EDWARD C. TOLMAN'S PURPOSIVE BEHAVIORISM

Tolman originally started his academic life studying physics, mathematics, and chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). After reading William James' Principles of Psychology, he decided to shift his focus to the study of psychology. He enrolled at Harvard where he worked in Hugo Munsterberg's lab. In addition to being influenced by James, he also later said that his work was heavily influenced by Kurt Koffka and Kurt Lewin. He graduated with a Ph.D. in 1915.

Although strict behaviorists such as Skinner and Watson refused to believe that cognition (such as thoughts and expectations) plays a role in learning, another behaviorist, Edward C. Tolman, had a different opinion. Tolman’s experiments with rats demonstrated that organisms can learn even if they do not receive immediate reinforcement (Tolman & Honzik, 1930; Tolman, Ritchie, & Kalish, 1946).

Latent learning is a form of learning that is not immediately expressed in an overt response. It occurs without any obvious reinforcement of the behavior or associations that are learned. Latent learning is not readily apparent to the researcher because it is not shown behaviorally until there is sufficient motivation. This type of learning broke the constraints of behaviorism, which stated that processes must be directly observable and that learning was the direct consequence of conditioning to stimuli.

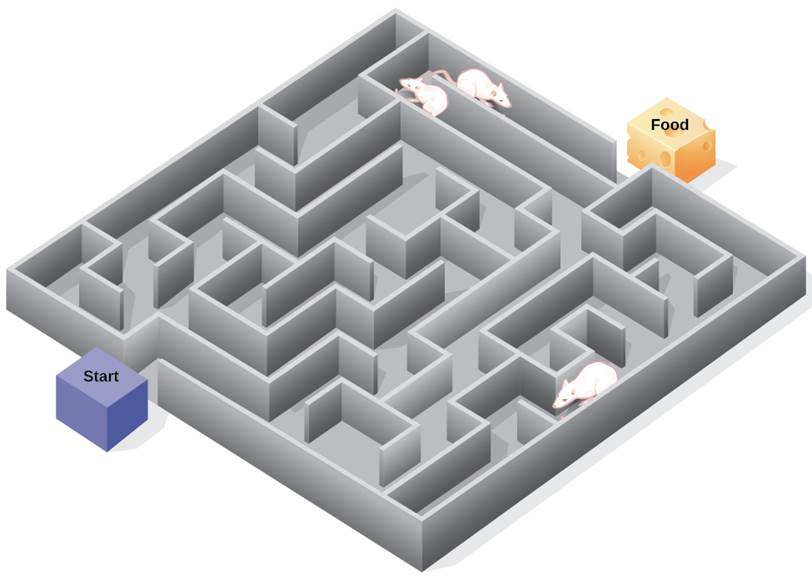

In the experiments, Tolman placed hungry rats in a maze with no reward for finding their way through it. He also studied a comparison group that was rewarded with food at the end of the maze. As the unreinforced rats explored the maze, they developed a cognitive map: a mental picture of the layout of the maze (Figure 1). After 10 sessions in the maze without reinforcement, food was placed in a goal box at the end of the maze. As soon as the rats became aware of the food, they were able to find their way through the maze quickly, just as quickly as the comparison group, which had been rewarded with food all along. This is known as latent learning: learning that occurs but is not observable in behavior until there is a reason to demonstrate it.

