella term that describes a group of brain development disorders. Autism is characterized by social impairments, verbal and nonverbal communication difficulties and repetitive patterns of behavior.

Approximately one to two percent of American children have an autism spectrum disorder. An estimated seven percent of children with cerebral palsy have co-occurring autism. While it seems that autism is more common among children with cerebral palsy, the link between the two disorders is not yet known.

Types/classification of CP

Physiological Grouping

- Spastic (70% of cases) — The most common type of cerebral palsy is known as spastic cerebral palsy. This is caused by damage to the brain’s motor cortex. Typical symptoms include stiff, exaggerated movements.

Spasticity is defined as a velocity-dependent increased muscle tone, determined by passively flexing and extending muscle groups across a joint. A satisfactory, reproducible system of grading muscle tone has never been developed, although the Ashworth and Tardieu scales are commonly used in research. Most physicians describe the tone as being normal, increased or decreased. Associated with spasticity are enhanced deep tendon reflexes, usually associated with clonus and extensor plantar responses. However, the latter are sometimes difficult to elicit in the infant and even in the older child with spastic CP.

- Athetoid/dyskinetic (10%) — This type is caused by injury to the brain’s basal ganglia, which controls balance and coordination. Children with athetoid/dyskinetic CP often exhibit involuntary tremors.

Dyskinesia is defined as abnormal motor movements that become obvious when the patient initiates a movement. When the patient is totally relaxed, usually in the supine position, a full range of motion and decreased muscle tone may be found. Dyskinetic patients are subdivided into two subgroups.

• The hyperkinetic or choreo-athetoid children show purposeless, often massive involuntary movements with motor overflow, that is, the initiation of a movement of one extremity leads to movement of other muscle groups.

• The dystonic group manifest abnormal shifts of general muscle tone induced by movement. Typically, these children assume and retain abnormal and distorted postures in a stereotyped pattern. Both types of dyskinesia may occur in the same patient. Simply stated, spasticity you feel; dystonia you see.

- Ataxic (10%) — Ataxic cerebral palsy is characterized by lack of coordination and balance. This is caused by damage to the cerebellum, which is the part of the brain that connects to the spine.

Patients with ataxias have a disturbance of the coordination of voluntary movements due to muscle dyssynergia. These patients may be hypotonic during the first two or three years of life. They commonly walk with a wide-based gait and have a mild intention tremor (dysmetria).

- Mixed (10%) — Some cases of cerebral palsy are classified as Mixed. This occurs when an individual exhibits symptoms of more than one type of CP.

The fourth category that is commonly used in the physiologic and motor classification is the mixed group. Patients in this category commonly have mild spasticity, dystonia, and/or athetoid movements. Ataxia may also be a component of the motoric dysfunction in patients placed in this group.

Anatomic Grouping

- Monoplegia – Paralysis of one limb

- Diplegia/Paraplegia – Paralysis of two limbs, usually the legs

- Hemiplegia – Paralysis on one side of body

- Quadriplegia – Paralysis of whole body (face, arms, legs, torso)

- Double hemiplegia – Paralysis of whole body; used to distinguish those whose arms are more affected than their legs

The distribution of cerebral palsy when the child is of low birth weight (less than 1500 grams) is as follows:

(a) Diplegia - 57%

(b) Quadriplegia - 22%

(c) Hemiplegia - 11%

(d) Mixed - 10%

The topographic classification of CP is monoplegia, hemiplegia, diplegia and quadriplegia; monoplegia and triplegia are relatively uncommon. There is a substantial overlap of the affected areas. In most studies, diplegia is the commonest form (30% – 40%), hemiplegiae is 20% – 30%, and quadriplegia accounting for 10% – 15%. In an analysis of 1000 cases of CP from India, it was found that spastic quadriplegia constituted 61% of cases followed by diplegia 22%.

Quadriplegic CP

This is the most severe form involving all four limbs, and the trunk upper limbs are more severely involved than the lower limbs, associated with acute hypoxic intrapartum asphyxia. However, this is not the only cause of spastic quadriplegia.5 Neuroimaging reveals extensive cystic degeneration of the brain – polycystic encephalomalacia and polyporencephalon MRI and a variety of developmental abnormalities such as polymicrogyria and schizencephaly. Voluntary movements are few; vasomotor changes of the extremities are common. Most children have psuedobulbar signs with difficulties in swallowing and recurrent aspiration of food material. Half the patients have optic atrophy and seizures. Intellectual impairment is severe in all cases.

Hemiplegic CP

Spastic hemiparesis is a unilateral paresis with upper limbs more severely affected than the lower limbs. It is seen in 56% of term infants and 17% of preterm infants. Pathogenesis is multifactorial. Voluntary movements are impaired with hand functions being most affected. Pincer grasp of the thumb, extension of the wrist and supination of the forearm are affected. In the lower limb, dorsiflexion and aversion of the foot are most impaired. There is increased flexor tone with hemiparetic posture, flexion at the elbow and wrist, knees and equines position of the foot. Palmer grasp may persist for many years. Sensory abnormalities in the affected limbs are common. Sterognosis impaired most frequently. 2 point discrimination and position sense is also defective. Seizures occur in more than 50%. Visual field defects, homonymous hemianopia, cranial nerve abnormalities most commonly facial nerve palsies are seen.

