Unit 2: Auditory Learning (AVT & Auditory Training) & Speech Reading

2.1 Concept of ‘Auditory Listening’: Unisensory & Multisensory approaches

2.2 Auditory training: Importance, types (Individual & Group) and Stages

2.3 Auditory Verbal Therapy: Principle, importance and role of teacher

2.4 Auditory Training and AVT: Pre-requisites, challenges, similarities & differences

2.5 Speech Reading: Concept, importance, Pre-requisites, challenges and Role of teacher

2.1 Concept of ‘Auditory Listening’: Unisensory & Multisensory approaches

Everyone has their own unique ways that they learn. These learning styles are critical for finding success in the classroom—students and teachers who understand different learning styles are able to focus their education and use different strategies to find the greatest success in the classroom.

Teachers in particular can benefit from understanding all the different learning styles, as they will likely have students who fall under each category in their classroom at one time or another. Being able to identify student learning preferences, cater classroom activities to different learners, and overall help improve all student outcomes, is key to being a good teacher.

There are a few main learning styles which are visual, kinesthetic, and auditory. Sometimes reading/writing is also considered a category for learning. While these categories are fairly self-explanatory, there are important elements of each that explain how and why learners thrive with this kind of learning. It’s also extremely important for teachers to understand how to identify students’ learning styles, help them work to understand in new ways, and provide them opportunities to learn in the way that is easiest for them.

Auditory learning refers to a learning style in which people learn most effectively by listening. An auditory learner prefers to listen to the information rather than read it in a text. While other learners retain information in different ways, either by touch, vision, or reading, an auditory learner will focus on listening or speaking to process the information.

Many auditory learners find learning challenging when the data is delivered to them in a written text but have no problem understanding it in an audial form. They store information by how it sounds and often learn new things by reading them aloud or pairing them to non-verbal sounds like music or clapping. For example, children who are auditory learners love music and tend to learn the words of songs more quickly than other types of learners. They have no problem understanding spoken directions by their teachers, but when asked to read something, they will instead prefer to read aloud to have someone read it to them.

Auditory learners usually excel in traditional school environments where they use listening as their primary way of learning.

Auditory learning characteristics.

There are many great characteristics that auditory learners have them help them thrive in classroom settings. Some of their characteristics include:

· Good memory for spoken information

· Good public speaking abilities

· Eloquent

· Strong listening skills

· Excel in oral presentations and exams

· Good at telling stories

· Good ability to read aloud and retain information

· Distracted by background noises

· Distracted by silence

· Enjoys conversations

· Unafraid to voice their thoughts

· Good member in study groups and collaboration projects

· Able to understand and process changes in tone

· Works through complex problems by talking out loud

· Able to explain ideas well

· Solid communication abilities

We learn language by hearing it from the moment of birth. Even after our language has fully developed, we continue to learn new words and new ways of expressing ideas. This learning happens largely through our sense of hearing. Much of what we know about our world is learned by overhearing the conversations of those around us, or through the myriad of audio streams that follow us through our day. When a child is born with reduced hearing, the development of language, vocabulary, and world knowledge can be affected.

Hearing aids and other devices can provide improved access to spoken language for children with hearing loss. Auditory aids, however, do not fix hearing to the degree that eyeglasses can ‘fix’ a vision deficit. What a student hears through an auditory aid is likely not what you and I hear through the device. A student may hear what is said in the classroom, but may not understand the message due to many factors, such as incomplete access to speech sounds, background noise, unfamiliar vocabulary, delayed language development or a lack of familiarity with the person talking.

Many children can improve their understanding of spoken language as they become familiar with their hearing loss and learn listening strategies. Practice with specific listening skills may further increase the benefit a student receives from hearing aids or cochlear implants.

Information is provided within this section of the website on auditory development, listening skills and more.

Learning to Listen

- A child needs to be able to interpret and attach meaning to information they receive from what they have heard and formulate a response

- Attaching meaning depends on their lexicon (vocabulary ‘dictionary’) helped by their ability to visualize

- Listening comprehension is a key to reading comprehension and written composition

- Listening comprehension = language ability + background knowledge

- Listening Comprehension x Decoding = Reading Comprehension

- It all starts with being able to listen precisely!

Over the years, a lot of terminologies have been used to enable the individuals to use their auditory mechanism for communication. Some of the terms that have been used include auditory training, listening training, and acoustic training. These three are used interchangeably and the most commonly used term is auditory training.

The other terms used include auditory learning. There are also other approaches that have been given specific terminologies such as auditory verbal therapy (AVT), auditory-oral method, and aural-oral method. So it is required these terms be defined.

Auditory learning: It is one in which activities for developing spoken language are related to the children real life experience and language stresses the comprehension of meaningful sounds which is considered to be highest level of auditory behavior (Erber, 1982; Sanders, 1982).

Auditory-oral method: It’s a method to teach language both receptive as well as expressive to children with hearing impairment. Some believe that along with the auditory cue speech reading can also be carried out.

Aural-oral method: It is a method where the child develops/ taught language through the auditory mechanism and communicates through speech.

Most children who are deaf or hard-of-hearing have some hearing. This is called “residual hearing“. Some parents of a child with residual hearing may choose to use a building block called listening (auditory training). This building block is often used in combination with technology (such as hearing aids, cochlear implants, and other assistive devices)

Listening might seem easy to a person with hearing. But for a child with hearing loss, listening is often hard without proper training. Like all other building blocks, the skill of listening must be learned. Often a speech-language pathologist will work with the baby and family.

Many parents look for help in learning to use these special skills. There are several programs that can help parents and children, each emphasizing different language learning skills. Here are the five programs, and the skills that are sometimes included in each of them:

Auditory-Oral: The auditory-oral program teaches babies and young children who are deaf or hard-of-hearing to use whatever hearing they have. They also use lipreading (speechreading) and gestures to understand and use spoken language. This program includes building blocks such as Natural Gestures, Listening, Speech (Lip) Reading, and Speech.

Auditory-Verbal: The auditory-verbal program teaches babies and young children who are deaf or hard of hearing to use their amplified residual hearing or hearing through electrical stimulation (cochlear implants) to listen, to understand spoken language, and to speak. This program includes building blocks such as Listening and Speech.

Bilingual: This program teaches babies and young children who are deaf or hard of hearing two languages, American Sign Language (ASL) and the family’s native language. (for example, English or Spanish). ASL is usually taught as the child’s first language and English (or the family’s native language) is taught as the child’s second language through reading, writing, speech, and use of residual hearing. This program also teaches respect for Deaf and hearing cultures. This program also includes building blocks such as Finger Spelling and Natural Gestures.

Cued Speech (Building Block): Cued Speech (sometimes called “cueing”) is a building block that helps children who are deaf or hard-of-hearing better understand spoken languages. Many speech sounds look the same on the face even though the sounds are different. For instance, the words “mat”, “bat”, and “pat” look the same on the lips and mouth. When “cueing” English, the person communicating uses eight hand shapes and four places near the mouth to help the person looking tell the difference between speech sounds.

Total Communication: The Total Communication program teaches babies and young children that are deaf or hard-of-hearing to use a combination of building blocks to communicate in the English language. Most Total Communication programs use some form of Simultaneous Communication (speaking and signing at the same time). This program includes building blocks such as Conceptually Accurate Signed English (CASE), Finger Spelling, Listening, Manually Coded English (MCE), Natural Gestures, Speech (Lip) Reading, and Speech.

