Unit 2: Family and disability

2.1 Stages of reaction and impact and coping of having a child with disability.

2.2 Involving parents in diagnosis, fitment of aids and acceptance of disability by family.

2.3 Importance of family involvement and advocacy in interventional practices.

2.4 Concept, components and strategies of family empowerment.

2.5 Partnering for interventional practices.

2.1 Stages of reaction and impact and coping of having a child with disability.

Having a family member with an intellectual disability can have an effect on the entire family; the parents, siblings, and extended family members. It is a unique shared experience for families and can affect all aspects of family functioning.

On the positive side it can broaden horizons, increase family members’ awareness of their inner strength, enhance family cohesion, and encourage connections to community. On the other hand, the time and financial costs, physical and emotional demands, and logistical complexities associated with caring for a disabled child/adult can have far-reaching effects. The impacts will likely depend on the type of condition and severity, as well as the physical, emotional, and financial wherewithal of the family and the resources that are available.

For families, caring for a disabled family member may increase stress, take a toll on mental and physical health, make it difficult to find appropriate and affordable child care, and affect decisions about work, education/training, having additional children, and relying on public support. It may be associated with guilt, blame, or reduced self-esteem. It may divert attention from other aspects of family functioning. The out-of-pocket costs of medical care and other services may be enormous. All of these potential effects could have repercussions for the quality of the relationship between family members, their living arrangements, and future relationships and family structure.

The day-to-day strain of providing care and assistance leads to exhaustion and fatigue, taxing the physical and emotional energy of family members. There are a whole set of issues that create emotional strain, including worry, guilt, anxiety, anger, and uncertainty about the cause of the disability, about the future, about the needs of other family members, about whether one is providing enough assistance, and so on. Grieving over the loss of function of the person with the disability is experienced at the time of onset, and often repeatedly at other stages in the person's life.

Family life is changed, often in major ways. Care-taking responsibilities may lead to changed or abandoned career plans. Female family members are more likely to take on care giving roles and thus give up or change their work roles. This is also influenced by the fact that males are able to earn more money for work in society. When the added financial burden of disability is considered, this is the most efficient way for families to divide role responsibilities.

New alliances and loyalties between family members sometimes emerge, with some members feeling excluded and others being overly drawn in. For example, the primary caregiver may become overly involved with the person with disability. This has been noted particularly with regard to mothers of children with disabilities. In these families, fathers often are under involved with the child and instead immerse themselves in work or leisure activities. This pattern usually is associated with more marital conflict. It is important to note, however, that there does not appear to be a greater incidence of divorce among families who have a child with a disability, although there may exist more marital tension (Hirst 1991; Sabbeth and Leventhal 1984).

The disability can consume a disproportionate share of a family's resources of time, energy, and money, so that other individual and family needs go unmet. Families often talk about living "one day at a time." The family's lifestyle and leisure activities are altered. A family's dreams and plans for the future may be given up. Social roles are disrupted because often there is not enough time, money, or energy to devote to them (Singhi et al. 1990).

Friends, neighbors, and people in the community may react negatively to the disability by avoidance, disparaging remarks or looks, or overt efforts to exclude people with disabilities and their families. Despite the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, many communities still lack programs, facilities, and resources that allow for the full inclusion of persons with disabilities. Families often report that the person with the disability is not a major burden for them. The burden comes from dealing with people in the community whose attitudes and behaviors are judgmental, stigmatizing, and rejecting of the disabled individual and his or her family (Knoll 1992; Turnbull et al. 1993). Family members report that these negative attitudes and behaviors often are characteristic of their friends, relatives, and service providers as well as strangers (Patterson and Leonard 1994).

Overall, stress from these added demands of disability in family life can negatively affect the health and functioning of family members (Patterson 1988; Varni and Wallander 1988). Numerous studies report that there is all increased risk of psychological and behavioral symptoms in the family members of persons with disabilities (Cadman et al. 1987; Singer and Powers 1993; Vance, Fazan, and Satterwhite 1980). However, even though disability increases the risk for these problems, most adults and children who have a member with a disability do not show psychological or behavioral problems. They have found ways to cope with this added stress in their lives. Increasingly, the literature on families and disabilities emphasizes this adaptive capacity of families. It has been called family resilience (Patterson 1991b; Singer and Powers 1993; Turnbull et al. 1993). Many families actually report that the presence of disability has strengthened them as a family—they become closer, more accepting of others, have deeper faith, discover new friends, develop greater respect for life, improve their sense of mastery, and so on.