Diplegic CP

Spastic diplegia is associated with prematurity and low birth weight. Nearly all preterm infants with spastic diplegia exhibit cystic periventricular leukomalacia on neuroimaging. Periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) is the most common ischemic brain injury in premature infants. The ischemia occurs in the border zone at the end of arterial vascular distributions. The ischemia of PVL occurs in the white matter adjacent to the lateral ventricles. The diagnostic hallmarks of PVL are periventricular echo densities or cysts detected by cranial ultrasonography.

In this condition, lower limbs are more severely affected then the upper limbs. Mild cases may present with toe walking due to impaired dorsiflexion of the feet with increased tone of the ankles. In severe cases, there is flexion of the hips, knees and to a lesser extent elbows. When the child is held vertically, rigidity of lower limbs is most evident and adductor spasm of the lower extremities causes scissoring of the legs. Seizures are common. Fixation difficulties, nystagmus, strabismus, and blindness have been associated with PVL.

The Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS)

The Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) is often used to diagnose the severity of a child’s motor impairment. Doctors can also use the GMFCS to make a prognosis and determine the likelihood of a child improving their gross motor skills (sitting without support, walking, etc.).

The GMFCS has five levels of motor impairment from least severe (Level I) to most severe (Level V). The level of severity a child is initially diagnosed with, can be a prognostic indicator of their future motor skills.

GMFCS – The 5 Levels of Severity in Cerebral Palsy

- Level I – Fully independent, can perform most physical activities normally with only slight problems in balance or coordination.

- Level II – Trouble balancing on uneven surfaces, requires use of railings when climbing stairs, but can walk independently for the most part; minimal ability in running and jumping.

- Level III – Requires devices such as crutches or a wheelchair; may be able to climb stairs using railing.

- Level IV – Ability to walk is severely affected, most likely using wheelchair to get around.

- Level V – Significant restrictions in voluntary control; cannot walk, sit or stand independently.

Causes of cerebral palsy

- About 70 percent of cerebral palsy cases are caused by prenatal injuries

- About 20 percent are caused by injuries during birth

- About 10 percent are caused by injuries after birth

Prenatal causes

· Maternal infections. Example: rubella, herpes simplex

· Inflammation of placenta (chorionamnionitis)

· Rh incompatibility

· Diabetes during pregnancy

· Genetic causes

· Exposure to radiation

· Maternal jaundice

Peri-natal causes of cerebral palsy

· Birth asphyxia.

· Damage to the white master of the brain.

· Severe untreated jaundice, hypoglycemia.

· Sepsis (Meningitis, encephalitis).

· Premature infant with complications.

· Intracranial bleeding.

· Multiple births.

Congenital causes of cerebral palsy

· Malformation of the brain & blood vessels.

· Neurological damage as a result of

1. Intrauterine viral infections (torch).

2. Pollution (affect of environmental toxins).

3. Poor oxygenation of brain as a result of placental factors.

4. Vascular factors (Congenital heart disease, sepsis, etc).

Post-natal causes

· Infections (bacterial of viral).

· Post-surgical vascular complications.

· Asphyxia due to aspiration.

· Traumatic brain injury.

1.2. Assessment of Functional Difficulties of CP including Abnormalities of Joints and Movements (Gaits)

Physical indicators of cerebral palsy include joint contractures secondary to spastic muscles, hypotonic to spastic tone, growth delay, and persistent primitive reflexes.

The initial presentation of cerebral palsy includes early hypotonia, followed by spasticity. Generally, spasticity does not manifest until at least 6 months to 1 year of life. The neurologic evaluation includes close observation and a formal neurologic examination.

Before the formal physical examination, observation may reveal abnormal neck or truncal tone (decreased or increased, depending on age and type of cerebral palsy); asymmetric posture, strength, or gait; or abnormal coordination.

Patients with cerebral palsy may show increased reflexes, indicating the presence of an upper motor neuron lesion. This condition may also present as the persistence of primitive reflexes, such as the Moro (startle reflex) and asymmetric tonic neck reflexes (ie, fencing posture with neck turned in same direction when one arm is extended and the other is flexed). Symmetric tonic neck, palmar grasp, tonic labyrinthine, and foot placement reflexes are also noted. The Moro and tonic labyrinthine reflexes should extinguish by the time the infant is aged 4-6 months; the palmar grasp reflex, by 5-6 months; the asymmetric and symmetric tonic neck reflexes, by 6-7 months; and the foot placement reflex, before 12 months. Cerebral palsy may also include the underdevelopment or absence of postural or protective reflexes (extending arm when sitting up).

The overall gait pattern should be observed and each joint in the lower extremity and upper extremity should be assessed, as follows:

· Hip – Excessive flexion, adduction, and femoral anteversion make up the predominant motor pattern. Scissoring of the legs is common in spastic cerebral palsy.

· Knee – Flexion and extension with valgus or varus stress occur.

· Foot – Equinus, or toe walking, and varus or valgus of the hindfoot is common in cerebral palsy.