The history of and current controversy in education of the hearing impaired between advocates of unisensory (hearing only) and multisensory (hearing, vision and touch) approaches to communication for learning and socialization for hearing-impaired children is described.

Supporters of a unisensory perspective suggest that providing visual access to the speaker’s lips, tongue, and throat alongside auditory information competes with and inhibits a child’s processing of auditory information, which is then reflected in reduced spoken word acquisition. Pollack (1970) summarizes the unisensory position well by stating, “There can be no compromise, because once emphasis is placed upon ‘looking’ there will be divided attention, and the unimpaired modality, vision, will be victorious” (p. 18). This position has been used to support long-standing educational practices that aim to emphasize and highlight the auditory signal by limiting or eliminating access to visual cues, such as using a hand cue (i.e., covering the mouth with a flat, slanted hand; Estabrooks, 2001), speech hoops, speaking when the child is looking away, visual distractions, and positioning (Robbins, 2016).

Supporters of a multisensory theory suggest that simultaneous, integrated AV input facilitates word learning, even when input is unequal across senses (e.g., in hearing loss). Evidence in favor of the multisensory position is drawn from studies of the multisensory nature of speech perception in natural contexts (e.g., Holt, Kirk, & Hay-McCutcheon, 2011), spoken word recognition tasks in unisensory versus multisensory conditions, and associations between the degree of benefit from visual cues with language skills and speech intelligibility in children with hearing loss.

In sum, given the audio-visual-AV multisensory nature of speech perception in natural contexts, the importance of experience for multisensory integration, benefits of multisensory input for speech recognition tasks, and positive correlations between AV integration and enhancement with speech-language outcomes, one must carefully consider the possible implications of unisensory versus multisensory intervention strategies for children with hearing loss. The degree and manner in which children with hearing loss receive access to multisensory input could have important implications for speech and language outcomes.

2.2 Auditory training: Importance, types (Individual & Group) and Stages

Studies have shown that hearing loss is connected to increased social isolation and depression, as well as cognitive decline. Listening can be exhausting, and when your brain is working overtime to hear and understand what’s being said, that makes it difficult to pay attention to other things in your environment. In other words, when you’re using all your brain power to hear and understand, your brain can’t work on the other things it needs to. This is called “cognitive load.”

Auditory training, which is sometimes referred to as “aural rehabilitation,” was developed by hearing healthcare professionals to assist people with hearing loss by improving their listening skills and speech understanding. While you physically hear with your ears, your brain has to process those sounds and make sense of them. Your brain and your ears are a team. By using the auditory training program we offer, you strengthen your brain’s auditory processing capability. With guided practice, these programs are designed to help you increase listening accuracy and memory.

Definition of Auditory training

The majority of the hearing impaired is not totally deaf. Very often they have remnants of hearing i.e. residual hearing as if the gates were slightly open. Making use of it and training the child to use this residual hearing is auditory training. Auditory training is the process by which children learn to recognize and understand auditory signals available to them Jill Bader (1999).

Numerous attempts have been made to define auditory training in the past. Though similar in some aspects, these definitions vary considerably according to the orientation of the definer and special considerations dictated by factors associated hearing loss, such as its degree and time of onset.

Goldstein (1939) worked primarily with deaf children and felt that auditory training involved a developmental and/ or improvement in the ability to discriminate various properties of speech & non speech signals. These properties include loudness, pitch, rhythm and inflection.

Auditory training is a set of procedures aimed at helping the aurally handicapped become more proficient in attending to the speech sounds, discriminating one from another and effecting on increase in retention of sounds. Kelly (1953).

Auditory training is meant to help people with hearing loss, improve their ability to interpret, process, and assimilate auditory input. Intervention can be provided individually or in group setting. Although group settings are valuable and desired to foster socialization and improved communication strategies and behaviors, it can sometimes be difficult to meet the individual auditory training needs of the group members. For this reason, Auditory training intervention is best served on a one to onebasis with program designed with individual requirement considered. Its most common use is with children with prelingual sensorineural-impairment, especially those with moderate to profound degree of loss with congenital onset. Another targeted population for auditory training in recent times has been cochlear implant recipients, both children and adults. There is strong evidence that a structured program of listening training enhances the benefits derived from cochlear implant.

Importance of Auditory Training

Because hearing loss will prevent perception of some of the acoustic cues in speech, affected children ordinarily require an increased quantity of input to attempt partially exposure to secondary but still salient acoustic ones in speech signal will permit such children to learn to take advantage of them. For most of the hearing impaired one can take no more effective measure with regard to minimizing an auditory based linguistic system than to employ a child’s innate biological capacity as the most potential. Most hearing-impaired individuals and hearing aid users’ brain receive incoming acoustics signals that are, to some degree, different, and presumably inferior, to that which the individual with normal hearing receives. Another reason is that hearing and listening are quite different and listening is a learned behavior which develops as a result of the search for meaning. Hearing requires audibility, but for a good listener, the listener must integrate a number of skills including attention, understanding, and remembering. Patients presenting similar audiometric profiles often obtain very different benefits from amplification.

Auditory Training programs train the brain in three key areas:

- Auditory working memory: our ability to keep words in short-term memory so the meaning of the word and its linguistic context can be processed.

- Auditory processing speed: our ability to recognize speech quickly, which is important during everyday conversation, where one word follows another in rapid succession.

- Auditory attention: our ability to extract meaningful speech from a background of competing background noise, as might be required to do when trying to listen in a noisy restaurant.

Auditory training is also referred to as “aural rehabilitation” and “hearing exercises”. The goal of auditory training is to help improve working memory and increase auditory processing speed. Hearing aid users who practiced auditory training, specifically hearing speech against background noise, for 3 hours a week were able to correctly identify 25% more words in sentences than when they started. It may be time to consider auditory training if any of the following applies when also wearing devices:

1. You are still avoiding noisy restaurants

2. You are asking family members to repeat themselves more often

3. Feeling fatigued after a conversation or being in a noisy listening environment

Analytic training

In this the listener attention is focused on segments of the speech signal, such as syllables or phonemes. More emphasis is placed on utilizing acoustic cues, such as the presence or absence of voicing in the words coat and goat than on gaining meaning from the speech signal. Presumably, one’s ability to recognize these segments in isolation will carry over to real-word communication tasks, allowing them to recognize connected discourse better.

Synthetic training.

During this training, individuals learn to recognize the meaning of an utterance, even if they do not recognize every sound or word. They don not perform an analysis of the signal on a sound-by-sound or syllable-by-syllable basis.

There is no clear cut dichotomy between analytic and synthetic training; rather, this is a continuum, and listening activities will gravitate from focusing attention on understanding the gist of a message. In the same lesson, a student might perform analytic training activities and then switch to synthetic activities.

The more current approaches to auditory training vary considerably. According to Blamey and Alcantara (1994), it is possible to categorize them into one of four general categories, based on the fundamental strategy stressed in the therapy: Analytic, Synthetic, Pragmatic and Eclectic.

Pragmatic training includes the listener being instructed about how to get information which will be important for communication this is done by changing the circumstances in which the interaction takes place. The most important factor in this is to develop the residual hearing skills. Factors that a listener with a hearing loss can control includes level of signal which can be adjusted between the distance of the speaker and listener,Signal to noise ratio can be increased by moving close to the speaker or moving away from noisy area to a more quieter location and context and the complexity of message can be controlled by asking questions and using appropriate repair strategies.