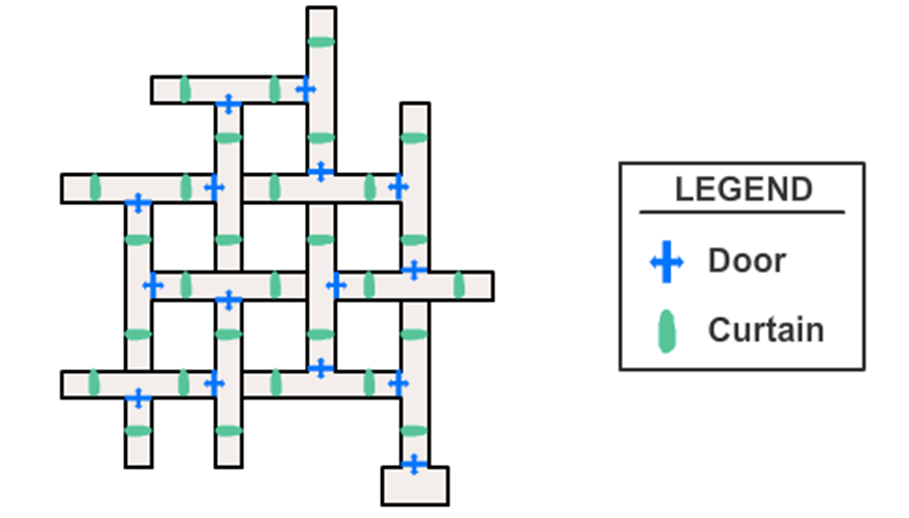

Figure 1. Psychologist Edward Tolman found that rats use cognitive maps to navigate through a maze. Have you ever worked your way through various levels on a video game? You learned when to turn left or right, move up or down. In that case you were relying on a cognitive map, just like the rats in a maze. (credit: modification of work by “FutUndBeidl”/Flickr)

Latent learning also occurs in humans. Children may learn by watching the actions of their parents but only demonstrate it at a later date, when the learned material is needed. For example, suppose that Ravi’s dad drives him to school every day. In this way, Ravi learns the route from his house to his school, but he’s never driven there himself, so he has not had a chance to demonstrate that he’s learned the way. One morning Ravi’s dad has to leave early for a meeting, so he can’t drive Ravi to school. Instead, Ravi follows the same route on his bike that his dad would have taken in the car. This demonstrates latent learning. Ravi had learned the route to school, but had no need to demonstrate this knowledge earlier.

Tolman’s Experiment

Edward Tolman was studying traditional trial-and-error learning when he realized that some of his research subjects (rats) actually knew more than their behavior initially indicated. In one of Tolman’s classic experiments, he observed the behavior of three groups of hungry rats that were learning to navigate mazes.

The first group always received a food reward at the end of the maze, so the payoff for learning the maze was real and immediate. The second group never received any food reward, so there was no incentive to learn to navigate the maze effectively. The third group was like the second group for the first 10 days, but on the 11th day, food was now placed at the end of the maze.

As you might expect when considering the principles of conditioning, the rats in the first group quickly learned to negotiate the maze, while the rats of the second group seemed to wander aimlessly through it. The rats in the third group, however, although they wandered aimlessly for the first 10 days, quickly learned to navigate to the end of the maze as soon as they received food on day 11. By the next day, the rats in the third group had caught up in their learning to the rats that had been rewarded from the beginning. It was clear to Tolman that the rats that had been allowed to experience the maze, even without any reinforcement, had nevertheless learned something, and Tolman called this latent learning. Latent learning is to learning that is not reinforced and not demonstrated until there is motivation to do so. Tolman argued that the rats had formed a “cognitive map” of the maze but did not demonstrate this knowledge until they received reinforcement.

Figure 2. The maze. As you can see from the map, the maze had lots of doors and curtains to make it difficult for the rats to master. The blue marks represent doors that swung both directions, which prevented the rat from seeing most of the junctions as it approached. This forced the rat to go through the door to discover what was on the other side. The green forms show curtains. These hung down and prevented the rat from getting a long distance perspective and it also meant that they could not see a wall at the end of a wrong turn until they had already made a choice and moved in that direction. The rat was always in a small area, unable to see beyond the next door or curtain, so learning the maze was a formidable task.

Procedure

In their study 3 groups of rats had to find their way around a complex maze. At the end of the maze there was a food box. Some groups of rats got to eat the food, some did not, and for some rats the food was only available after 10 days.

Group 1: Rewarded

- Day 1 – 17: Every time they got to end, given food (i.e. reinforced).

Group 2: Delayed Reward

- Day 1 - 10: Every time they got to end, taken out.

- Day 11 -17: Every time they got to end, given food (i.e. reinforced).

Group 3: No reward

- Day 1 – 17: Every time they got to end, taken out.

Results

The delayed reward group learned the route on days 1 to 10 and formed a cognitive map of the maze. They took longer to reach the end of the maze because there was no motivation for them to perform.