Gait abnormalities may include the crouch position with tight hip flexors and hamstrings, weak quadriceps, and/or excessive dorsiflexion.

Spastic (pyramidal) cerebral palsy

Patients with spastic (pyramidal) cerebral palsy evidence spasticity (ie, a velocity-dependent increase in tone) and constitute 75% of patients with cerebral palsy. Patients have signs of upper motor neuron involvement, including hyperreflexia, clonus, extensor Babinski response, persistent primitive reflexes, and overflow reflexes (crossed adductor). This may be observed by the child's tendency to keep the elbow in a flexed position or the hips flexed and adducted with the knees flexed and in valgus, and the ankles in equinus, resulting in toe walking.

Dyskinetic (extrapyramidal) cerebral palsy

Dyskinetic (extrapyramidal) cerebral palsy is characterized by extrapyramidal movement patterns, abnormal regulation of tone, abnormal postural control, and coordination deficits. Abnormal movement patterns may increase with stress or purposeful activity. Muscle tone is usually normal during sleep. Intelligence is normal in 78% of patients with athetoid cerebral palsy. A high incidence of sensorineural hearing loss is reported. Patients often have pseudobulbar involvement, with dysarthria, swallowing difficulties, drooling, oromotor difficulties, and abnormal speech patterns. Thus, the classic physical presentations of dyskinetic cerebral palsy include the following:

· Early hypotonia with movement disorder emerging at age 1-3 years

· Arms more affected than legs

· Deep tendon reflexes usually normal to slightly increased

· Some spasticity

· Oromotor dysfunction

· Gait difficulties

· Truncal instability

· Risk of deafness in those affected by kernicterus

These patients with dyskinetic cerebral palsy may have decreased head and truncal tone and defects in postural control and motor dysfunction such as athetosis (ie, slow, writhing, involuntary movements, particularly in the distal extremities), chorea (ie, abrupt, irregular, jerky movements) or choreoathetosis (ie, combination of athetosis and choreiform movements), and dystonia (ie, slow, sometimes rhythmic movements with increased muscle tone and abnormal postures, eg, in the jaw and upper extremities)

Spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy

Hemiplegia is characterized by weak hip flexion and ankle dorsiflexion, an overactive posterior tibialis muscle, hip hiking/circumduction, supinated foot in stance, upper extremity posturing (that is, often held with the shoulder adducted, elbow flexed, forearm pronated, wrist flexed, hand clenched in a fist with the thumb in the palm), impaired sensation, impaired 2-point discrimination, and/or impaired position sense. Some cognitive impairment is found in about 28% of these patients. Thus, spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy includes the following classic physical presentations:

· One-sided upper motor neuron deficit

· Arm generally affected more than leg; possible early hand preference or relative weakness on one side; gait possibly characterized by circumduction of lower extremity on the affected side

· Specific learning disabilities

· Oromotor dysfunction

· Possible unilateral sensory deficits

· Visual-field deficits (eg, homonymous hemianopsia) and strabismus

· Seizures

Spastic diplegic cerebral palsy

Patients with spastic diplegia often have a period of hypotonia followed by extensor spasticity in the lower extremities, with little or no functional limitation of the upper extremities. Patients have a delay in developing gross motor skills. Spastic muscle imbalance often causes persistence of infantile coxa valga and femoral anteversion. Cognitive impairment is present in approximately 30% of spastic diplegic patients. Spastic diplegic cerebral palsy includes the following classic physical presentations:

· Upper motor neuron findings in the legs more than the arms

· Scissoring gait pattern with hips flexed and adducted, knees flexed with valgus, and ankles in equinus, resulting in toe walking

· Learning disabilities and seizures less commonly than in spastic hemiplegia

Spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy

Most patients with spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy have some cognitive impairment and demonstrate the following classic physical presentations:

· All limbs affected, either full-body hypertonia or truncal hypotonia with extremity hypertonia

· Oromotor dysfunction

· Increased risk of cognitive difficulties

· Multiple medical complications (see Complications under Prognosis)

· Seizures

· Legs generally affected equally or more than arms

· Categorized as double hemiplegic if arms more involved than legs

1.3. Provision of Therapeutic Intervention and Referral of Children with CP

Although cerebral palsy is a lifelong disability, there are many interventions that can help reduce its impact on the body and the individual’s quality of life. An intervention is a service that aims to improve the condition of cerebral palsy and the day-to-day experience of the person living with it.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy addresses the child’s general strength and abilities in the areas of gross motor skills and mobility. Initial evaluations for physical therapy include looking at the child’ s posture, sensory processing, muscle tone, and coordination, developmental skills, and adaptive equipment. Direct physical therapy goals and activities are individually established based on the evaluation. They may include learning to sit, crawl, walk, climb steps, or throw or catch a ball. Activities include exercises for strengthening, range of motion and balance. Simple ball games, tricycle riding and outdoor play are used to improve coordination and endurance. Physical therapists often work with the family and local durable medical equipment vendors to identify, order, and maintain adaptive equipment to assist the child’s sitting stability, posture, and/or mobility. Typical equipment includes orthotics, activity chairs, car seats, walkers, special strollers or wheelchairs. Physical therapists also work with the child’s physicians when the the child has problems with skin breakdown, contractors, or other orthopedic problems.

