HOWARD GARDNER'S THEORY OF MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES

The theory of multiple intelligences was developed in 1983 by Dr. Howard Gardner, professor of education at Harvard University. This theory suggests that traditional psychometric views of intelligence are too limited. Gardner first outlined his theory in his 1983 book Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, where he suggested that all people have different kinds of "intelligences."

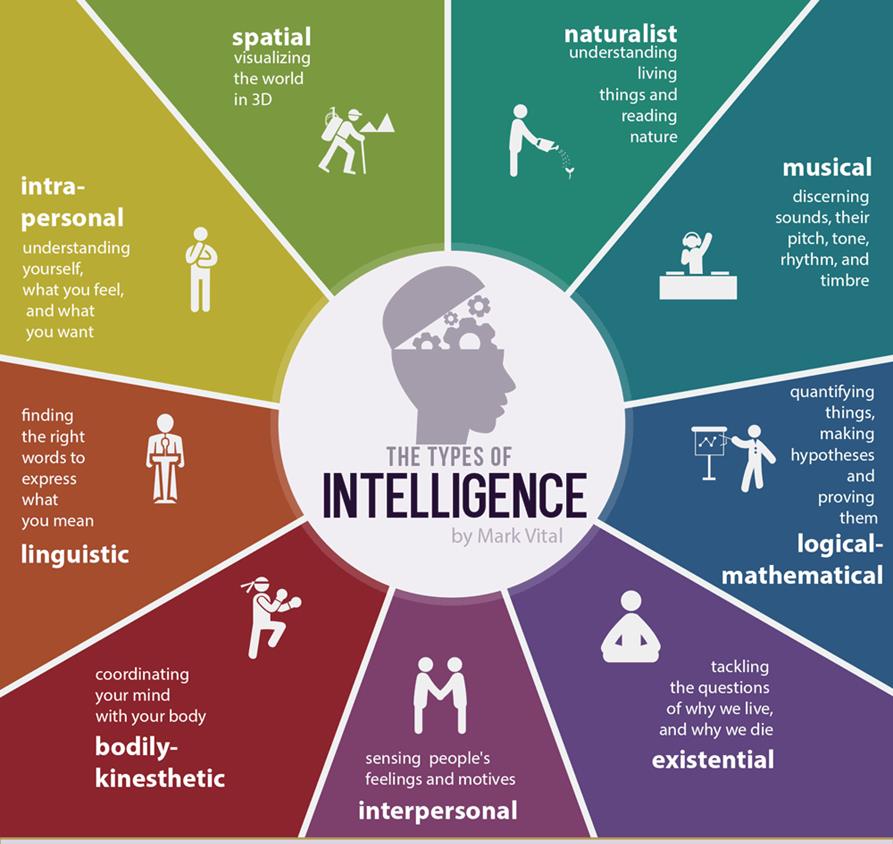

These intelligences are:

1. Verbal-linguistic intelligence (well-developed verbal skills and sensitivity to the sounds, meanings and rhythms of words): The ability to express oneself using words and language is known as verbal-linguistic intelligence. This intelligence is unique because it is the most commonly shared human ability. It allows us to apply meaning to words and express appreciation for complex phrases. Through reading, writing and sharing stories orally, we are able to marvel at our use of language. We see examples of this skill in journalists, poets, and public speakers.

2. Logical-mathematical intelligence (ability to think conceptually and abstractly, and capacity to discern logical and numerical patterns): Sometimes misconstrued as simply the ability to calculate mathematical equations, logical-mathematical intelligence is much more than that. Individuals with this developed intelligence demonstrate excellent reasoning skills, abstract thought, and the ability to infer based on patterns. They are able to make connections based on their prior knowledge and are drawn to categorization, patterning, and relationships between ideas. With experiments and strategy games as two coveted activities, it would make sense that possible careers would include a scientist, a mathematician, and a detective.

3. Spatial-visual intelligence (capacity to think in images and pictures, to visualize accurately and abstractly): Visually artistic people are known to demonstrate spatial intelligence. These abilities include manipulating images, graphic skills, and spatial reasoning – anything that would include more than two dimensions. They may be daydreamers or like to draw in their spare time, but also show an interest in puzzles or mazes. Careers directly linked to spatial intelligence include many artistic vocations, for example, painters, architects or sculptors, as well as careers that require the ability to visualize, such as pilots or sailors.

4. Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence (ability to control one’s body movements and to handle objects skillfully): The ability to manipulate both the body and objects with a keen sense of timing is known as bodily-kinesthetic intelligence. These people are able to accurately manipulate objects due to a strong mind-body union. This can be demonstrated in the form of physical skills, for example, athletes and dancers, or in precision and steady movement, such as surgeons and crafts people.

5. Musical intelligences (ability to produce and appreciate rhythm, pitch and timber): The ability to acutely reflect on sounds is demonstrated by those who possess musical intelligence. These people are able to distinguish between specific pitches, tones and rhythms that other may miss. Someone with musical intelligence is often a sensitive listener, and can reflect or reproduce music quite accurately. Musicians, conductors, composers, and vocalists all demonstrate keen musical intelligence. As young adults, we can witness these people humming or drumming to a self-directed rhythm. Musical intelligence is also closely related to mathematical intelligence, as they share a similar thinking process.