Eclectic training includes that combines most or all of the strategies previously described.While the auditory training programs to be described all have analytic, synthetic, or pragmatic tendencies, most would best be described as eclectic, since more than one general strategy for the training of listening skills typically is used with a given child or adult.

Individual attention not the only method of dealing with the problems of the hearing handicapped. Auditory training administered in a group situation can help the Hard-of-hearing (H-O-H) achieve goals through working with others. Group training has along and learning takes place. In schools and various training institutions throughout the country, classes are becoming larger and larger as these institutions attempt to answer the demand of society to educate more and more students. Group work is not peculiar to teaching & learning situations, but has been found useful in psychotherapy.Group Auditory training has some of the characteristics of a teaching-learning classroom situation. Also, it is often similar to the group psychotherapy session.

Methods and Exercise

Teaching methods for auditory learners have evolved with time. Lip reading training has improvised to various forms of auditory verbal training. There are various ways by which teaching methods for auditory learners can be imparted:

- Individually: requires an expenditure on resources and is quite inaccessible due to lack of awareness.

- In groups: not demanding as regards the time and expenditure involved.

- At home: can be done individually or in groups.

Auditory training approaches:

1. Wedenberg’s Approach (Wedenberg 1951):

It is an early approach to auditory training, used with children with severe to profound hearing loss. It was first described by Wedenberg.

His training also served to exploit whatever residual hearing a child possesses. His approach was eventually labeled as unisensory, since he advocated that speech reading should not be consciously emphasized until the child developed a proper listening attitude.

His program was directed towards increasing the child’s attention to the sound. Both environmental and speech sounds were used in the early stages, which he referred to as“ad concham amplification”. This involved speaking directly into the child’s ear at a close range (1/2 inches) rather than the child use hearing aids.

Exercises, which helped the child become aware of and attend to sound at increasing distances, were used. These included presentation in isolation vowels and voiced consonants whose formants were thought to be within the child’s (with hearing impairment) audible range.

Syllables were used in a variety of formal therapeutic activities, as well as informal settings at home. Combining individual vowels and consonants learned in isolation resulted in perception of a limited number of words. At this time Wedenberg advocate part time use of hearing aid.

Later, training progresses to short sentences formed by words already recognized by the child acoustically. Although not given direct focus, speech reading could be used as a supplement.

His method was directed towards development of auditory, speech and language skills in children with either a congenital or prelinguistic hearing loss of severe to profound proportion.

2. Verbotonal (Peter Guberina, 1952):

A novel approach toward delivering amplified sound to HI listeners has been proposed, called the verbotonal method (Guberina, 1964).

The verbotonal method is designed to develop auditory perception and speech production through the special amplification equipment, tactual stimulation delivered by a bone conduction vibrator and body movements calculated to produce varying degrees of muscular tension associated with the production of speech sounds.

It’s effective for establishing good spoken language and listening skills. Based on a developmental model of normal hearing children.

The verbotonal method is based on the theory that amplification of the frequencies at which HI is greatest results in added distortion of the auditory signals and should be avoided.

Guberina advocates the use of a special auditory training unit (SUVAG II) composed of banks of filters that can deliver selected bands of frequencies from 20-20000 Hz.

She hypothesized that each person has an ‘optimal band of frequencies’ through which auditory information is least distorted, this frequency band usually corresponds to that frequency region in which hearing is best.

SUVAG II is adjusted to pass only the optimal field of hearing, determined for each child individually by presenting filtered and unfiltered nonsense syllables for detection or identification.

He believes that amplification of auditory cues below 500 Hz to include rhythmic patterns and sound fundamentals can help hearing impaired to perceive higher speech frequencies.

Because most SNHL is greatest in the HF, the verbotonal method stresses delivery of LF amplification, auditorily their earphones and tactually through a small vibrator held in the hand.

In addition to the auditory tactual stimulation kinesthetic movements are associated with each speech sound and used by teacher and children during speech.

In early stages of verbotonal training, nonsense syllables or single words are used exclusively as auditory stimuli.

Accurate imitation by the child, including normal vocal pitch, is the criterion for success.

The verbotonal method confines AT to perception and imitation of speech, represented by nonsense syllables, words and sentences.

Guberina advocates the verbotonal method for all ages and types of deafness, congenital or advantageous regardless of the degree of hearing loss.

3. Acupedic approach

This is a unisensory approach where the term was coined by Dr. Henkandhas been advocated by Dorin Pollack in 1952. The term ‘acu’ refers to acoustic and ‘pedi’ refers to pediatrics. This approach is not only to teach listening skills but also teaches language.

Principle: Early training using audition only, avoidance of lip reading and other cues, anduse of normal speech pattern.

Dorin Pollack has described the pre-requisites and steps to be carried out for this approach. The pre-requisites are:

– Early Identification of hearing impairment preferably by 1st

– Fitting binaural ear devices (recommended for those with profound hearing loss).

– Training through one modality, that is, auditory modality.

– Normal contact with the environment.

– Prolonged systematic training which is intensive.

This kind of training can be given to children who even have profound hearing loss according to them, children up till 5 years can be given the training but not above 7 years of age.

Pollack has mentioned the following steps to be taken in order to carry out the method:

Auditory Training:

– Awareness of sounds-initially loud sounds and later softer sounds.

– Attending to sounds.

– Responding to sounds.

– Discrimination between sounds.

– Developing feedback mechanism.

Do not use speech reading or lip-reading:

– Reason she recommends this that eye cannot detect rhythm and other suprasegmental aspects of speech.

– Eye does not provide adequate feedback about the way person produces speech himself/herself.

– People who speech read are much tensed, because the person has to strain a lot to speech read. Proprioceptive feedback cannot replace auditory feedback. One gets feedback about position, movement etc.

– Using normal speech patterns and everything should be taught meaningfully.

– Language develops through imitation.

– Articulation is taught later on. All of these training is through individualized training program and not in group session.

Advantages of Acupedic approach:

– Children learn to use their auditory mechanism to their maximum.

– They learn vocabulary and language more easily.

– Voice quality of person is much better,

– Articulation tends to get better.

– Children who learn speech and language earlier would be able to integrate with others and then find employment later.

One of the earliest approaches in listening training which gives systematic steps was given by Carhart in 1960. It includes both childhood and adulthood procedures.

Carhart’s auditory training program for prelingually impaired children was based on his belief that since listening skills are normally learned early in life, the child possessing a serious HL at birth or soon after will not move through the normal development stages important in acquiring these skills. Likewise, when a hearing loss occurs in later childhood or in adulthood, some of the person’s auditory skills may become impaired even though they were intact prior to the onset of the hearing loss. In each instance, Carhart believed that auditory training was warranted.

Childhood Procedures: Carhart outlined 4 major steps or objectives involved in auditory training for children with prelingual deafness. They are:

– Development of awareness of sound: The child has to recognize when a sound is present and attend to it. The child should be surrounded with sounds that are related to daily activities and that are clearly audible.

– Development of gross discrimination: Initially involves demonstrating with various noisemakers that sounds differ. Training at this level involves discrimination of several parameters of sound, such as frequency, intensity (loud versus soft) durational (long versus low) properties of sound. When the child is able to recognize the presence of sound and can perceive gross difference with non-verbal stimuli, then move on to the next step of gross discrimination for speech sounds.