Occupational Therapy

When a professional recommends occupational therapy (referred to as OT), especially for a child, the caregivers’ initial response is often one of wondering what sort of occupation a young child might need. Occupation refers to all of the “jobs” that make up our daily life, whether you are one or eighty one. OT will evaluate a child’s ability to perform self care, play, and work (school) skills at an age-appropriate level. These are referred to as ADL’s-activities of daily living. Through a comprehensive evaluation the OT can begin to identify issues that interfere with the child’s performance. This may include problems with strength, abnormal muscle tone, eye-hand coordination, visual perceptual skills, and sensory processing skills. The goal of OT is for the child to participate as actively and fully as possible in all areas of ADL’s- self care, play, and school skills.

An OT’s academic background is heavy in life sciences including gross anatomy and neuro-anatomy, as well as psychology, human growth and development, and treatment of disabilities across the lifespan. An OT addresses how the whole person is affected by his or her injury or disability, and specifically how it affects his or her ADL’s.

Pediatric OT’s often use a variety of approaches in assessing and treating children, including neuro-developmental treatment (NDT), sensory processing, and motor learning approaches. Therapy is child directed and based on activities that are meaningful and purposeful to that specific child.

OT’s also assess and incorporate various tools and adaptive equipment to increase independence. Examples include specialized feeding utensils, adaptive scissors and writing utensils, splints, and adaptations to clothing such as zipper pulls, button hooks, and reachers.

Speech-Language Therapy

Speech-language pathologists (SLP) evaluate communication skills and treat speech and language disorders. This includes receptive and expressive language, auditory processing, memory, articulation, fluency, oral-motor development, and feeding skills. The speech pathologist may also screen a child’s hearing and make a referral for further evaluation if needed.

Structured activities are used to teach specific language concepts of vocabulary and grammar, articulation and phonological training. Computers may be used to teach new concepts or reinforce previously learned information, and therapists may also use auditory/listening training. Speech pathologists may incorporate and teach alternative ways of communicating which include manual sign language, picture communication boards, and/or voice output communication devices.

Behavioral Therapy

Behavioral therapy uses psychological techniques that encourage the mastery of tasks. It is rooted in the belief that responses to emotional challenges and negative behaviors are learned and can therefore ne changed through therapy. Children do not yet possess the cognitive ability to process all that goes on with their thoughts and emotions, much less the ability to clearly communicate them. Psychotherapists are trained in identifying troubling situations, helping that child explore the thoughts, emotions and beliefs surrounding that situation, then helping the them acquire skills that will allow them to respond in a more effective and beneficial manner.

During different stages in the child’s life, and dependent upon the level of severity, a child with Cerebral Palsy may feel ostracized by peers, frustrated with treatment goals, isolated from friendships, embarrassed by medical conditions – incontinence or drooling, for example – and saddened when limited by his or her own abilities. In some cases, the child may be unable to communicate in conventional ways. The activities used in behavioral therapy vary greatly depending on the abilities of the child and the problem behavior being addressed. Activities can be designed to teach completing tasks, managing emotions, resolving conflicts, delaying gratification and any number of other basic life skills. Behavioral therapy can help alleviate depression, mood swings, sadness, loss, anger and frustration by allowing previous negative outcomes to be replaced with a more positive perspective.

Medication and Drug Therapy

A wide assortment of medications is utilized to treat Cerebral Palsy. Some reduce symptoms, while others address complications. Drug therapy is used to control body movements, prevent seizures, treat depression, relax muscles, assist digestion, and manage pain. Medication is often adjusted for tolerance and effectiveness.

Medication is often prescribed to improve associated conditions, as well. Many drugs will aid digestive problems, breathing difficulties, skin conditions, and behavioral or learning issues.

When choosing prescriptions, doctors and parents consider the benefits as well as the short- and long-term side effects. Many drugs used to treat Cerebral Palsy are very powerful, and some are not recommended for children. Some doctors may avoid prescribing certain medications to children because of the potential impact on the child’s growth and development.

Drug manufacturers change, new medications are developed, industry regulations fluctuate and insurance coverage is modified annually.

Despite extensive knowledge of the medical field and pharmaceutical industry, it is often a process of trial and error for a doctor to determine which drug will work best – and in what dosage – for any given child. Even when success is achieved, some medications must be regularly monitored and adjusted.

Certain medications are designed to target specific conditions, such as seizures, but that medication may be available in several different forms. Since every person has his or her own unique chemistry, a medication that works well for one child may have adverse effects on another. Some children may acquire tolerance of some medications and require an adjustment in dosage.

All changes in conditions, symptoms or treatment should be shared with the primary care physician to ensure drug therapy is properly prescribed.

Surgeries

There are times when surgery may be considered to improve ambulation, correct or prevent debilitating deformities, improve functioning levels, control pain, enhance appearance, or improve caregiver functions.

