Unit 4: Competencies of the Care Giver

4.1. Knowledge and Insight about the condition and acceptance

4.2. Intervention Development - programme planning for individuals with high support needs.

4.3. Addressing common medical issues and health related resources

4.4. Making reasonable adjustments including, physical comforts and positioning, Communication, environment, meeting personal needs, maintaining privacy, prevention from exploitation, caring for emotional health, meeting leisure and recreation needs

4.5. Exercising fundamental rights of people with disabilities

4.1 Knowledge and Insight about the condition and acceptance

Perception of disability is an important construct affecting not only the well-being of individuals with disabilities, but also the moral compass of the society. Negative attitudes toward disability disempower individuals with disabilities and lead to their social exclusion and isolation. By contrast, a healthy society encourages positive attitudes toward individuals with disabilities and promotes social inclusion. The current review explored disability perception in the light of the in-group vs. out-group dichotomy, since individuals with disabilities may be perceived as a special case of out-group. We implemented a developmental approach to study perception of disability from early age into adolescence while exploring cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of children’s attitudes. Potential factors influencing perception of disability were considered at the level of society, family and school environment, and the individual. Better understanding of factors influencing the development of disability perception would allow the design of effective interventions to improve children’s attitudes toward peers with disabilities, reduce intergroup biases, and promote social inclusion. Based on previous research in social and developmental psychology, education, and anthropology, we proposed an integrative model that provides a conceptual framework for understanding the development of disability perception.

Parental Factors Affecting Perception of Disability

Family plays a significant role in shaping children’s beliefs and attitudes toward others: parenting styles and children’s attachment styles may determine the child’s future attitudes toward individuals with disabilities. Importantly, there is an intricate interplay between parental factors and children’s personality factors.

Parental Influences

Being the primary agents integrating children into society, parents may significantly influence their children’s attitudes toward out-groups in general and individuals with disabilities in particular. However, previous research showed inconsistent findings relating parents’ and children’s beliefs about people with disabilities: some found positive relation, while others found no relation.

Importantly, parents may communicate their beliefs and attitudes to children explicitly – through discussions or explicit teaching, or implicitly – by modeling their values in daily interactions with other people or by providing their children opportunities to interact with out-group peers. While this differentiation is important, it still does not lead to consensus. Thus, some researchers reported that children’s attitudes toward out-groups were related to their parents’ explicit, rather than implicit, expression of out-group attitudes. By contrast, others showed the effectiveness of implicit communication: parents’ implicit stereotyping facilitated children’s intergroup biases, whereas parents’ intergroup friendships reduced children’s intergroup biases. Explicit parent-child discussions of disabilities increase children’s knowledge regarding disabilities which, in turn, reduces the child’s intergroup biases.

Children’s age may play a significant role in the relation between parents’ and children’s attitudes. For example, young children may have fewer opportunities to explicitly discuss intergroup biases with their parents because the latter do not believe their children are ready for such conversations. Moreover, young children may not be socially savvy enough to effectively process the implicit beliefs and attitudes communicated by their parents in daily interactions. Finally, older children may be more susceptible to social desirability concerns that would limit the explicit expression of prejudices and intergroup biases and make their explicitly expressed attitudes toward out-groups more similar to those of their parents who have been functioning under the same social desirability pressures. In accord with these notions, previous research found that children’s attitudes appeared to be more associated with parents’ attitudes as children become older, at least from the age of 5–6-years).

Parenting Styles

Parenting practices to a large extent affect children’s personality traits and attitudes toward others. Parenting can be classified according to responsiveness and control dimensions, resulting in four parental styles: authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and uninvolved. Authoritarian parents are demanding, but not responsive; they promote over-control, obedience to authority, rigidity, and use of punishment. Authoritative parents show high responsiveness and high control; they are warm but demanding, they set rules and provide guidance, but also promote respect and autonomy. Permissive parents are warm and responsive, but not demanding; they do not set rules, but provide ample autonomy. Uninvolved parents are cold and undemanding; their children receive no warmth, no rules, and very little attention or guidance.

Research on permissive and uninvolved parenting styles in relation to children’s views and attitudes produced inconclusive results. By contrast, the authoritarian parenting style has been shown to be associated with conservative views in grown-up children, whereas authoritative parenting is associated with liberal views. In general, under-controlled children tend to grow up to be adults with liberal views, while over-controlled children often become conservatives. Strict, unaffectionate, and punitive parenting produces social conformists who perceive the world as hostile and threatening, promote authoritarian sociopolitical attitudes and are more likely to display intergroup biases.