– Development of broad discrimination among simple speech patterns:By now the child is aware that the sound differs and is ready to apply this knowledge to the understanding of speech. Familiar meaningful phrases that is sufficiently different to minimize confusion.

– Development of finer discrimination for speech: Fine discriminations of speech stimuli in connected discourse and integrating an increased vocabulary to enable him or her to follow connected speech in a more rapid and accurate fashion.

Carhart also felt that the use of vision by the child should be encouraged in most auditory training activities.

Adult Procedures: He recommended that auditory training with adults focus on reeducating a skill diminished as a consequence of the hearing impairment.

This approach establish “an attitude of critical listening” which involves being attentive to the subtle differences among sounds and can involve analytic drill work on the perception of phonemes that are difficult for the adult with HI.

Lists of matched syllable and words that contain the troublesome phonemes, such as she- fee, so –tho, met- let, or mash-math, are read to the individual, who repeats them back. It also includes phrases and sentences. Speech reading combined with person’s hearing was also encouraged during a portion of the auditory training sessions.

Carhart advocated the auditory training sessions to be conducted in 3 commonly encountered situations:

– Relatively intense background noise

– Presence of competing speech signal

– Listening on the telephone

According to Carhart, the use of hearing aids is vital in AT, and he recommended that they be utilized as early as possible in the AT program. These recommendations were consistent with Carhart’s belief that systematic exposure to sound during AT was an ideal means of allowing a person to adequately adjust to hearing aids and assist in using them as optimally as possible.

In this approach focus is more on auditory training than auditory learning.

Auditory Training-mainly drill work with or without involving concept i.e. may be meaningful or non-meaningful.Auditory Learning– it is done meaningfully. So, in a real life situation, person is required to listen not only to verbal but also non-verbal. They do require getting information about both and needing both sides of the hemisphere to be stimulated.

4. Erber (1982):

A flexible and widely used approach to auditory training designed primarily for use with children has been described by Erber (1982). This adaptive method is based on a careful analysis of a child’s auditory perceptual abilities through the use of the GASP (Glendonald Auditory Screening Procedure) assessment battery.

The GASP’s approach to evaluate a child’s auditory perceptual skills takes into account two major factors:

– The complexity of the speech stimuli to be perceived (ranging from individual speech elements to connected discourse)

– The form of the response required from the child (detection, discrimination, identification, or comprehension).

Erber’s emphasis on integrating the development of auditory skills into all activities with children with hearing impairment is shared by many, including Sanders (1993) and Ling and Ling (1978), who recommend that auditory training “be viewed as a supplement to auditory experience and as an integral part of language and speech training”. Thus, therapy directed towards development of auditory and language skills can and should be done in an integrated, mostly seamless manner.

5 Developmental Approach to Successful Listening II (DASL-II):

Stout and Windle (1994) have developed a sequential, highly structured auditory-training program called Developmental Approach to Successful Listening II or DASL-II. Like Erber’s (1982) approach, the DASL II consists of hierarchy of listening skills that are worked on in relatively brief, individualized sessions.

The DASL II curriculum can be used with persons of any age, but mainly has been utilized with preschool and school-age youngsters using either hearing aids or cochlear implants. Three specific areas of auditory skill development are focused on:

– Sound awareness: deals with the development of the basic skills of listening for both environmental and speech sounds. The care/use of hearing aids and cochlear implants are also included.

– Phonetic listening: includes exposure to fundamental aspects of speech perception such as duration, intensity, pitch and rate of speech. The discrimination and identification of vowels and consonants in isolation and in words are included in this area.

– Auditory comprehension: emphasizes the understanding of spoken language by the child with hearing impairment. Includes a wide range of auditory processing activities from basic discrimination of common words to comprehension of complex verbal messages in unstructured situations.

As with GASP approach, information from the DASL II placement test enables the clinician to determine the appropriate placement of the child within the auditory skills curriculum. The test’s developers provided numerous activity suggestions for the clinician. These address each of the many sub-skills of the three main areas of listening which make up DASL II. These are organized from the simplest to the most difficult listening task.

A team approach is encouraged with DASL II, with the audiologist, speech-language pathologist, classroom teacher and parents working in a coordinated fashion on relevant subskills. This makes it vital that frequent communication occurs among the team members.

6. SKI-HI:

Clark and Watkins (1985) developed this comprehensive identification and intervention treatment program for infants with hearing impairment and their families, and it is in wide use. One of the major components of SKI-HI’s treatment plan is a developmentally based auditory stimulation-training program. It is utilized in conjunction with language-speech stimulation and consists of 4 phases and 11 general skills as shown in Table 2.

|

PHASES |

SKILLS |

|

Phase I (4-7 months) |

Attending:child aware of presence of home and/or speech sounds but may not know meanings; stops, listens, etc. Early vocalizing: child coos, gurgles, repeats syllables, etc. |

|

Phase II (5-16 months) |

Recognizing:child knows meaning of home and/or speech sounds but may not be able to locate; smiles when hears Daddy come, etc. Locating: child turns to, points to, locates sound sources. Vocalizing with inflection: high/low, loud/soft, and/or, up/down. |

|

Phase III (9-14 months) |

Hearing at distances and levels: child locates sounds far away and/or above and below. Producing some vowels and consonants. |

|

Phase IV (12-18 months) |

Environmental discrimination and comprehension: child hears differences among and/or understands some sounds. Vocal discrimination and comprehension: child hears differences (a) among vocal sounds, (b) among words, or (c) among phrases and/or understands them. Speech sound discrimination and comprehension: child hears differences among and/or understands distinct speech sounds. Speech use: child imitates and/or uses speech meaningfully. |

Table 2. The four phases and eleven skills of the SKI-HI auditory program

The approximate time line indicates the estimated amount of time spent by a profoundly deaf infant in each phase.

Although these phases and skills are organized developmentally, infants may not always move sequentially from one phase or skill on the list to the next higher one in a completely predictable manner. SKI-HI provides an extensive description of activities which the clinician and parent or caregiver may utilize in working on sub-skills related to each of the specific general skills included in each phase of the auditory training program.

7. Traditional approach:

Hirsh and Ling(1976) have described 4 levels of audition that contribute to the perception of conversational speech, detection, discrimination, identification and comprehension.

– Detection: requires only the child should be able to distinguish between the presence and absence of sound

– Discrimination: involves differentiation of speech sounds.

– Identification: requires the child to recognize the speech signal and to be able to identify.

– Comprehension: involves understanding of the message on a cognitive and linguistic basis.

The first 2 stages are not usually done. The suprasegmental part is not included here; it taps only long term memory. Mastery of the lower levels of detection and discrimination is considered to be the pre requisite for successful performance at the higher level of identification and comprehension.

Children should progress through the four levels and the various stimulus complexities at their own rate and to the extent dictated by the status of their residual hearing. The detection level in the matrix does not correspond to the awareness stage as proposed by Carhart, because it focuses on speech reception rather than awareness of the sounds in general.

8. Ling’s approach:

Training programme is based on:

– Acoustic characteristic of speech

– Emphasis on listening aided by amplification

– Involves segments as well as supra segmental

– Recognizes need to attain vocal system, respiration, motor control and coordination. Prior to use of speech in meaningful contexts.

Ling emphasized that speech should be taught at phonetic level rather than phonological level. Child’s ability to detect all six sounds demonstrates that ability to detect all aspects of speech.