For those with Cerebral Palsy, orthopedic surgeries are common, but they're not the only types of surgery that may be required in the life of a person who has Cerebral Palsy.

When surgery is warranted, physicians want to minimize physical impairments and movement barriers as much as possible. The goal of orthopedic surgery is to create the ideal functional use of extremities while improving the individual’s ambulation with or without adaptive equipment. Some goals of orthopedic surgery include:

· Loosen tight or stiff muscles

· Correct curvatures

· Compensate uneven growth

· Sever nerve roots

· Correct limb positioning

· Facilitate sitting, walking, and hand use

· Reduce spasticity

· Minimize tremors

While orthopedic reasons for surgery can be numerous, some opt for surgery to improve functionality and use it to address feeding difficulties, bowel and bladder challenges, ensure joint stability, correct spinal curvatures, or minimize drooling, for example. Some may wish to decrease chronic pain levels. Others may elect surgery for appearance, hygiene or caregiver reasons. This may involve improvements in gait, standing, bracing, aligning bite, or improving the appearance of a smile.

1.4. Implications of Functional Limitations of Children with CP in Education and Creating Prosthetic Environment in School and Home: Seating Arrangements, Positioning and Handling Techniques at Home and School

Recommended activities at home and school

Stretching: Stretching of muscles is done by moving the arms or legs in a way that produces a slow, steady pull on the muscles to keep them loose. Children with cerebral palsy have increased tone and tend to get very tight muscles. Therefore, it is extremely important to perform daily stretches to keep arms and legs limber so the child can continue to move and function.

Strengthening: Strengthening exercises work specific muscle groups to enable them to support the body better and increase function.

Positioning: The body is placed in a specific position to attain long stretches. Some positions help to minimize unwanted tone. Positioning can be done in a variety of ways, including: bracing, abduction pillows, knee immobilizers, wheelchair inserts, sitting recommendations, and handling techniques.

Positioning the child in class

The head should be straight, the body symmetric, the arms straight, both hands in use and weight bearing should be equally distributed.

· Functional position should be comfortable

· Seating adaptations for children (to meet specific needs) like special cushions, corner seats, wheelchairs cut out tables, and walkers should be provided.

· Teachers should see that the aids do not restrict a child’s movement.

· Educational goals for individuals students must be developed on the basis of evaluation data.

· Consider the present physical and communication capabilities of the child.

Use of walkers

There are several types of walkers. The infant walker is designed for children from 1 ½ to 4 years of age. The child walker is for children from 2 to 8 years who are not expected to be ambulatory in future.

Instructional activities

· Place a rattle or a toy of the child’s choice on a chair in the corner of a room. Tell/gesture the child who is using an infant walker to move across the room and retrieve the toy. Then ask him to bring it to you.

· Tell/gesture the child in an upright walker to follow a group of cardboard arrows that have been placed on the floor.

· Play a “retrieval” game. Tell the child to move forward in the walker to retrieve a toy or object from a chair.

Use of crutches

Crutches are used to increase balance and stability as well as to reduce or eliminate stress on weight bearing joints. Basically they compensate for loss of muscle control. However any assistive device should be used only after the appropriate medical consultations.

Instructional activities

· Show the child the four-point gait. This gait offers maximum support because there are always three points of contact with the ground. The cycle for the child to follow is (1) right crutch forward (2) left foot forward (3) left crutch forward and (4) right foot forward. Assist the child in practicising this gait pattern.

· When appropriate, tell the child to practise going from one end of the room to the other using two-point gait. This requires the child to be able to balance on one leg and involves a significant amount of skill.

· At home, take the child to a community event such as holi celebrations or Diwali Mela. Assist him when necessary. Wait until he is ready and moves independently with crutches inside the house before you take him out.

Use of canes

Canes provide less support than crutches. Some canes are weighted with lead to provide added stability but most are not. Canes are of various types e.g. wood, aluminum, Tripod cane and so on.

Instructional activities

· Indicate to the child that he should walk towards you using his cane. Indicate that he should bring the cane and affected leg forward simultaneously and then bring the unaffected limb forward. Practice with the child and correct him when this sequence is not followed.

· Place empty paper cups next to the `x’ marks on the floor. Plan a game in which the children walk to each `x’ and pick up the empty cup. The child with the maximum cups at the end of a time limit wins the game and should be rewarded.

· In the community, take the child to a street where there is a high curb. Tell him to step up on the curb the same way he climbed stairs.

Use of wheelchair

When wheelchair is prescribed

by the doctor, it should be judged for its durability, strength, size and

weight. It should fold easily and have replaceable parts and accessories.

Instructional activities

· First practise by yourself how to unfold and fold a wheelchair. Show the child how to unfold a folded wheelchair.

· Show the child to close the wheelchair. First check to see if the arms are locked. Fold up the footrests. Make a fold in the seat from above or below. If above, pull up, closing the chair. Assist the child in carrying out each of the steps.

· Show the child how to use his wheelchair seat belt.

· Ask the child in a wheelchair to wheel the chair a very short distance. Show the child how to lock and unlock the brakes of an empty chair.