Parents’ sociopolitical attitudes may be passed to their children via parental practices that shape specific personality traits. For example, parents with conservative views tend to enforce strict rules, discipline, and respect for authority. These parental practices, in turn, are more likely to produce a fearful individual with low self-esteem, who may be protective of the in-group and discriminative toward out-groups. By contrast, parents with liberal views tend to be loving and empathetic; they foster the same loving, emphatic, accepting, and open-minded attitude in their children; these grown-up children are more likely to condemn intergroup biases and social exclusion.

Furthermore, authoritative parenting, use of inductive reasoning, and healthy limit setting are all associated with higher levels of children’s empathy, whereas authoritarian parenting, excessive parental control, power assertion, and harsh punishment are associated with lower levels of children’s empathy. Since empathy promotes the development of social skills, authoritative parenting yields the best outcomes in terms of children’s emotional intelligence, social-behavioral skills, and social competence; the latter, in turn, may increase children’s positive peer relationships and acceptance of peers with disabilities. By contrast, authoritarian parenting, which is related to decreased emotional understanding, may result in more negative attitudes toward peers with disabilities.

Attachment Styles

Parental practices shape the individual’s attachment style, which further frames the individual’s future social attitudes and relationships. Parents serve as a secure base for infants to explore their environment while being protected from possible threats. The level of availability, responsiveness, and supportiveness of a caregiver (the attachment figure) determines the social mental models that individuals use to build their relationships with important others during the lifetime.

The security of the parent-infant attachment is usually tested in the Strange Situation paradigm. When being separated from the mother in the presence of a stranger in an unfamiliar setting, children show different responses in terms of seeking and maintaining contact with a caregiver, avoiding contact, or resisting contact. Infants’ dispositional differences in the Strange Situation are manifested in the following dichotomies: sociability vs. fear, affiliation vs. exploration, and approach vs. avoidance. Behaviors exhibited by infants in the Strange Situation classify them as having a secure, insecure anxious-ambivalent, or insecure avoidant attachment.

Securely attached infants actively explore their surroundings, maintain contact with the mother, approach the stranger, become distressed when separated from the mother and easily comforted upon her return. As adults, these individuals are approach-oriented, dependable, and trustworthy. By contrast, avoidantly attached infants show less exploration and avoid contacting the mother or the stranger; they do not demonstrate strong positive or negative emotions upon the mother’s departure or return. Adults with avoidant/dismissive attachment style have a hard time trusting others and getting into close, intimate relationships. Finally, anxious-ambivalent infants show low levels of exploration, are reluctant to initiate contact with the stranger, become visibly distressed when separated from the mother, and display inconsistent emotions upon her return. As adults, they worry excessively about their relationships with others and tend to get too close to others, often scaring them away. Moreover, individuals scoring high on the anxiety dimension tend to have lower self-esteem and less positive self-views than their more securely attached peers.

The attachment style formed during infancy determines to a large extent the person’s future sense of security, social life, and worldviews. Responsive parenting establishes a secure base for the exploration of environment and tolerance of novelty and uncertainty. In general, secure attachment is typically associated with liberalism, whereas insecure anxious-ambivalent attachment is linked to conservative views in grown-up children.

Secure attachment may enable people to embrace differences in the members of out-groups; even priming secure attachment (secure base schema) reduced negative evaluations of out-group members, irrespective of the individual’s underlying attachment style. By contrast, individuals with insecure attachment in interpersonal relationships tend to seek security in their affiliation with groups or institutions, which triggers intergroup biases and social exclusion of out-group members.

Furthermore, the feeling of vulnerability stemming from an insecure attachment may result in defensive stereotyping and exclusion of out-group members perceived as “strangers” during adulthood. For example, people with higher levels of social anxiety would compare themselves to unfamiliar others using a greater number of attributes/dimensions and a greater number of comparisons per dimension, thus, being less likely to perceive similarity and in-group affiliation, and more likely to protect in-group through defense and support punitive policies against out-group. In summary, parental responsiveness to an infant may determine the quality of the secure base that the individual would use in social relationships with others and shape the individual’s attitudes toward out-group members.

4.2 Intervention Development - programme planning for individuals with high support needs.

The unit of care and support when a person has a disability should be the family or caregiving system, not just the individual (McDaniel, Hepworth, and Doherty 1992). As already noted, the family is both affected by the disability and is a major source of capabilities for responding to it.