While there are many commonalities regarding the impact of disabilities on families, other factors lead to variability in the impact of disability on the family. Included in these factors are the type of disability, which member of the family gets the disability, and the age of onset of the disability.

Consider the course of the condition. When it is progressive (such as degenerative arthritis or dementia), the symptomatic person may become increasingly less functional. The family is faced with increasing caretaking demands, uncertainty about the degree of dependency and what living arrangement is best, as well as grieving continuous loss. These families need to readjust continuously to the increasing strain and must be willing to find and utilize outside resources. If a condition has a relapsing course (such as epilepsy or cancer in remission), the ongoing care may be less, but a family needs to be able to reorganize itself quickly and mobilize resources when the condition flares up. They must be able to move from normalcy to crisis alert rapidly. An accumulation of these dramatic transitions can exhaust a family. Disabilities with a constant course (such as a spinal cord injury) require major reorganization of the family at the outset and then perseverance and stamina for a long time. While these families can plan, knowing what is ahead, limited community resources to help them may lead to exhaustion.

Disabilities where mental ability is limited seem to be more difficult for families to cope with (Breslau 1993; Cole and Reiss 1993; Holroyd and Guthrie 1986). This may be due to greater dependency requiring more vigilance by family members, or because it limits the person's ability to take on responsible roles, and perhaps limits the possibilities for independent living. If the mental impairment is severe, it may create an extra kind of strain for families because the person is physically present in the family but mentally absent. This kind of incongruence between physical presence and psychological presence has been called boundary ambiguity (Boss 1993). Boundary ambiguity means that it is not entirely clear to family members whether the person (with the disability in this case) is part of the family or not because the person is there in some ways but not in others. Generally, families experience more distress when situations are ambiguous or unclear because they do not know what to expect and may have a harder time planning the roles of other family members to accommodate this uncertainty.

The age of the person when the disability emerges is associated with different impacts on the family and on the family's life course, as well as on the course of development for the person with disability (Eisenberg, Sutkin, and Jansen 1984). When conditions emerge in late adulthood, in some ways this is normative and more expectable. Psychologically it is usually less disruptive to the family. When disability occurs earlier in a person's life, this is out of phase with what is considered normative, and the impact on the course of development for the person and the family is greater. More adjustments have to be made and for longer periods of time.

When the condition is present from birth, the child's life and identity are shaped around the disability. In some ways it may be easier for a child and his or her family to adjust to never having certain functional abilities than to a sudden loss of abilities later. For example, a child with spina bifida from birth will adapt differently than a child who suddenly becomes a paraplegic in adolescence due to an injury.

The age of the parents when a child's disability is diagnosed is also an important consideration in how the family responds. For example, teenage parents are at greater risk for experiencing poor adaptation because their own developmental needs are still prominent, and they are less likely to have the maturity and resources to cope with the added demands of the child. For older parents there is greater risk of having a child with certain disabilities, such as Down syndrome. Older parents may lack the stamina for the extra burden of care required, and they may fear their own mortality and be concerned about who will care for their child when they die.

As children with disabilities move into school environments where they interact with teachers and peers, they may experience difficulties mastering tasks and developing social skills and competencies. Although schools are mandated to provide special education programs for children in the least restrictive environment and to maximize integration, there is still considerable variability in how effectively schools do this. Barriers include inadequate financing for special education; inadequately trained school personnel; and, very often, attitudinal barriers of other children and staff that compromise full inclusion for students with disabilities. Parents of children with disabilities may experience a whole set of added challenges in assuring their children's educational rights. In some instances, conflict with schools and other service providers can become a major source of strain for families (Walker and Singer 1993). In other cases, school programs are a major resource for families.