9. Speech tracking /continuous discourse tracing:

Developed by DeFilippon Scott (1978) to provide perception practice with sentence length material referred to tracking. It involves a clinician to read short segment of story in an auditory only communication mode.

The HI adults then attempts to repeat verbatim what was read. When the listeners failed to repeat, the clinician selects one or more of series of strategies to help the listener achieve 100% recognition.

Strategies include repeating the words missed, repeating the words heard correctly, and using the synonym for the word missed .Strategies are selected at the clinicians’ discretion. Visual cues can be added for bisensory training. Performance is monitored by calculating the number of words correctly repeated by the listener per minute during a therapy session.

Speech tracking requires that patient (receiver) listen to segment of on-going speech usually taken from a written passage, spoken by a communication partner (sender) and then repeat the utterance verbatim.This can apply to any sensory modality.

10. Topicon (Erber 1988):

In this activity the patient or clinician chooses a topic of interest from a prepared list. Then patient and clinician carryout the conversation. The clinician assesses the fluency of the conversation on the basis of a number of presented variables known to influence conversational fluency and satisfaction.

For example the amount of speaking time taken by each person involved in the conversation, no. of conversational turns and no. of communication breakdown. After the communication is completed the patient and clinician discuss the success of the conversation, identifies source of difficulty and identify possible solution that might be implemented to overcome those difficulties.

Other activities include:

– Viewing and analyzing specific segments of video taped conversations, identifying the global characteristics of the conversation and judging the level of satisfaction experienced by the participants.

– Conversation activities such as speech tracking procedures, question and answer activities and topic centered conversation can be used to improve the conversational fluency (Erber 1988, 1996).

11. SPICE:

Moog, Biedenstein, and Davidson (1995) developed the Speech Perception Instructional Curriculum and Evaluation (SPICE) to provide a guide for clinicians in evaluating and developing auditory skills in children with severe to profound hearing loss. It contains goals and objectives associated with four levels of speech perception. The first level detection,is intended to establish an awareness and responsiveness to speech. The second and third levels, suprasegmentaland vowel and consonant perception, are worked on. In suprasegmental section children work on differentiating speech based on gross variations in duration, stress, and intonation. In the vowel and consonant section, children begin to make perceptual distinctions among individual word stimuli with similar duration, stress, and intonation features, but with different vowels and consonants. With progress, the child is introduced to the fourth level, connected speech. Now the emphasis is the perception of words in a more natural environment (phrases and sentences). Activities for SPICE are done with combined auditory-visual presentation, as well as auditory-only listening situation. As the child progresses, the newly acquired skills can be refined further in more natural, informal conversation. Recently, SPICE has been used extensively with children using cochlear implants as an approach to developing listening skills in conjunction with their expanded auditory input.

12. Auditory Learning-learning to listen:

Over the years, a lot of terminologies have been used to enable the individuals to use their auditory mechanism for communication. Some of the terms that have been used include auditory training, listening training, and acoustic training. These three are used interchangeably and the most commonly used term is auditory training.

The other terms used include auditory learning. There are also other approaches that have been given specific terminologies such as auditory verbal therapy (AVT), auditory-oral method, and aural-oral method. So it is required these terms be defined.

Auditory learning: It is one in which activities for developing spoken language are related to the children real life experience and language stresses the comprehension of meaningful sounds which is considered to be highest level of auditory behavior (Erber, 1982; Sanders, 1982).

Auditory-oral method: It’s a method to teach language both receptive as well as expressive to children with hearing impairment. Some believe that along with the auditory cue speech reading can also be carried out.

Aural-oral method: It is a method where the child develops/ taught language through the auditory mechanism and communicates through speech.

Auditory training can be done at home with a program set up by your audiologist or completed through apps available on smartphones, tablets, and computers. These programs are designed to act like a game so it is interactive and fun to do. Examples of some apps are:

· AngelSound

· Soundscape

· Hear Coach

If downloading an app isn’t the user’s preference, other ideas for auditory training include listening to audiobooks and having practice conversations with family members.

2.3 Auditory Verbal Therapy: Principle, importance and role of teacher

Auditory Verbal therapy is a highly specialist early intervention family centred coaching programme which equips parents and care-givers with the tools to support the development of their deaf child’s speech and language development.

In order for deaf children to listen, they require optimum technology such as hearing aids or cochlear implants. They also need the technology to stimulate the listening part of the brain, the auditory cortex. Owing to neuroplasticity, the auditory cortex requires stimulation early in a child’s life, ideally before three and a half. Auditory Verbal programmes work to ensure optimum technology is provided and that parents are supported with strategies to stimulate listening and therefore the listening brain. As a result, children with hearing loss are better able to develop listening and spoken language skills, with the aim of giving them the same opportunities and an equal start in life as hearing children.

Through play-based therapy sessions, parents are supported with the tools – Auditory Verbal techniques and strategies – to develop their child’s listening and spoken language. Auditory Verbal therapy enables parents to help their child to make the best possible use of his or her hearing technology and equips parents to check and troubleshoot it in collaboration with their audiology team. This will maximise a child’s access to sound so that listening and spoken language skills can be developed to the fullest extent possible.

Through play-based sessions using the Auditory Verbal approach, the child develops a listening attitude so that paying attention to the sound around them becomes automatic. Hearing and listening become an integral part of communication, play, education and eventually work. All learning from the sessions carries over into daily life. This means that at home, parents can make everyday activities such as setting the table or reading a story into a fun listening and learning opportunity.

Definition of Audio Verbal Therapy

Auditory verbal therapy provides systematic instructions to hearing impaired children and their parents.

Auditory: Children who are deaf learn how to listen.

Verbal: Children who are deaf learn how to talk.

Therapy: Parent/caregiver attends one to one lessons with their child and learns how to teach their children in everyday situations.

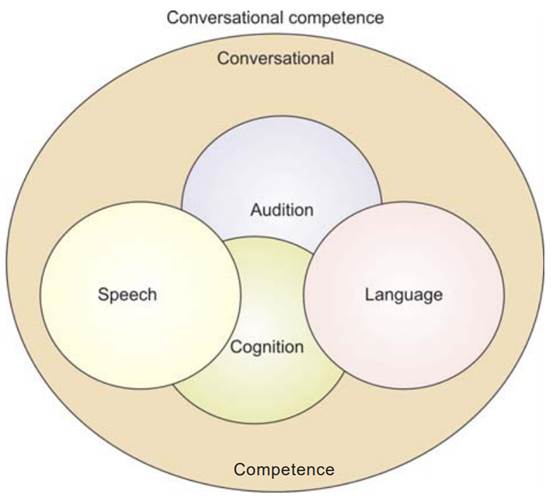

Auditory verbal therapy (AVT) is an early intervention approach for the children who are deaf or hard of hearing and are fitted with hearing devices in an early age. It is individualized therapy on one to one basis in a listening environment. The goals are set in four areas of development such as; audition language, speech and cognition. Parents are partners in this program focused to develop spoken language communication. AVT emphasises the development of listening and language through natural play, singing, daily routines as well as structured therapy activities. AVT focuses on education, guidance, family support and “rigorous application of techniques, strategies conditions and procedures that promote optimal acquisition of spoken language through listening”

THE GOALS OF AVT

The goal of auditory verbal practice is that children with hearing impairment can grow up in regular learning and living environments that enable them to become independent, participating and contributing citizens in mainstream society. The goals of AVT are for children to learn to listen and talk to engage in meaningful conversation, to be assimilated into regular school programs and to have educational, social and vocational choices throughout life. The goal of Auditory Verbal Therapy is to develop conversation and competency in children.