· Stand behind the child and call him to come to you in a backward movement. Show the child how to make turns in his wheelchair. Also show how if the child is in bed, can be transferred to wheelchair. Supervise all the actions till the child is independent. Use various prompts suitably and fade support gradually.

1.5. Facilitating Teaching-Learning of Children with CP in School, IEP, Developing TLM; Assistive Technology to Facilitate Learning and Functional Activities

Recommended Teaching Methods for Students with CP

When deciding that a student with CP would have their interests best served in a mainstream classroom environment, teachers, parents, and therapists should develop an Individualized Educational Plan (IEP). The IEP should detail information on the child's diagnosis and the degree to which the child is affected by the condition. This includes listing the child's present level of performance in the various subject areas. These performance levels should describe in detail what the child is able to accomplish and what their current skill levels are. In any of the areas in which the child is functioning below age level, goals and objectives should be written to address the areas of weakness.

The IEP should also include a list of services and accommodations that the school district will provide. Teaching children with cerebral palsy is often an unfamiliar circumstance for a regular education instructor, but with assistance from therapeutic programs and access to modifications in the classroom, students with CP can thrive in a general setting alongside their non-disabled peers.

It is important for children with CP to have an educational program that is conducive for learning. When setting up a learning program, teachers should consider the child’s capabilities as well as limitations, and keep in mind that unrealistic expectations can be frustrating for the child as well as the parents. Patience is a key factor when working with children with CP, as studies have shown that these students take longer to respond than their neurotypical peers.

It is important for students with CP to assume a variety of positions throughout the school day in order to prevent tightening of muscles. Equipment needs are extremely important, as proper positioning can facilitate eye-hand coordination and improved motor control. Most importantly, teachers should maintain open communication with the child’s family in order to encourage carry-over regarding home programs and recommendations.

Teaching strategies

· Break tasks and assignments into short, easy-to-manage steps. Provide each step separately and give feedback along the way.

· Provide copies of notes or use student writers if handwriting is difficult.

· Provide clear expectations, consistency, structure and routine for the entire class. Rules should be specific, direct, written down and applied consistently.

· Give clear, brief directions. Give written or visual directions as well as oral ones. Allow extra time for oral responses.

· Teach strategies for what to do while waiting for help (e.g. underline, highlight or rephrase directions; jot down key words or questions on sticky notes).

· If the student uses an alternative form of communication, like a communication book or device, make sure it is available to him or her at recess and lunchtime. Teach peers how interact with the student using the communication device or book.

· Use low-key cues, such as touching the student's desk to signal the student to think about what he or she is doing without drawing the attention of classmates.

· Use instructional strategies that include memory prompts. Teach strategies for self-monitoring, such as making daily lists and personal checklists for areas of difficulty.

Assistive technology for limited mobility

There are numerous mobility aids, also called assistive technologies or assistive devices, to help with mobility limitations associated with cerebral palsy. Most assistive devices can be adjusted to fit a child’s height or can be specially made to fit their individual needs. Assistive devices greatly improve a child’s quality of life, as well as increase their independence.

Orthotic Devices

Orthotic devices are braces worn externally that improve and strengthen mobility. There are two types of orthotic devices: accommodative orthotics and functional orthotics.

Accommodative orthotics are “over the counter” devices, which means they do not require a prescription or the approval of a doctor to be purchased. They are made in various sizes to fit anyone and can be bought in most pharmacies or sporting goods stores.Functional orthotics are specifically made for the individual.

Functional orthotics are commonly used by those with cerebral palsy because they can be customized to fit the individual’s needs.

Orthotic devices come in hard, semi-soft or soft forms. There are many types of orthotic braces, including:

- Foot orthotics

- Ankle-foot orthotics

- Hip-knee-ankle-foot orthotics

- Knee-ankle orthotics

- Knee orthotics

- Spinal orthotics

- Trunk-hip-knee-ankle-foot orthotics

- Prophylactic braces (mostly used for knee injuries)

Walkers

Walkers can assist children with cerebral palsy with their mobility issues, including problems with balance and posture. They also allow the child to bear weight on their legs, which increases bone strength and reduces the risk of fractures and osteoporosis.

There are several kinds of walkers available to help those with cerebral palsy, such as:

- Four-wheeled posture control walkers – These walkers have four posts with wheels on each. They can help children who have issues with balance and posture.

- Two-wheeled posture control walkers – These walkers also have four posts. The two posts in the front have wheels and the two posts in the back have rubber tips. The rubber tips on the rear posts allow for slower walking and more controlled movements, which is beneficial for those with severe balance impairments. These walkers also come with a built-in seat option to help with fatigue.

- Chest-support walkers – These walkers have four posts with wheels on each and a chest-support system to stabilize the trunk. They are ideal for children who do not have the ability to use their arms as needed for a traditional walker, but they can support their weight on their legs.

- Gait trainers – Gait trainers usually have four wheels and can help a child learn to walk properly, maintain momentum and build muscle skills. They have a built-in seat that allows the child to go from sitting to standing easily and often. They can come with a trunk component for those without the ability to support their own body weight while standing. They can also come with a harness to help improve posture, as well as head support attachments to improve head control.