When disability has its onset in young adulthood, the person's personal, family, and vocational plans for the future may be altered significantly. If the young adult has a partner where there is a long-term commitment, this relationship may be in jeopardy, particularly if the ability to enact adult roles as a sexual partner, parent, financial provider, or leisure partner is affected (Ireys and Burr 1984).

When the onset of disability occurs to adults in their middle years, it is often associated with major disruption to career and family roles. Those roles are affected for the person with the disability as well as for other family members who have come to depend on him or her to fulfill those roles. Some kind of family reorganization of roles, rules, and routines is usually required. If the person has been employed, he or she may have to give up work and career entirely or perhaps make dramatic changes in amount and type of work.

Children of a middle-aged adult with a disability also experience role shifts. Their own dependency and nurturing needs may be neglected. They may be expected to take on some adult roles, such as caring for younger children, doing household chores, or maybe even providing some income. How well the family's efforts at reorganization work depends ultimately on the family's ability to accommodate age-appropriate developmental needs. In families where there is more flexibility among the adults in assuming the different family roles, adjustment is likely to be better.

The birth of a child with disability usually follows five stages in family :

1) Denial,

2) Anger,

3) Bargaining,

4) Depression

5) Acceptance

Coping Strategies

· Parents deals with stressful situation in the following manner

· By altering expectation

· Amelioration/ To make better of the problem

· By identifying with the problem

Coping Recourses

— Internal Resources

— Faith in god

— Energy

— Self determination

— Problem solving skill

— Socio-economic status

— General & specific beliefs

— External Resource

— Community acceptance

— Strong extended family

— Supportive partner

— Close friends & relatives

— Non-judgmental professional

Inhibitors Of coping

— Poor physical health of family member

— Family problem

— Loss of support

— Lack of acceptance: Family, society, relatives , friends , coworkers

— Over indulgence by others and outsiders

— Misguidance by professionals

— Financial constrain

— Lack of information

— Misconception

— Behaviour problem

2.2 Involving parents in diagnosis, fitment of aids and acceptance of disability by family.

The diagnosis process, itself, is not easily defined. It is influenced by many factors. The child’s actual disability, the age of the child at diagnosis, and the agency or professional making the diagnosis can all influence the process. Therefore, it may be different for each family. For some families the diagnosis process may begin soon after the birth of the child, or even before, and end shortly there after with the disclosure of genetic test results. For other families the process may be much longer and never have a definitive ending point. Some families ultimately arrive at what they believe to be an accurate diagnosis, some keep searching indefinitely, while others forgo the search before ever receiving a definitive diagnosis.

Many researchers and families seem to define the beginning of the process as the time when concerns about the child’s health or development were first expressed. This initial concern may be expressed by professionals or by parents. Those concerns then often lead to an evaluation of some kind, whether medical, educational, therapeutic, or a combination of these disciplines. Different disciplines often have different names for the diagnosis process, as well. Evaluation, assessment, identification, and diagnosis can all mean the same thing for different professionals. These different terms give insight into the various purposes of the diagnosis process. Professionals may use diagnosis for eligibility for educational or therapeutic services, permission for pharmaceutical or surgical interventions, or any combination of these.

The various terms used by professionals also correspond to their chosen professional branch with the term “diagnosis” originating with the medical profession. Historically, disabilities were diagnosed by medical professionals. As will be discussed further in the context section, the medical profession has been joined by many other diagnosing agencies over the last 30 years and for the sake of consistency I have chosen to use the term “diagnosis” for all professional branches.

For some families the disclosure of the evaluation results and subsequent follow up ends the diagnosis process and begins the treatment process. For other families it may be only the first of many evaluations and tests that may or may not eventually lead to a definitive diagnosis. Many families may only receive a diagnosis of a delay in development without a clear reason for the delay. For these families the diagnosis process may only end when they choose to stop searching for a more definitive diagnosis. The diagnosis and treatment processes may overlap. An initial diagnosis of developmental delay may qualify a child for services but parents and/or professionals may continue to search for a more refined diagnosis.