Principles of AVT

The main principles of the Auditory verbal therapy is as follows

· Use of one sensory channel i.e. Auditory ONLY (No lip reading).

· Detection of hearing impairment as early as possible.

· To ensure that medical and audiological management is thoroughly completed, including selection, modification and use and maintenance of appropriate hearing aid / Cochlear implant.

· To support children's auditory verbal development through One to One therapy.

· Family involvement must be present as they are the primary models for spoken language.

· To wear the aid ALL DAY EVERY DAY. Using natural sequential patterns of listening, speaking, spoken language and cognition to stimulate natural communication.

· To help children integrate listening into their development of communication and social skills. The ultimate goal is a well adjusted person who uses listening and speaking to successfully interact with other at home and school in the community and in the world.

· Ongoing evaluation of progress to ensure that the Auditory Verbal Approach is appropriate and through diagnostic intervention, modify the programme when needed.

· To help those children monitor their own voices and the voices of others in order to enhance the intelligibility of their spoken language.

· To provide support services to facilitate the children's Inclusion or integration into regular education classes.

The goal of all of the communication approaches is to give children with hearing loss of the skills and abilities to communicate with their peers. This, however, is not the only goal – these individuals, as adults, must become contributing members of society. That is, they must find employment and actively participate in their communities.

Auditory Verbal Therapy encourages the maximum use of hearing in order to learn language and stresses listening rather than matching. Young children with hearing impairment even with minimal amounts of amplified residual hearing can be taught to use. In this kind of therapy, children with hearing impairment can grow up in regular and learning environment.

Stages of Auditory development : -

Sound Awareness

· Association of Meaning to Sound

· Imitation and Expansion.

· Comprehension: Effective Responses to Language.

Role of a Teacher

A teacher of a child with hearing impairment is also a team member of the intervention process with Auditory verbal therapy method. Next to the parents a child with hearing impairment spends most of the time with his / her teacher. The special teacher may guide his/her student at the classroom, in their home or in different extracurricular activities. In Auditory Verbal therapy method the child has to listen with his amplification device and speak what he learns. Therefore, the teacher should follow the aural oral method of communication in the classroom and follows the principles of oralism during his / her class.

In the beginning of the classes the teacher should check the individual or the group hearing aid or the implant as the aid functions properly for the child. If there is problem in the aid he/ she should immediately refer them to the audiologist. The teacher should follow the recommendation of the audiologist or Speech Language pathologist for communication i.e. the teacher's advice will be always verbal. Not a single nonverbal cue will be given to child for their understanding. As such they should also counsel the parents as to communicate with the child verbally only. The teacher also guides the student's friends and peer group to talk orally among themselves.

The teacher may follow the following activities of the auditory verbal therapy in the classroom:

- At first presentation of auditory stimulus.

- Auditory attention: signal "listen"

- Provide uncluttered listening space

- Acoustic highlighting

- Use visual clarifiers

- Speak slowly

- Allow processing time

Those children with hearing impairment follow the instruction of the teacher, they can learn verbal language and can include in the mainstream society.

2.4 Auditory Training and AVT: Pre-requisites, challenges, similarities & differences

The basic principle of the Auditory Training and the Auditory Verbal therapy is same. As the child with hearing impairment must have to learn to listen auditorily and to speak orally only. In both training sessions the use of amplification devise is must.

For success in Auditory training and Auditory verbal therapy the child with hearing impairment must have the following prerequisites.

1. Early Identification: Early detection of hearing loss and early intervention of the disorder is must for Auditory training and auditory verbal therapy for the use of critical age period.

2. Proper Amplification Device: The child should use the proper hearing aid and or any other amplification device like cochlear Implant.

3. Adequate residual hearing: The child will learn to listen and speak through maximizing their residual hearing with amplification technology.

4. Parental cooperation: Parent participation is vital to the success of Auditory Verbal Therapy for two reasons: parents are the natural teachers of their child's language and the parents are always with their child so can be constantly encouraging language development.

5. Proper Audiological management- There should be good coordination among professionals of the Rehabilitation team with skilful therapist and parents.

6. Child's Intelligence and learning style.

7. Listening to speak: The child learns to speak through listening to natural sounding speech. Correct spoken models of language are crucial to teaching the child to monitor his/her vocalizations. Visual cues are not encouraged.

8. Assessment: Monitoring and evaluating the development of listening skills as an integral part of the development process.

9. Integration result: Appropriate amplification and Auditory-Verbal Therapy enables children with a hearing loss to develop auditory receptive skills (understanding language) in the short term that will translate via medium outcomes, such as attending mainstream school, into greater social independence and quality of life.

10. Presence of other prerequisites of normal speech and language development like i) Neuromotor Maturation, ii) Sensory Perceptual ability, iii) Physical and Emotional development, iv) Cognitive development and v) Communicative environment.

Factors affecting the success of Auditory training

Auditory training or any skills training involves systemized and directed practice. What a Hearing –Handicapped person learns through periods of auditory training is partly attributable to the length of time he practices and the knowledge and competence of the audiologist who has outlined and is managing the aural rehabilitation program.Success of auditory training involves factors such as:

Motivation: any progress will depend in large measure on the degree of willingness to accept auditory training as an important and worthwhile undertaking. This does not mean, however, that the highly motivated, hard-of –hearing person will show tremendous progress and one with low motivation will make no progress. They also report that hard-of –hearing show increased motivation when they are placed in competitive situations. This is one of the advantages of group therapy.

Intelligent cooperation with the clinician of those in close association with the Hearing Handicapped individual: it is of utmost importance that a realistic set of goals be outlined and understood by those who are near the person with HL, as well as by the handicapped individual. If this is accomplished and if those closest to the handicapped individual are kept informed of the aims of the program as it progresses, much good can result. Those who live with handicapped persons can provide opportunity for continued practice in the home and continued encouragement. Encouragement and understanding by others do not guarantee that the hearing-handicapped individual will maintain or increase his level of motivation, but they provide the kind of support that frequently determines whether or not an attempt at aural rehabilitation is successful. Time devoted to counseling the family of the hard-of –hearing person serves a valuable purpose.

Age of the client: Auditory training should be undertaken as soon as it is discovered that the hearing handicap cannot be reversed by medical or surgical intervention. This means that some youngsters who are one year old or even younger should receive training. At these early ages, habits of attending to sound are formed which essential to later are training involving discrimination among sounds. It is particularly important because it affects early oral language development. In other learning task the evidence indicates a decrement in accuracy and extent of learning as the individual progresses from maturity to “old” age.

Practice materials employed by the clinician: the practice materials suggested for AT are comprised of an aggregate of sounds, noises, and speech. From the standpoint of good training, practice materials should vary in many dimensions. A broad range of practice material willprovide exposure that is comparable to many situations in which the training will later be applied.

Establishment of proper habits by the clients: to ensure effective AT, the audiologists must make certain that the client develops certain habits that will increase his chances for success. Two items are particular importance: (1) the hard-of–hearing person must develop the habit of listening carefully to instructions given at the outset of each exercise and of asking for further instructions if he is not sure he has understood. (2) The hard-of-hearing person must be encouraged to check on the accuracy of his responses after each set of exercises.