At the heart of the family support movement is the concept of family empowerment, which is defined as enabling an individual or family to increase their abilities to meet needs and goals and maintain their autonomy and integrity (Patterson and Geber 1991). Rather than the helper doing everything for the person being helped, thus maintaining dependency, a process is begun whereby the help-seeker discovers and builds on his or her own strengths, leading to a greater sense of mastery and control over his or her life.

Professionals who provide services to persons with

disabilities and their families are being challenged to use this orientation

when working with families. Training programs have curricula for developing

these skills in new professionals. The emphasis is on the process of providing services and not just the outcomes. Empowerment involves believing in and building on the

inherent strengths of families; respecting their values and beliefs; validating

their perceptions and experiences as real; creating opportunities for family

members to acquire knowledge and skills so they feel more competent; mobilizing

the family to find and use sources of informal support in the community; and

developing a service plan together and sharing responsibility for it (Dunst et

al. 1993; Knoll 1992).

Coordination is another important way by which

service delivery can be improved for persons with disabilities. Many persons

need a multiplicity of services, and often they do not know what they are

eligible for or where to find it. Case management or care coordination is

needed to provide this information, to create linkages among these providers,

and to assure that families are given complete and congruent information

(Sloper and Turner 1992). In some instances, families are able to function as

their own case managers, but this requires a high level of knowledge as well as

skill in dealing with a bureaucratic system. Furthermore, it consumes a lot of

time that many family members would prefer to devote to meeting other family

needs. High-quality care coordination can reduce costs, relieve family stress,

and improve the quality of life for persons with disabilities.

Another strategy to facilitate family coping and adaptation is linking persons

with disabilities and their families together in support programs. There are

many support groups for specific conditions (epilepsy, spina bifida, etc.)

across the country that meet regularly to provide information and emotional

support to those living with disability. In other instances, someone who has

lived with the disability for a long time is paired with someone newly

diagnosed (Santelli et al. 1993). These informal connections (in contrast to

professional therapy services) are particularly effective because people feel

they are not alone and are not abnormal in their struggles. There is the

opportunity both to give and to receive support, which benefits both sides.

While family members are the primary source for providing care and assistance to a person with a disability, many families are unable to do this for an extended period of time without help from other community sources (Nosek 1993). Many persons with disability now use personal assistance services on a regular basis, which relieves the family of these tasks and allows them to interact with the person with a disability in more normative ways. In addition, personal assistants contribute to an adult's ability to make independent choices about where he or she will live. It makes it possible to transition from the family home and to live as an adult in the community.

Respite care is another community resource that can give families a break from caretaking and prevent total burnout and exhaustion (Folden and Coffman 1993). Respite care is usually provided on an as-needed basis, in contrast to personal assistants, who are usually available every day. When these kinds of resources are available to support families in their caregiving efforts, the families are better able to keep the persons with disability at home, and they do not have to turn to institutional placement.

Many different types of interventions have been developed by psychologists, social workers, and other mental health professionals for families who have members with disabilities (Singer and Powers 1993). These psychoeducational interventions are designed with a variety of goals in mind. They may be designed to support families in dealing with their emotional responses or to teach skills and strategies for managing difficult behavior. Programs may teach techniques for managing stress more effectively, or they may teach family members how to interact with professional providers of services. Some programs target one individual in the family, such as the primary caregiver; in other instances the whole family is the unit of intervention (Gonzalez, Steinglass, and Reiss 1989). Many families with members with disabilities are reluctant to use psychological resources because they cannot find time to go or they may interpret use as a judgment that they are not competent. Generally, persons from lower socioeconomic groups are more likely to view therapy as stigmatizing and so do not participate. Given the evidence that disability increases stress in families and increases the chance that someone will experience psychological or behavioral problems, programs and services to help families cope could prevent many of these secondary problems.

4.3 Addressing common medical issues and health related resources

Disability is often not perceived as a health issue. Therefore, action is not taken towards disability inclusion in the health sector, which is also often overlooked in national disability strategies and action plans to implement and monitor the CRPD.

Attaining the highest possible standard of health and well-being for all will only be possible if governments understand the need for a paradigm shift, recognizing that the global health goals can only be achieved when disability inclusion is intrinsic to health sector priorities, including:

- universal health coverage without financial hardship

- protection during health emergencies

- access to cross-sectorial public health interventions, such as water, sanitation and hygiene services.