Most children are diagnosed with special needs through parental pursuit of a diagnosis. While some children may be diagnosed through medical testing either shortly after birth or during routine care, the majority of disability diagnoses are made only after parental initiation of the process. Parents may pursue a diagnosis for their child for a number of reasons. Many parents pursue a diagnosis because it often holds the key to services to meet their child’s deficit areas. If parents want help for their children it is very often granted only after it has been proven, or diagnosed, that their child has a special need. Most services are fiscally dependant on a diagnosis. Whether the source is state funding or private insurance, a diagnosis is frequently needed to pay for the subsequent therapy services. The two are inextricably linked. Parents have refused services that they wanted for their child because the services came with a diagnosis or label that they did not want to accept. One must have a diagnosis to get services. The pursuit of services can be a driving force in the pursuit of a diagnosis.

Another reason parents pursue a diagnosis for their child is knowledge. Most parents of children with special needs accurately perceive their child’s deficits and want an explanation for them. Other families have been referred to a diagnosing agency by concerned friends, family, or doctors and want more information that either dismisses or confirms these concerns. While most families wish for a person of authority to tell them that their child is fine and perfect, many families can be relieved to receive a diagnosis of a special need as well. A diagnosis can tell them that they are accurate assessors of their child’s needs and that they are “not crazy” for thinking these things about their child. A diagnosis can give them a course of action, a likely prognosis, and a network of support. All parents want to know how their child will grow and develop, what they can do to help their child progress, and some sort of support in doing so. For parents of children with special needs who often don’t follow typical growth and development patterns, this kind of information and support can be crucial.

Because the diagnosis process is the family’s first knowledge of or confirmation of their child’s special need, it can be an emotionally-laden experience. This is the time in which they begin to redefine themselves as parents of a child with special needs and when they begin to construct how their child’s life will be affected by the disability. How parents cope with this adjustment can be linked to the diagnosis process. It can be easier to adjust to a known diagnosis. Knowledge provided by the diagnosis process can help parents better prepare emotionally for what lies ahead. Parents of children with special needs start out the same as all parents. Like most people they have preconceived notions of what a disabled person or child is like, know little about what to do with that child, and want help making the transition to the parents and caregivers of a child with special needs. Professionals often have much of the information parents seek and how much and how that information is shared can matter tremendously in that family’s life.

Diagnosis is when parents of children with special needs begin to “share” their child with professionals. During this uneasy time professionals play an important role in diagnosing the child with special needs, disclosing the information to parents, and then guiding families through to the next phase of treatment and intervention. This is often the first of many contacts parents have with the professionals that will play an important role in the life of their family. Often based on the interactions during the diagnosis process, parents learn whether they can count on professionals as allies in this new journey or as adversaries.

How parents perceive this process can influence their child’s services. It can influence their interactions with professionals now and in the future. It can influence parents’ acceptance of the disability and their child. It is also likely that it can influence many more aspects not yet discovered.

2.3 Importance of family involvement and advocacy in interventional practices.

Role of families as collaborators

Parents and families of individuals with disability have carried out many roles, some of them unwelcome or unjustified, some born out of necessity, and some of them eagerly embraced.

These roles were the sources of their child's problems, organization members, service organizers, recipients of professionals' decisions, learners and teachers, political advocates, educational decision makers, and collaborators (Turnbull & Turnbull, 1997)

Definition and meaning of family support

Family support has been defined ‘as any and all actions that serve to strengthen and sustain the family system, especially as these actions pertain to the family's assimilation and understanding of the child's disability’ (Dunlap & Fox, 1996).

Family Support

The support a family should be developed in partnership with the family, based on a family systems orientation, and implemented with the goal of strengthening family capacities.

Social and Emotional Support

Many people tend to see disability as a tragedy, and some parents experience continuing disappointment and grief at all stages of the child and family's life cycle.

However, Sinclair (1993) whose child has autism stated that the grief does not stem from the child's disability in itself.