Ability of the client to understand the tasks (principles involved): an important factor in learning is understanding the principles that support the task being performed. The audiologist should inform the handicapped individual, when possible, of the reasons for doing the tasks and of their underlying principles. These explanations should be simple enough to be clear and understandable to the handicapped person. An understanding of the general principles will enable the handicapped person to apply them to new tasks that have characteristics in common with the old.

Knowledge of progress: the literature on the psychology of learning generally is agreed that giving an immediate report of results to the subject after he has completed his task is of the utmost importance.

Auditory training as a set of procedures aimed at helping the aurally handicapped become more proficient in attending to the sounds of speech, discriminating one from the another and effecting on increase in retention of sounds ( Kelly 1953).

According to Alpiner 1978, Auditory training consists of three facets:

i) Discrimination of individual speech sounds

ii) Hearing aid Orientation.

iii) Improvement of tolerance levels.

Whereas Auditory-verbal therapy is a method for teaching deaf children to listen and speak using their residual hearing in addition to the constant use of amplification devices such as hearing aids, FM devices, and cochlear implants. Auditory-verbal therapy emphasizes speech and listening. Auditory verbal therapy enables deaf and hard of hearing children to participate fully in mainstream school and hearing society. It is apparent that there are no differences between Auditory Verbal Therapy and Auditory training, however if we really understand the principles of both training there is a considerable differences between the two.

Similarities

Both of these approaches have the following factors in common:

i) They aim to assist the hearing impaired child to communicate with their peers using spoken language.

ii) For either of these approaches to be successful, early identification of the hearing problem is essential.

iii) Once the problem is identified, therapy should begin as soon as possible.

iv) Hearing aids or cochlear implants are used to enhance residual hearing ability.

v) Both aim to develop spoken language as the most desirable means of living and learning in society at large.

vi) Both of the approaches exclude sign language.

vii) Both employ current technology and follow a number of similar clinical and educational programme.

Differences

There are, however significant differences in those approaches.

i) In the auditory-verbal approach, much of the focus is on speaking and sound production. The teacher uses different types of 'modeling' to show the child how to speak correctly. For example, a teacher may use the highlighting model to correct partially incorrect words or an Expansion model that fits in the gaps when a child skips a word or phrase.. But in the auditory-Training programme, the focus on listening is much more important.

ii) In the auditory verbal therapy, the family is intimately involved in the learning process, and at least one parent must attend therapy sessions so that they can learn how to continue the learning process at home. In this approach, the parent becomes the teacher. In the auditory training programme Audiologist guide the child and the parent how to listen, discriminate, identified and comprehend all the sounds of the environment.

iii) Acoustic conditions of the home are very favorable to Auditory verbal therapy. In auditory training ambient noise level should be less than speech signals because ambient noise degrades speech signal. .A clear speech is essential to learning.

iv) Auditory verbal therapy involves children in abundant intervention with normal hearing peers, but in auditory training it is not essentials.

v) Auditory verbal practice is to seek admission to regular school from the earliest possible stage. In auditory training child is trained to comprehend speech and other signals from the environment not only for trying to include or integrate in normal school but also to receive the alarming noise from the environment.

2.5 Speech Reading: Concept, importance, Pre-requisites, challenges and Role of teacher

Speech reading (or lip reading) is a building block that helps a child with hearing loss understand speech. The child watches the movements of a speaker’s mouth and face, and understands what the speaker is saying. About 40% of the sounds in the English language can be seen on the lips of a speaker in good conditions — such as a well-lit room where the child can see the speaker’s face. But some words can’t be read. For example: “bop”, “mop”, and “pop” look exactly alike when spoken. (You can see this for yourself in a mirror). A good speech reader might be able to see only 4 to 5 words in a 12-word sentence.

Children and adults often use speech reading in combination with other building blocks — such as auditory training (listening), cued speech, and others. But it can’t be successful alone. Babies will naturally begin using this building block if they can see the speaker’s mouth and face. But as a child gets older, he or she will still need some training to use this building block.

Sometimes, when talking with a person who is deaf or hard-of-hearing, people will exaggerate their mouth movements or talk very loudly. Exaggerated mouth movements and a loud voice can make speech reading very hard. It is important to talk in a normal way and look directly at your child’s face and make sure he or she is watching you.

Speech produces not only sounds but visible movements of the lips, tongue, and jaw of the speaker as well. These movements are called articulators of speech. Because of the physical constraints imposed by the muscles involved in the articulation of speech sounds, the same speech sounds are produced with a consistent pattern of physical movements and these movements are then associated with specific sounds. Speech reading is based on this principle, that many of the sounds produced during speech may be "seen" by paying attention to the articulators of speech.

Importance

Speech reading or Lip reading can be called as a silent mode of verbal communication. The purpose of Lip reading is to provide visual cues to aid in the perception of speech. Not only have the deaf persons, person with normal hearing also communicated with lip reading. Sometimes we try to take some verbal information from a distant person through speech reading and sometimes we hide the oral movements of speech for not to give secrete information to unwanted persons.

For the persons with hearing impairment Speech reading can be included in their total communication approach. As the deaf person get some verbal information through speech and some through speech reading. The degree to which persons with hearing impairment depend on vision for information is related to the extent of their hearing loss. According to Ross (1982), there is a world of difference between the persons who are deaf, who must communicate through visual mode i.e. speech reading and persons who are hard of hearing , who communicate 'primarily' through an auditory mode.

Preparation

- Position. Speech readers are asked to position themselves with their back to the light so as to see the speaker's face clearly.

- Relaxation. A relaxed atmosphere favors speech reading.

- Recollection of speech sounds. Speech readers are encouraged to watch the speaker's face closely and to try to recall how their voice sounded.

- Speech movement. They are also encouraged to pay attention to the movements made by the lips, tongue and jaw as the person speaks, so as to learn how to differentiate the articulators, some being more recognizable than others.

- Facial expression. The facial expression of speakers is very important in speech reading, as it conveys a lot of information about the topic and the speaker's mood and feelings.

- Gestures. Gestures such as nodding and pointing also provide a lot of clues about what the speaker is saying.

Prerequisites

The Prerequisites that affect Speech reading process usually fall into five general areas as related to the Speaker, Speech reader, Environment, the Signal or Code, and other factors.

a. SPEAKER

1. Familiarity of the Speaker: A positive correlation was shown to exist between speaker - listener familiarity over 80 years ago (Day et .al1928). Speech reading performance will be good when the speaker is familiar to the speech reader.

2. Facial expression, Gestures and Physical position: Facial expression gives the cues about the context and situations. Speakers who used appropriate facial expression, common gesture and who positioned themselves face to face or within a 45 degree angle of the listener facilitated communication for speech reading (Stone, Berger 1972, 1957).

3. Articulation or Lip movement: Speakers who were precise and not exaggerated articulation are the easiest for the speech reader to understand the message (Davis et. Al. 1972).

4. Rate of Speech: If the speaker's normal speaking rate exceed or reduced, the listener's visual reception capabilities or exaggerate speech production then it hampers comprehension.

5. Distraction: The speaker should avoid simultaneous oral activities such as chewing, smiling, yawning, sneezing etc. while convening with a hearing impaired person. The 'making effect' of these coincidental activities may complicate the speech reading task.