Disability inclusion is critical to achieving universal health coverage without financial hardship, because persons with disabilities are:

- three times more likely to be denied health care

- four times more likely to be treated badly in the health care system

- 50% more likely to suffer catastrophic health expenditure.

Disability inclusion is critical to achieving better protection from health emergencies, because persons with disabilities are disproportionately affected by COVID-19, including:

- directly due to increased risk of infection and barriers in accessing healthcare

- indirectly due to restrictions to reduce spread of virus (e.g., disruptions in support services).

Disability inclusion is critical to achieving better health and well-being, because persons with disabilities are:

- 4–10 times more likely to experience violence

- at higher risk of nonfatal injury from road traffic crashes.

Children with disabilities are:

- three times more likely to experience sexual abuse

- two times more likely to be malnourished.

To improve access to and coverage of health services for people with disability, WHO:

- guides and supports Member States to increase awareness of disability issues, and promotes the inclusion of disability as a component in national and sub-national health programmes;

- facilitates collection and dissemination of disability-related data and information;

- develops normative tools, including guidelines to strengthen disability inclusion within health care services;

- builds capacity among health policymakers and service providers;

- promotes strategies to ensure that people with disability are knowledgeable about their own health conditions, and that health care personnel support and protect the rights and dignity of persons with disability;

- contributes to the United Nations Disability Inclusion Strategy (UNDIS) to promote “sustainable and transformative progress on disability inclusion through all pillars of work of the United Nations”; and

- provides Member States and development partners with updated evidence, analysis and recommendations related to disability inclusion in the health sector.

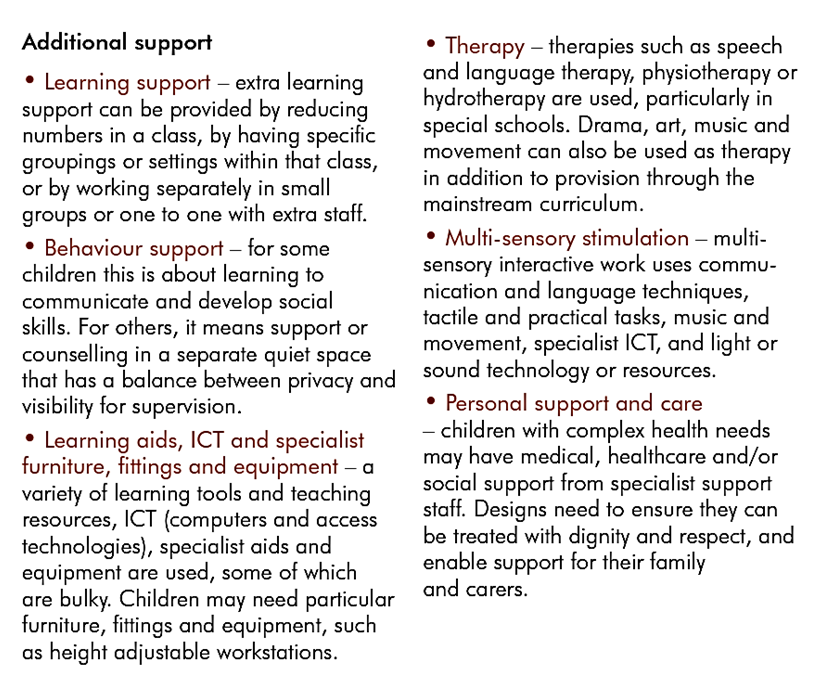

4.4 Making reasonable adjustments including, physical comforts and positioning, Communication, environment, meeting personal needs, maintaining privacy, prevention from exploitation, caring for emotional health, meeting leisure and recreation needs

Behaviour, emotional and social development

Children who have behavioural, emotional and social difficulties may be withdrawn or isolated, disruptive and disturbing and they may be hyperactive. They may lack concentration and have immature social skills. Challenging behaviour may arise from other complex special needs. Children who have these needs may require a structured learning environment, with clear boundaries for each activity. They may need extra space to move around and to ensure a comfortable distance between themselves and others. They may take extreme risks or have outbursts and need a safe place to calm down. Behaviour support or counselling may take place in a quiet supportive environment.

Communication and interaction

Most children with special educational needs have strengths and difficulties in one, some or all of the areas of speech, language and communication. The range of difficulties will encompass children with a speech and language impairment or delay, children with learning difficulties, those with a hearing impairment and those who demonstrate features within the autistic spectrum. Children with these needs require support in acquiring, comprehending and using language, and may need specialist support, speech and language therapy or language programmes, augmentative and alternative means of communication and a quiet place for specialist work. Children with autistic spectrum disorder have difficulty interpreting their surroundings and communicating and interacting with others. They need an easily understood environment with a low level of distraction and sensory stimulus to reduce anxiety or distress. They may need a safe place to calm down.