From day 11 onwards they had a motivation to perform (i.e. food) and reached the end before the reward group.

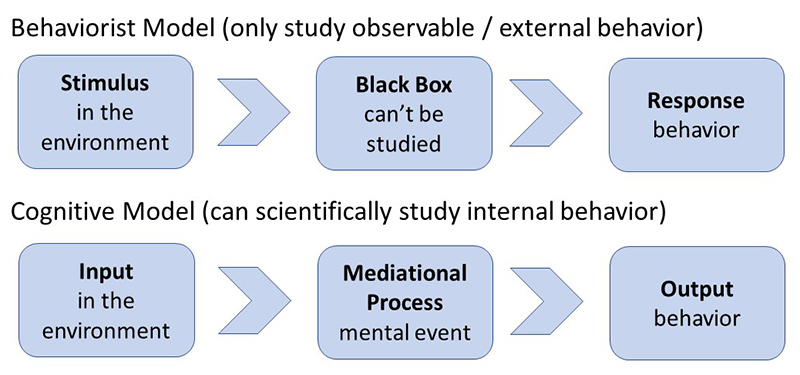

This shows that between stimulus (the maze) and response (reaching the end of the maze) a mediational process was occurring the rats were actively processing information in their brains by mentally using their cognitive map (which they had latently learned).

Sign Learning (E. Tolman)

Tolman’s theorizing has been called purposive behaviorism and is often considered the bridge between behaviorism and cognitive theory. According to Tolman’s theory of sign learning, an organism learns by pursuing signs to a goal, i.e., learning is acquired through meaningful behavior. Tolman emphasized the organized aspect of learning: “The stimuli which are allowed in are not connected by just simple one-to-one switches to the outgoing responses. Rather the incoming impulses are usually worked over and elaborated in the central control room into a tentative cognitive-like map of the environment. And it is this tentative map, indicating routes and paths and environmental relationships, which finally determines what responses, if any, the animal will finally make.” (Tolman, 1948, p192)

Tolman (1932) proposed five types of learning: (1) approach learning, (2) escape learning, (3) avoidance learning, (4) choice-point learning, and (5) latent learning. All forms of learning depend upon means-end readiness, i.e., goal-oriented behavior, mediated by expectations, perceptions, representations, and other internal or environmental variables.

Tolman’s version of behaviorism emphasized the relationships between stimuli rather than stimulus-response (Tolman, 1922). According to Tolman, a new stimulus (the sign) becomes associated with already meaningful stimuli (the significate) through a series of pairings; there was no need for reinforcement in order to establish learning. For this reason, Tolman’s theory was closer to the connectionist framework of Thorndike than the drive reduction theory of drive reduction theory of Hull or other behaviorists.

Application

Although Tolman intended his theory to apply to human learning, almost all of his research was done with rats and mazes. Tolman (1942) examines motivation towards war, but this work is not directly related to his learning theory.

Example

Much of Tolman’s research was done in the context of place learning. In the most famous experiments, one group of rats was placed at random starting locations in a maze but the food was always in the same location. Another group of rats had the food placed in different locations which always required exactly the same pattern of turns from their starting location. The group that had the food in the same location performed much better than the other group, supposedly demonstrating that they had learned the location rather than a specific sequence of turns.

Principles

1. Learning is always purposive and goal-directed.

2. Learning often involves the use of environmental factors to achieve a goal (e.g., means-ends-analysis)

3. Organisms will select the shortest or easiest path to achieve a goal.

Critical Evaluation

The behaviorists stated that psychology should study actual observable behavior, and that nothing happens between stimulus and response (i.e. no cognitive processes take place).

Edward Tolman (1948) challenged these assumptions by proposing that people and animals are active information processes and not passive learners as Behaviorism had suggested. Tolman developed a cognitive view of learning that has become popular in modern psychology.

Tolman believed individuals do more than merely respond to stimuli; they act on beliefs, attitudes, changing conditions, and they strive toward goals. Tolman is virtually the only behaviorists who found the stimulus-response theory unacceptable, because reinforcement was not necessary for learning to occur. He felt behavior was mainly cognitive.