- Suspension walkers – Suspension walkers are useful for those who have balance and posture issues and cannot support their full body weight while upright. These walkers have four posts with wheels on each and a suspension frame over head. A harness with a motorized lift attaches to the suspension frame, allowing the child to control how much weight they bear on their legs.

Walking Sticks and Canes

Walking sticks and canes are a cost effective option that provide extra balance and stability for those with milder forms of cerebral palsy. They are most helpful in patients with hemiplegia or monoplegia.

Canes and walking sticks can be adjusted to fit the child’s height. There are several types of canes, including:

- Non-folding canes

- Folding canes

- Quad or tripod base canes (these provide a better base for support)

- Folding seat canes (folds out to a seat to help with fatigue)

Crutches

Crutches are often used by those with cerebral palsy who have the ability to ambulate, or walk, but need extra help with balance and stability. There are two types or crutches: underarm crutches and forearm, or elbow, crutches.

Underarm crutches are mostly used for short term disability, like a broken leg. Forearm crutches are used for long term or lifelong disabilities and more commonly used by cerebral palsy patients. These crutches attach to the forearms and help with balance, but are not meant to take on the user’s full weight.

Standers

Standers are devices that allow those with cerebral palsy to stand for short or extended periods of time. They help to support a person’s weight and provide stability while in the upright position.

There are many benefits of using a stander. Standers:

- Allow for weight bearing in the legs

- Facilitate bone and muscle development

- Reduce the risk of developing osteoporosis

- Encourage lower extremity use

- Allow for prolonged passive stretch of the hamstrings and hip flexors

- Improve bowel and bladder functions

- Allow the child to be at eye-level with peers, which helps them to connect mentally and emotionally with others

- Increase alertness

- Stimulate the development of motor coordination and head control

The following types of standers may be helpful to those with cerebral palsy:

- Sit-to-stand standers – As the name suggests, these standers allow children to move from sitting to standing and vice versa. These standers require some head and trunk control.

- Prone, supine and multi-position standers – These standers are commonly used by children with cerebral palsy. Prone standers position the child up right on their belly, while supine standers position them on their back. Standers that allow for both the prone and supine positioning are called multi-position standers.

- Mobile standers – Mobile standers allow children to stand upright and propel themselves forward. They come in a sit-to-stand option with pulleys to propel movement, a motorized option and a prone stander option with large wheels on each side. Some head control and upper body strength are required to use these standers.

- Active standers – These standers are relatively new and are similar to mobile standers. They come in a sit-to-stand option and either the arms, legs or a combination of the two can be used to move the device. This stander also requires some head control and upper body strength for independent use.

Lifts

There are a number of lift options to help those who have difficulty transferring positions and supporting their body weight. Some lifts that are helpful with cerebral palsy include:

- Stair lifts – These carry patients up and down the stairs and are installed into the staircase to ensure safety.

- Ceiling lifts – These lifts run on a track system that is installed in the ceiling of the patient’s home. They help to transfer patients from device to device within a room or from room to room.

- Patient/pediatric transfer lifts – These lifts help to transfer patients from moving from one position or device to another. These lifts have numerous uses, like helping a patient out of bed and into a wheelchair or out of a wheelchair and into a car.

- Floor lifts – Floor lifts are also very versatile and can help with a number of lifting needs, like moving a child from room to room. They come in manual or power options.

- Sit-to-stand lifts – These lifts help patients move from a sitting position to an upright standing position. They are very useful for transfers and for toileting.

Wheelchairs

Wheelchairs are common mobility aids for non-ambulatory cerebral palsy patients. There are numerous design options and features to choose from, but there are two basic types: manual wheelchairs and power, or electric, wheelchairs.

Manual wheelchairs must be propelled by the user or pushed by another person, while power wheelchairs are motorized.

Manual wheelchairs are a more cost effective option, but they do require upper body strength to move them. There are several types of manual wheelchairs, including:

- Rigid frame wheelchairs – These chairs do not fold and take up more space. However, they are often lighter than other chairs and require less maintenance.

- Folding frame wheelchairs – Folding frame wheelchairs fold to save space and for storage purposes. These models are often heavier than rigid frame wheelchairs and are not as customizable to fit the patient’s specific needs.

- Reclining wheelchairs – As the name suggests, these wheelchairs recline to allow for more comfort. These chairs are similar in frame to folding frame wheelchairs, but these chairs usually require more maintenance.

Power wheelchairs are more expensive, but are more convenient for those who do not have the ability to propel a manual wheelchair. They’re also well suited for those who maintain an active lifestyle. These chairs come with many different features and options. They’re also very customizable to an individual’s needs. Electric wheelchairs come in rear wheel, front wheel or mid wheel drive and have a variety of different battery options.

It’s important to consider the following when buying a wheelchair:

- Type of wheelchair (manual or power) needed

- Where the wheelchair will be used (indoor, outdoor or both)

- Weight of the wheelchair

- How the wheelchair will be used (daily activities, outdoor activities, sport, etc.)