Sensory and/or physical needs

There is a wide spectrum of sensory, multi-sensory and physical difficulties. Sensory needs range from profound and permanent deafness or visual impairment through to lesser levels of loss, which may only be temporary. For some children these needs may be accompanied by more complex learning and social needs.

Children with these needs require access to all areas of the curriculum and may use specialist aids, equipment or furniture. Many will need specialist support (for example mobility training or physiotherapy). Children with sensory impairments may need particular acoustic or lighting conditions. Some may need extra space and additional ‘clues’ to help them negotiate their environment independently.

Children with physical disabilities may use mobility aids, wheelchairs, or standing frames, which can be bulky and require storage. Whether they are able to move around independently or need support, there should be sufficient space for them to travel alongside their friends. Accessible personal care facilities should be conveniently sited.

Health and personal care needs

Pupils with a range of medical needs may count as disabled under the DDA and may or may not have accompanying special educational needs. They may need facilities where their medical or personal care needs can be met in privacy.

ACCESS FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Physical access

This means access to buildings, public spaces, and any other place a person might need to go for work, play, education, business, services, etc. Physical access includes things like accessible routes, curb ramps, parking and passenger loading zones, elevators, signage, entrances, and restroom accommodations.

Access to communication and information

Signs, public address systems, the Internet, telephones, and many other communication media are oriented toward people who can hear, see and use their hands easily. Making these media accessible to people with disabilities can take some creativity and ingenuity.

Program accessibility

People with disabilities have, in the past, often been denied access to services of various kinds – from child care or mental health counseling to help in retail stores to entertainment – either due to lack of physical accessibility or because of discomfort, unfamiliarity, or prejudices regarding their disabilities.

Employment

Discrimination in hiring on the basis of disability – as long as the disability doesn’t interfere with a candidate’s ability to perform the tasks of the job in question – is illegal in the U.S. and many other countries, and unfair everywhere.

Education

Everyone has a right to an education appropriate to her talents and needs. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in the U.S., as well as laws in many other countries, guarantee education to students with disabilities. In the case of IDEA, that guarantee extends through high school, while ADA covers undergraduate and graduate students (without discrimination) at colleges and universities.

Community access

Everyone should have the right to fully participate in community life, including attending religious services, dining in public restaurants, shopping, enjoying community park facilities, and the like. Even where there are no physical barriers, people with disabilities still sometimes experience differential treatment.

4.5 Exercising fundamental rights of people with disabilities

The disabled and the constitution

The Constitution of India applies uniformly to every legal citizen of India, whether they are healthy or disabled in any way (physically or mentally)

Under the Constitution the disabled have been guaranteed the following fundamental rights:

1. The Constitution secures to the citizens including the disabled, a right of justice, liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship, equality of status and of opportunity and for the promotion of fraternity.

2. Article 15(1) enjoins on the Government not to discriminate against any citizen of India (including disabled) on the ground of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth.

3. Article 15 (2) States that no citizen (including the disabled) shall be subjected to any disability, liability, restriction or condition on any of the above grounds in the matter of their access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and places of public entertainment or in the use of wells, tanks, bathing ghats, roads and places of public resort maintained wholly or partly out of government funds or dedicated to the use of the general public. Women and children and those belonging to any socially and educationally backward classes or the Scheduled Castes & Tribes can be given the benefit of special laws or special provisions made by the State.

4. There shall be equality of opportunity for all citizens (including the disabled) in matters relating to employment or appointment to any office under the State.

5. No person including the disabled irrespective of his belonging can be treated as an untouchable. It would be an offence punishable in accordance with law as provided by Article 17 of the Constitution.

6. Every person including the disabled has his life and liberty guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution.

7. There can be no traffic in human beings (including the disabled), and beggar and other forms of forced labour is prohibited and the same is made punishable in accordance with law (Article 23).

8. Article 24 prohibits employment of children (including the disabled) below the age of 14 years to work in any factory or mine or to be engaged in any other hazardous employment. Even a private contractor acting for the Government cannot engage children below 14 years of age in such employment.

9. Article 25 guarantees to every citizen (including the disabled) the right to freedom of religion. Every disabled person (like the non-disabled) has the freedom of conscience to practice and propagate his religion subject to proper order, morality and health.