6. Interpersonal intelligence (capacity to detect and respond appropriately to the moods, motivations and desires of others): While the ability to communicate effectively with others is common knowledge on the basis of interpersonal intelligence, it is not merely limited to verbal interactions. People with developed interpersonal intelligence are also able to read the moods of others. Sensitivity to temperaments and the ability to communicate nonverbally allow these individuals to understand differences in perspectives. Because they can often accurately assess the sentiments and motivations of others, these individuals make good social workers, teachers, and actors.

7. Intrapersonal (capacity to be self-aware and in tune with inner feelings, values, beliefs and thinking processes): The ability to understand one’s own thoughts is known as intrapersonal intelligence. Individuals who demonstrate intrapersonal intelligence are acutely aware of their feelings and can show an appreciation for themselves and other humans. Often misconstrued as “shy,” these people are actually self-motivated and able to use their understanding to direct the course of their own lives. Philosophers, psychologists and religious leaders may all show high levels of intrapersonal intelligence.

8. Naturalist intelligence (ability to recognize and categorize plants, animals and other objects in nature): A sensitivity to features in the natural world is most closely tied to what is called naturalist intelligence. The ability to distinguish between living and non-living things was notably more valuable in the past when humans were often farmers, hunters or gatherers. Nowadays, this intelligence has evolved to more modern-day roles such as a chef or a botanist. We still carry traces of naturalist intelligence, some more so than others, which is evident by our preferences for certain brands over others.

9. Existential intelligence (sensitivity and capacity to tackle deep questions about human existence such as, “What is the meaning of life? Why do we die? How did we get here?”: The ability to be able to have deep discussions about the meaning of life and human existence is known as existential intelligence. People with this intelligence are sensitive but can rationally address difficult questions, for example, how we got here and why everyone eventually dies.

Gardner (2013) asserts that regardless of which subject you teach—“the arts, the sciences, history, or math”—you should present learning materials in multiple ways. Gardner goes on to point out that anything you are deeply familiar with “you can describe and convey … in several ways. We teachers discover that sometimes our own mastery of a topic is tenuous, when a student asks us to convey the knowledge in another way and we are stumped.” Thus, conveying information in multiple ways not only helps students learn the material, it also helps educators increase and reinforce our mastery of the content.

Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory can be used for curriculum development, planning instruction, selection of course activities, and related assessment strategies. Gardner points out that everyone has strengths and weaknesses in various intelligences, which is why educators should decide how best to present course material given the subject-matter and individual class of students. Indeed, instruction designed to help students learn material in multiple ways can trigger their confidence to develop areas in which they are not as strong. In the end, students’ learning is enhanced when instruction includes a range of meaningful and appropriate methods, activities, and assessments.

Multiple Intelligences are Not Learning Styles

While Gardner’s MI have been conflated with “learning styles,” Gardner himself denies that they are one in the same. The problem Gardner has expressed with the idea of “learning styles” is that the concept is ill defined and there “is not persuasive evidence that the learning style analysis produces more effective outcomes than a ‘one size fits all approach’” (as cited in Strauss, 2013). As former Assistant Director of Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching Nancy Chick (n.d.) pointed out, “Despite the popularity of learning styles and inventories such as the VARK, it’s important to know that there is no evidence to support the idea that matching activities to one’s learning style improves learning.” One tip Gardner offers educators is to “pluralize your teaching,” in other words to teach in multiple ways to help students learn, to “convey what it means to understand something well,” and to demonstrate your own understanding. He also recommends we “drop the term ‘styles.’ It will confuse others and it won’t help either you or your students” (as cited in Strauss, 2013).

The Difference Between Multiple Intelligences and Learning Styles

One common misconception about multiple intelligences is that it means the same thing as learning styles. Instead, multiple intelligences represents different intellectual abilities. Learning styles, according to Howard Gardner, are the ways in which an individual approaches a range of tasks. They have been categorized in a number of different ways -- visual, auditory, and kinesthetic, impulsive and reflective, right brain and left brain, etc. Gardner argues that the idea of learning styles does not contain clear criteria for how one would define a learning style, where the style comes, and how it can be recognized and assessed. He phrases the idea of learning styles as "a hypothesis of how an individual approaches a range of materials."

Everyone has all eight types of the intelligences listed above at varying levels of aptitude -- perhaps even more that are still undiscovered -- and all learning experiences do not have to relate to a person's strongest area of intelligence. For example, if someone is skilled at learning new languages, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they prefer to learn through lectures. Someone with high visual-spatial intelligence, such as a skilled painter, may still benefit from using rhymes to remember information. Learning is fluid and complex, and it’s important to avoid labeling students as one type of learner. As Gardner states, "When one has a thorough understanding of a topic, one can typically think of it in several ways."

Criticism

Gardner’s theory has come under criticism from both psychologists and educators. These critics argue that Gardner’s definition of intelligence is too broad and that his eight different "intelligences" simply represent talents, personality traits, and abilities. Gardner’s theory also suffers from a lack of supporting empirical research.

Despite this, the theory of multiple intelligences enjoys considerable popularity with educators. Many teachers utilize multiple intelligences in their teaching philosophies and work to integrate Gardner’s theory into the classroom.