- How the wheelchair will be transported (a large vehicle and transport lift may be needed for heavier power models, whereas a folding frame chair fits easily in most cars)

- Seat width and height

- Seat cushioning

- Armrest preference (some are adjustable or removable)

- Leg and foot rest requirements

- Type of battery (if buying an electric wheelchair)

- Size and type of tire

- Cost and financing

Power Scooters

Power scooters are an alternative to wheelchairs and are often cheaper than power wheelchairs. They’re great for use outdoors and for those who do not have the upper body strength to operate a manual wheelchair.

While power scooters are more compact than power wheelchairs, they’re more difficult to maneuver because of their longer design. They’re also not as customizable for day-to-day activities and can be difficult to transport because of their heavy weight.

Communication Devices

Children with various types of cerebral palsy often struggle with the essential ability to communicate. This is due to symptoms of CP such as muscle spasms in the throat, mouth and tongue. These physical limitations make it difficult to form words or sentences, which can make daily life a challenge for children and parents alike.

Assistive communication devices empower a child with CP to meaningfully contribute to conversations and form friendships and relationships. With the help of these devices, children with CP are able to ask questions, express emotions and actively engage in the world around them.

Electronic Communication Boards

An electronic communication board is a tool that allows children to choose letters, words and phrases on a screen to verbally express their thoughts and emotions. These boards are similar to electronic tablets and contain letters, images, photos and symbols that a child can point to with their finger or a pointer tool. Then, the selected words or symbols are generated into sentences that are read out loud for others.

Images and phrases are organized into categories such as food, people, sports and objects so that children can easily search and select the words or phrases they want. Generally, communication boards can produce 8-12 words per minute.

The level of training needed to operate a communication board depends on the child’s existing level of literacy, as they may need to be taught the meaning of symbols and images before using the device. This can be done in speech therapy where a Speech Language Pathologist (SLP) will teach the child how to use the assistive device to communicate.

Communication boards come in two basic types:

- High-tech boards — includes speech generation and eye-tracking technology to assist children with limited mobility in arms, hands or fingers

- Low-tech boards — a basic sheet of paper that allows children to point to letters or words to display what they want to communicate

Eye-Tracking Devices

Oftentimes, individuals with cerebral palsy have difficulty moving their arms, wrists, hands or fingers. This can make selecting images or symbols on a communication board difficult. Fortunately, there is eye-tracking technology available that eliminates the need to actually push a button or use a pointer.

Many high-tech communication boards feature eye-tracking technology that functions like a mouse on a computer, allowing users to make eye contact with a symbol or letter for a short period of time to make a selection. Once a symbol has been “selected,” it is received by the device in the same way it would have been with a physical point or click.

Eye-tracking devices are incredibly helpful for children with a more severe level of CP that limits their upper mobility. This type of technology is often utilized during speech therapy and treatment to improve the ability to express thoughts and ideas. Parents of children who have limited movement in their arms, hands or fingers should seek out communication devices that operate using eye-tracking technology. This will assure that a child’s development or communication isn’t being restricted by physical capabilities.

Adaptive Writing and Typing Aids

Children with CP often have reduced hand or finger movement, as well as decreased grasping power and strength. This can affect their ability to write or type, as they may have difficulty using a traditional writing utensil or keyboard.

Adaptive tools that help children with disabilities gain control over their movements and perform tasks such as writing and typing are instrumental to ensuring that they stay on track with their educational program.

Writing Aids

There are various aids that can help individuals with CP learn the valuable skill of writing without having to worry about being in pain or straining different parts of the body.

Writing aids come in the form of:

- Pencil or pen grips — available in various shapes and colors to help children comfortably hold onto their writing utensil while activating the proper hand muscles for better handwriting

- Weighted pen or pencil — the weight can be transferred to any writing utensil and is used to provide children with extra leverage and guidance as they learn the mechanics behind writing

- Slanted writing board — provides a flat, customizable surface for children with disabilities to write on. The angle of the board will help keep muscles relaxed and properly aligned as they improve fine motor skills needed to write

Typing Aids

For children with limited mobility in their hands and arms, a typing aid can be extremely beneficial to provide the additional support needed to press small buttons or keys on devices such as communication boards.

Typing aids are fastened around the hand with a Velcro or elastic brace and come with a metal or steel “pointer” that extends out of the brace. Individuals can use the “pointer” of the typing aid to press down on the keys on a keyboard or to steadily push smaller buttons, such as on a telephone or calculator. This can allow children to use technology that was previously difficult for them, as it is transferrable to any device.

Specialized technology devices provide individuals with cerebral palsy the opportunity to enjoy life independently. Devices are available in various shapes and sizes to ensure that every child with CP is able to receive the assistance they need as they transition into adulthood.

Benefits to using assistive devices include:

- Improved educational performance and staying on track with school program

- Ability to clearly express feelings, thoughts and emotions

- Increased vocabulary, comprehension and reading level

- Devices can be mounted on mobility aids to meet child’s needs throughout maturity

- Parents no longer have to guess their child’s wants or needs

- Communication skills will enable employment and independent living

Similar to mobility aids, the overall advantage to using assistive devices is that they allow for an improved quality of life for a child with cerebral palsy. With the help of these tools and devices, children with CP are given the opportunity to be self-sufficient and participate in everyday life with confidence.