6. Gender: Berger (1977) suggested that male speech readers sometimes find difficulty with female speaker and vice versa. Gender related variables such as moustaches or the use of lipstick may influence speech reading process.

7. Extent of Image: Impression or the image of the speaker on the speech reader also plays an important role in speech reading.

8. Associated Body movements: Nitchie (1972) suggested that speech reading will be more productive where the speech reader can observe appropriate nonverbal communication modes like head and body movements of the speaker.

9. Language spoken: Familiarity of language is an independent variable that influences the interpretation of visual cues. Language spoken by the speaker should be common or familiar to the speech reader.

10. Others like suprasegmental aspects of speech, speakers presentation and style etc. may influence speech reading.

B. SPEECH READER

1. Hearing capacity: Persons with significant amount of residual hearing have the potential to speech more successfully than those with very limited hearing due to availability of auditory cues contained in speech. Other factors like auditory perception abilities, age of onset of hearing loss, progressively, site of lesion etc. may influence speech reading.

2. Age and Language skills: Speech reading proficiency tends to develop and improve throughout childhood and early adulthood and appears to be closely associated with the emergence of language skills (Berger et. Al.1978). Even though the speech reading abilities are not fully developed in younger children, they may use speech reading to some extent even infants also. Other individuals do less speech reading than their counterparts who are between the age ranges of 21 to 30, may be due to decreased visual acuity with aging.

3. Intelligence: Much reduced intelligence level may result in poor speech reading performance (Smith et. al.1964)

4. Personality traits: Highly motivated clients tend to speech read more effectively than to unmotivated clients.

5. Visual performance proficiency:

a) Visual acuity: Even slight visual acuity problem had an appreciable negative effect on speech reading scores. Visual acuity must be at least 20 / 30 to enable the speech reader to see the five sequential articulatory movements of speech.

b) Visual problem: Like color blindness may affect speech reading through "Eye glass speech reading aid'.

c) Visual Memory: The speech reader must follow the following sequential pattern for visual memory.

i) Perception of the articulatory patterns from the speaker's mouth and jaw movements,

ii) Retention of the patterns sequentially in short term memory.

iii) Coding into linguistic units by using inner language coding system.

iv) Synthesize the information in permanent memory for final message identification.

v) Match with information in permanent memory for final message identification.

d. Visual perception of consonant and vowels: The visual perception of place of articulation of consonants, vowels and diphthongs is very important to speech reading.

6. Synthetic ability of the Speech Reader: Perceptual closure i.e the ability to identifying the patterns of speech and the conceptual closure i.e the ability to identify the message are the two synthetic abilities which requires speech reading.

7. Flexibility and Emotional attitude: It includes cooperation of parents, educational and therapeutic management etc.

8. Type of Intervention: Speech reading performance improves with cochlear implant / tactile devices as compared to conventional hearing aid or without hearing aid.

9. Motivation: Better speech reading skill was found among children who reported a positive attitude towards speech and speech reading by their parents and deaf peers. Interest and motivation should strengthen speech reading and overall communication skills.

C. ENVIRONMENT:

1. Distance and viewing angle: Speech reading ability is optional when the speaker is about 5 feet distance from the speech reader with face to face conversational situation. For most speech readers, watching the speaker at horizontal viewing angle of 0-45 degree is preferable.

2. Competition: simultaneous auditory and visual competition can have an adverse effect on speech reading under certain condition.

3. Light and Illumination: For most optimal speech reading, light and illumination should provide a contrast between the background and the speaker's face.

4. Cues: Speech reading ability increases when the speech is accompanied by pictorial, auditory, contextual, situational and environmental clues.

5. Coping up with the situation: The speech reader's ability to visually scan and cope up the situation and understand the speaker's role will provide an attention which is set for social or formal communication.

6. Auditory distractions: The effect of noise on speech perception by the hearing and hearing impaired participants and the person with hearing impairment ability to monitor his or her vocal modules in noise are also factors to be considered.

7. Visual Distraction: It also affects speech reading by drawing the speech reader's attention away from the force especially if the distraction is more interesting that the speaker.

Methods to teach speechreading:

The first inclination in education is to improve speechreading in order to improve outcomes. Therefore teaching methods are mentioned below:

- The Analytic approach focuses on the smallest units of speech to understand spoken communication. It is a bottom-up approach that concentrates on the details of the sounds – learning to recognize how they look on the lips and practicing their recognition in isolation and in single words. As mentioned above, it is very difficult to build the message from the sum of its parts and the use of this approach exclusively can be a frustrating and cumbersome experience for persons with hearing loss, with lower chances for success in everyday situations.

- The Synthetic approach is a top-down approach, where the perception of the the overall meaning of the message is emphasized more than concentrating on smaller parts. Common exercises focus on giving the speechreader some clues such as key words or a topic that will be discussed, presenting the message and having the speechreader respond to what he thought was said. The goal is to use context and any known information to allow for educated guessing, when parts of spoken information are missed. Limitations include situations when a speechreader is unable to determine the context of the message or unknowingly misinterprets the information, leading to misunderstanding.

Although these approaches may be a limited way to teach ‘lipreading’ or use of context, they have little evidence to support extensive instruction. Individuals naturally vary in how much speechreading benefits their understanding of speech in everyday situations. A bottom-up approach does not really improve this natural ability and a top-down approach may improve understanding in predictable situations with known vocabulary and topics, but is certainly not enough to improve performance in a dynamic educational environment teaching new concepts using previously unheard vocabulary.

Challenges of Speech reading

If a student has challenges hearing everything in class then encouraging him or her to speechread will help understanding, right? Not necessarily.

One study had typically hearing students answer comprehension questions about a story that was presented in a lecture format or when parts of the story were presented from locations around the student, to simulate listening to classroom discussion. The first finding was that accuracy when repeating sentences in quiet or noise (like on a Functional Listening Evaluation) does not predict the true impact of classroom acoustics on listening comprehension for lecture or discussion. In all cases, listening to lecture yielded higher comprehension than listening to discussion. For example, children who achieved a 95% accuracy repeating sentences in a typical classroom listening environment (+7 S/N noise, 0.6s reverberation) had poorer comprehension under more typical classroom lecture or discussion activities. Average results for 11-year olds when listening to lecture was 80% accuracy and 75% for discussion, whereas for 8-year-olds it was 40% and 33% respectively. If the noise level was improved (from +7 S/N to +10 S/N) the scores for understanding class discussion improved from 33%/75% to 60%/90% for 8/11 year-olds respectively.

This study further found that the younger participants (age 8) looked around more to aid their understanding during discussion. Most often these students were unable to visually keep up as the discussion moved from student to student. Furthermore, it appeared as though the act of trying to visually track class discussions could actually use up more cognitive resources, resulting in reduced comprehension, especially for younger students.

Additional research studies on persons with typical hearing found that considerable listening effort is required when listening at noise levels typical of the school classroom. In low noise, being able to watch the speaker improves speech understanding and reduces listening effort. Listening in high noise while watching the speaker results in greater effort to understand speech. Listeners who are better speechreaders benefit more from visual cues than those that are naturally poorer speechreaders.

There are many variables which may influence or challenge the Speech reading. These are:

1. Amount of Self teaching: speech reading does not always have to be taught, though the individual's skill can be improved through instructions. Numerous hearing impaired individuals have developed a fair degree of proficiency without formal instructions.