10.No disabled person can be compelled to pay any taxes for the promotion and maintenance of any particular religion or religious group.

11.No Disabled person will be deprived of the right to the language, script or culture which he has or to which he belongs.

12.Every disabled person can move the Supreme Court of India to enforce his fundamental rights and the rights to move the Supreme Court is itself guaranteed by Article 32.

13.No disabled person owning property (like the non-disabled) can be deprived of his property except by authority of law though right to property is not a fundamental right. Any unauthorized deprivation of property can be challenged by suit and for relief by way of damages.

14.Every disabled person (like the non-disabled) on attainment of 18 years of age becomes eligible for inclusion of his name in the general electoral roll for the territorial constituency to which he belongs.

- The right to education is available to all citizens including the disabled. Article 29(2) of the Constitution provides that no citizen shall be denied admission into any educational institution maintained by the State or receiving aid out of State funds on the ground of religion, race, caste or language.

- Article 45 of the Constitution directs the State to provide free and compulsory education for all children (including the disabled) until they attain the age of 14 years. No child can be denied admission into any education institution maintained by the State or receiving aid out of State funds on the ground of religion, race, casteor language.

- Article 47 of the constitution imposes on the Government a primary duty to raise the level of nutrition and standard of living of its people and make improvements in public health - particularly to bring about prohibition of the consumption of intoxicating drinks and drugs which are injurious toone’s health except for medicinal purposes.

- The health laws of India have many provisions for the disabled. Some of the Acts which make provision for health of the citizens including the disabled may be seen in the Mental Health Act, 1987 (See later in the chapter).

Various laws relating to the marriage enacted by the Government for DIFFERENT communities apply equally to the disabled. In most of these Acts it has been provided that the following circumstances will disable a person from undertaking a marriage. These are:

- Where either party is an idiot or lunatic,

- Where one party is unable to give a valid consent due to unsoundness of mind or is suffering from a mental disorder of such a kind and extent as to be unfit for ‘marriage for procreation of children’

- Where the parties are within the degree of prohibited relationship or are sapindas of each other unless permitted by custom or usage.

- Where either party has a living spouse

The rights and duties of the parties to a marriage whether in respect of disabled or non-disabled persons are governed by the specific provisions contained in different marriage Acts, such as the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, the Christian Marriage Act, 1872 and the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1935. Other marriage Acts which exist include; the Special Marriage Act, 1954 (for spouses of differing religions) and the Foreign Marriage Act, 1959 (for marriage outside India). The Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929 as amended in 1978 to prevent the solemnization of child marriages also applies to the disabled. A Disabled person cannot act as a guardian of a minor under the Guardian and

Wards Act, 1890 if the disability is of such a degree that one cannot act as a guardian of the minor. A similar position is taken by the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956, as also under the Muslim Law

Succession Laws for the Disabled

Under the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 which applies to Hindus it has been specifically provided that physical disability or physical deformity would not disentitle a person from inheriting ancestral property. Similarly, in the Indian Succession Act, 1925 which applies in the case of intestate and testamentary succession, there is no provision which deprives the disabled from inheriting an ancestral property. The position with regard to Parsis and the Muslims is the same. In fact a disabled person can also dispose his property by writing a ‘will’ provided he understands the import and consequence of writing a will at the time when a will is written. For example, a person of unsound mind can make a Will during periods of sanity. Even blind persons or those who are deaf and dumb can make their Wills if they understand the import and consequence of doing it.

Labour Laws for the Disabled

The rights of the disabled have not been spelt out so well in the labour legislations but provisions which cater to the disabled in their relationship with the employer are contained in delegated legislations such as rules, regulations and standing orders.

Judicial procedures for the disabled

Under the Designs Act, 1911 which deals with the law relating to the protection of designs any person having jurisdiction in respect of the property of a disabled person (who is incapable of making any statement or doing anything required to be done under this Act) may be appointed by the Court under Section 74, to make such statement or do such thing in the name and on behalf of the person subject to the disability. The disability may be lunacy or other disability.

Relief for Handicapped

- Section 80 DD: Section 80 DD provides for a deduction in respect of the expenditure incurred by an individual or Hindu Undivided Family resident in India on the medical treatment (including nursing) training and rehabilitation etc. of handicapped dependants. For officiating the increased cost of such maintenance, the limit of the deduction has been raised from Rs.12000/- to Rs.20000/-.