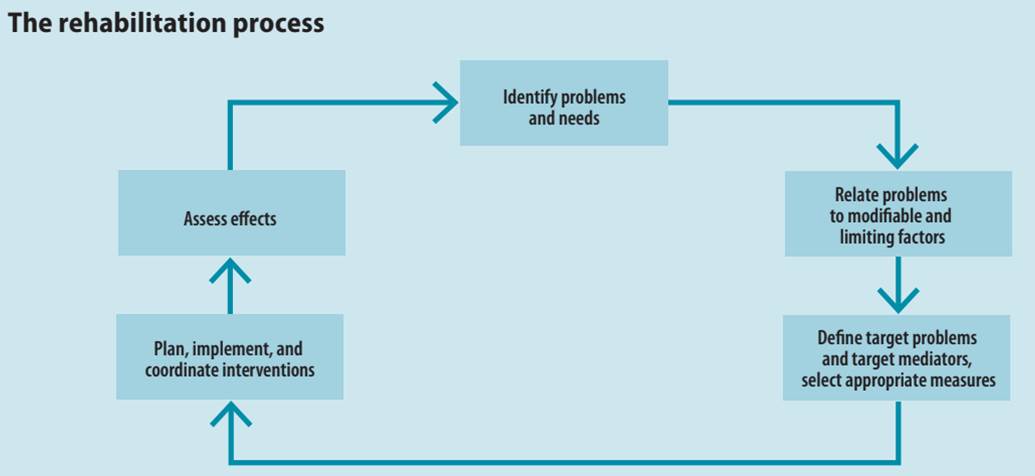

Rehabilitation has long lacked a unifying conceptual framework (1). Historically, the term has described a range of responses to disability, from interventions to improve body function to more comprehensive measures designed to promote inclusion (see Box 4.1). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provides a framework that can be used for all aspects of rehabilitation. For some people with disabilities, rehabilitation is essential to being able to participate in education, the labour market, and civic life. Rehabilitation is always voluntary, and some individuals may require support with decision-making about rehabilitation choices. In all cases rehabilitation should help to empower a person with a disability and his or her family.

Parents are the central and most important link in the care, education, and supervision of persons with intellectual disability (ID). Despite this major role, the literature tends to minimize their significance. Even in Israel, despite the great importance of family, the role of parents is rarely discussed. Professional literature dealing with parents' patterns of coping with raising a handicapped/disabled child describes a wide spectrum of patterns, ranging from reactions of mourning and crisis to those of acceptance. It is very important to examine parents as coping people and the developmentally disabled as children, adolescents, and adults with special needs.

2.4 Concept, components and strategies of family empowerment.

Based on the definition used in a previous study, we defined family empowerment as “the ability of the family of a child with a disability and special needs to control their own lives independently, and the process involved in the same.”

Family Empowerment provides solution-building services that help parents tackle family problems and fortify family strengths in an effort to promote child safety, well-being and permanency. The program targets families who are at risk of children being removed from a home for abuse or neglect. Through the program we work with the families to solve issues and avoid removal, creating safe and stable homes. This is done through Active Parenting curriculum through groups, workshops, counseling, trainings and more.

It is the intent of the program for families to learn new skills that help the home stay a safe and stable place. A successful outcome for the family will result in children remaining with their family and not enduring the trauma of removal.

In Empowering Families, community-based prevention services are provided to strengthen the protective factors, or positive qualities in families. The services develop skills, personal characteristics, knowledge, relationships, and opportunities to help individuals and families deal with challenges and difficulties experienced in school, work, and life.

- Nurturing and Attachment – When parents and children have strong, healthy feelings for one another, children trust their parents will provide what they need to thrive; including love, acceptance, positive guidance, and protection.

- Knowledge of Child Development – Parents who understand how children grow and develop are able to provide an environment where children can reach their potential.

- Parental Resilience – The ability to effectively manage all types of challenges that occur in life is crucial for parents. Parents who are able to manage stress and function well are less likely to direct anger and frustration toward their children.

- Social Connections – Having a sense of connectedness with constructive, supportive persons and with the community provides encouragement and assistance in meeting the daily challenges of raising a family.

- Support for Parents – Parents who are able to identify and access resources to meet their basic needs including food, clothing, and shelter ensure the health and well-being of their children.

Empowering families strengthens families by giving them a voice and a choice. Strengths-based services are centered around the needs of each individual family. Focusing on the positive qualities every family has, the program supports the family as they identify and change habits and behaviors that challenge their ability to function in a healthy manner.