- Section 80 V: A new section 80V has been introduced to ensure that the parent in whose hands income of a permanently disabled minor has been clubbed under Section 64, is allowed to claim a deduction upto Rs.20000/- in terms of Section 80 V.

- Section 88B: This section provides for an additional rebate from the net tax payable by a resident individual who has attained the age of 65 years. It has been amended to increase the rebate from 10% to 20% in the cases where the gross total income does not exceed Rs.75000/- (as against a limit of Rs.50000/- specified earlier).

The persons with disabilities (PWD) (equal opportunities, protection of rights and full participation) act, 1995

“The Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995” had come into enforcement on February 7, 1996. It is a significant step which ensures equal opportunities for the people with disabilities and their full participation in the nation building. The Act provides for both the preventive and promotional aspects of rehabilitation like education, employment and vocational training, reservation, research and manpower development, creation of barrier- free environment, rehabilitation of persons with disability, unemployment allowance for the disabled, special insurance scheme for the disabled employees and establishment of homes for persons with severe disability etc.

Main Provisions of the Act

- Prevention and Early Detection of Disabilities

- Education

- Employment

- Non-Discrimination

- Research and Manpower Development

- Affirmative Action

- Social Security

- Grievance Redressal

Prevention and early detection of disabilities

- Surveys, investigations and research shall be conducted to ascertain the cause of occurrence of disabilities.

- Various measures shall be taken to prevent disabilities. Staff at the Primary Health Centre shall be trained to assist in this work.

- All the Children shall be screened once in a year for identifying ‘at-risk’ cases.

- Awareness campaigns shall be launched and sponsored to disseminate information.

- Measures shall be taken for pre-natal, peri natal, and post-natal care of the mother and child.

Education

- Every Child with disability shall have the rights to free education till the age of 18 years in integrated schools or special schools.

- Appropriate transportation, removal of architectural barriers and restructuring of modifications in the examination system shall be ensured for the benefit of children with disabilities.

- Children with disabilities shall have the right to free books, scholarships, uniform and other learning material.

- Special Schools for children with disabilities shall be equipped with vocational training facilities.

- Non-formal education shall be promoted for children with disabilities.

- Teachers’ Training Institutions shall be established to develop requisite manpower.

- Parents may move to an appropriate forum for the redressal of grievances regarding the placement of their children with disabilities.

Employment

3% of vacancies in government employment shall be reserved for people with disabilities, 1% each for the persons suffering from:

- Blindness or Low Vision

- Hearing Impairment

- Locomotor Disabilities & Cerebral Palsy

- Suitable Scheme shall be formulated for

- The training and welfare of persons with disabilities

- The relaxation of upper age limit

- Regulating the employment

- Health and Safety measures and creation of a non- handicapping, environment in places where persons with disabilities are employed

Government Educational Institutes and other Educational Institutes receiving grant from Government shall reserve at least 3% seats for people with disabilities.

No employee can be sacked or demoted if they become disabled during service, although they can be moved to another post with the same pay and condition. No promotion can be denied because of impairment.

Affirmative Action

Aids and Appliances shall be made available to the people with disabilities.

Allotment of land shall be made at concessional rates to the people with disabilities for:

- House

- Business

- Special Recreational Centres

- Special Schools

- Research Schools

- Factories by Entrepreneurs with Disability,

Non-Discrimination

- Public building, rail compartments, buses, ships and air-crafts will be designed to give easy access to the disabled people.

- In all public places and in waiting rooms, the toilets shall be wheel chair accessible. Braille and sound symbols are also to be provided in all elevators (lifts).

- All the places of public utility shall be made barrier- free by providing the ramps.

Research and Manpower Development

- Research in the following areas shall be sponsored and promoted

- Prevention of Disability

- Rehabilitation including community based rehabilitation

- Development of Assistive Devices.

- Job Identification

- On site Modifications of Offices and Factories

- Financial assistance shall be made available to the universities, other institutions of higher learning, professional bodies and non-government research- units or institutions, for undertaking research for special education, rehabilitation and manpower development.

Social Security

- Financial assistance to non-government organizations for the rehabilitation of persons with disabilities.

- Insurance coverage for the benefit of the government employees with disabilities.

- Unemployment allowance to the people with disabilities who are registered with the special employment exchange for more than a year and could not find any gainful occupation

Grievance Redressal

- In case of violation of the rights as prescribed in this act, people with disabilities may move an application to the

- Chief Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities in the Centre, or

- Commissioner for Persons with Disabilities in the State.