2.5 Partnering for interventional practices.

Effective partnership between professionals and families would depend upon

· Patience, sympathy and openness on the part of the helpers to understand families perspective

· Doing away with the concept of withholding of information concerning a disabled person

· Discretion in discussion with family

· Involvement of parents in planning and decision making

For the parents to be true partners in rehabilitation,it is essential that the professionals accept that:

· The parents have a right to be involved in the planning, as the child is their ultimate responsibility.

· That the home is the large canvas of the child's life as she spends the major part of her life there.

· That parents are aware of the problems of the child but not able to gauge the impact of disability.

· Parents have a major contribution to make in the life of the child.

· Professional efforts would not yield full results without family involvement.

·

Parents have a right to know the various range of services and

options available to the child and the right to choose the most practical

one.

For the family to be successful in the rehabilitation process of the disabled

person, it is essential that:

· There is demystification about disability. The family does not get confused and bogged down by labels and jargons but are told about the impact of the disability and the abilities of the child.

· The family as a whole decides to put itsbest foot forward to learn, to experiment, with ideas and understand, accept and love the family member with a disability.

· The disability is accepted by one and all and it is acknowledged.

· The family is open to ideas from the professionals.

· That the family is made aware of rehabilitation methods and avenues open to the child.

· The family members are present in decision-making process.

· The family members faithfully adhere to their part in the rehabilitation of the child.

The Parent Association is the structure through which parents/guardians in a school can work together for the best possible education for their children.

The Education Act, 1998 sets down the role of the parent association.

The Parent Association works with the principal, staff and the board of management to build effective partnership of home and school.

Educational research on the involvement of parents in schools shows that children achieve higher levels when parents and teachers work together.

The Parent Association can advise the principal and Board of Management on policy issues and incidents that may require a review of school policy, e.g. Bullying, Safety, Homework, Enrolment, Behaviour problems etc.

Parent Associations can suggest and/or organise extra-curricular activities.

The Parent Association is a support for parents in the school.

The Parent Association can invite speakers to address the parents on issues which are topical or relevant.

The Parent Association is not a forum for complaint against either an individual teacher or parent. The Complaints Procedure is the mechanism for this.

Partnership between the Parent Association and the Principal

The Principal has a central role in the school. S/he is responsible for the day to day management of the school and plays a key leadership role. The Principal is also likely to best know the needs of the school; s/he has responsibility for encouraging the involvement of parents of students in the school, in line with the Education Act, 1998.

It is imperative therefore that the Parent Association and Principal develop a good working relationship and develop a good system for communicating with each other.

When a system of communication has been planned it will be important to review it together from time to time to make sure that it is working for both parties.

Partnership between the Parent Association and the Pupils

Children must have a voice in matters which affect them and their views should be given due weight in accordance with their age and maturity, in line with the National Children’s Strategy 2000-2010. The Parent Association should actively encourage a culture and practice of giving information to pupils and involving them in decisions that affect them e.g. school code of behaviour, anti-bullying policy.

At primary level some schools now have councils for their pupils which are an important mechanism for children to discuss and air their views. Primary school children may also have the opportunity to learn new skills from being members of such councils. Parents should support children in the setting up of pupil councils. Pupil councils give opportunities to parents and the rest of the school community to hear the voice of children in the school. For information on pupil councils and student councils contact the Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs. The Parent Association, with the staff and Board of Management, need to plan together to give pupils real opportunities for involvement and need to involve the pupils themselves in this planning process.

The Parent Association should be a structure that actively supports parents to ensure the best interests of their children. Parents value opportunities to meet other parents and share experiences about bringing up children and helping them to learn.

The Parent Association will be stronger and will help networking if it fully represents all parents. Therefore efforts should be made to:

· Produce materials using straightforward and simple language, that is, avoid abbreviations and the use of jargon and make all communication respectful, unambiguous and clear

· Choose times for meetings that will suit the majority of parents

· Ensure where possible that Parent Association meetings are always held in accessible locations

· Specifically reach out to under-represented parents of children in the school, for example parents from the Traveller and migrant communities, and invite them to become involved with the Parent Association committee.