Under the Mental Health Act, 1987 mentally ill persons are entitled to the following rights:

1. A right to be admitted, treated and cared in a psychiatric hospital or psychiatric nursing home or convalescent home established or maintained by the Government or any other person for the treatment and care of mentally ill persons (other than the general hospitals or nursing homes of the Government).

2. Even mentally ill prisoners and minors have a right of treatment in psychiatric hospitals or psychiatric nursing homes of the Government.

3. Minors under the age of 16 years, persons addicted to alcohol or other drugs which lead to behavioral changes, and those convicted of any offence are entitled to admission, treatment and care in separate psychiatric hospitals or nursing homes established or maintained by the Government.

4. Mentally ill persons have the right to get regulated, directed and co-ordinated mental health services from the Government. The Central Authority and the State Authorities set up under the Act have the responsibility of such regulation and issue of licenses for establishing and maintaining psychiatric hospitals and nursing homes.

5. Treatment at Government hospitals and nursing homes mentioned above can be obtained either as in patient or on an out-patients basis.

6. Mentally ill persons can seek voluntary admission in such hospitals or nursing homes and minors can seek admission through their guardians. Admission can be sought for by the relatives of the mentally ill person on behalf of the latter. Applications can also be made to the local magistrate for grants of such (reception) orders.

7. The police have an obligation to take into protective custody a wandering or neglected mentally ill person, and inform his relative, and also have to produce such a person before the local magistrate for issue of reception orders.

8. Mentally ill persons have the right to be discharged when cured and entitled to ‘leave’ the mental health facility in accordance with the provisions in the Act.

9. Where mentally ill persons own properties including land which they cannot themselves manage, the district court upon application has to protect and secure the management of such properties by entrusting the same to a ‘Court of Wards’, by appointing guardians of such mentally ill persons or appointment of managers of such property.

10.The costs of maintenance of mentally ill persons detained as in-patient in any government psychiatric hospital or nursing home shall be borne by the state government concerned unless such costs have been agreed to be borne by the relative or other person on behalf of the mentally ill person and no provision for such maintenance has been made by order of the District Court. Such costs can also be borne out of the estate of the mentally ill person.

11.Mentally ill persons undergoing treatment shall not be subjected to any indignity (whether physical or mental) or cruelty. Mentally ill persons cannot be used without their own valid consent for purposes of research, though they could receive their diagnosis and treatment.

12.Mentally ill persons who are entitled to any pay, pension, gratuity or any other form of allowance from the government (such as government servants who become mentally ill during their tenure) cannot be denied of such payments. The person who is in-charge of such mentally person or his dependents will receive such payments after the magistrate has certified the same.

13.A mentally ill person shall be entitled to the services of a legal practitioner by order of the magistrate or district court if he has no means to engage a legal practitioner or his circumstances so warrant in respect of proceedings under the Act.

This Act provides guarantees so as to ensure the good quality of services rendered by various rehabilitation personnel. Following is the list of such guarantees:

1. To have the right to be served by trained and qualified rehabilitation professionals whose names are borne on the Register maintained by the Council

2. To have the guarantee of maintenance of minimum standards of education required for recognition of rehabilitation qualification by universities or institutions in India.

3. To have the guarantee of maintenance of standards of professional conduct and ethics by rehabilitation professionals in order to protect against the penalty of disciplinary action and removal from the Register of the Council

4. To have the guarantee of regulation of the profession of rehabilitation professionals by a statutory council under the control of the central government and within the bounds prescribed by the statute

The national trust for welfare of persons with autism, cerebral palsy, mental retardation and multiple disabilities act, 1999

1. The Central Government has the obligation to set up, in accordance with this Act and for the purpose of the benefit of the disabled, the National Trust for Welfare of Persons with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Mental Retardation and Multiple Disability at New Delhi.

2. The National Trust created by the Central Government has to ensure that the objects for which it has been set up as enshrined in Section 10 of this Act have to be fulfilled.

3. It is an obligation on part of the Board of Trustees of the National Trust so as to make arrangements for an adequate standard of living of any beneficiary named in any request received by it, and to provide financial assistance to the registered organizations for carrying out any approved programme for the benefit of disabled.

4. Disabled persons have the right to be placed under guardianship appointed by the ‘Local Level Committees’ in accordance with the provisions of the Act. The guardians so appointed will have the obligation to be responsible for the disabled person and their property and required to be accountable for the same.

5. A disabled person has the right to have his guardian removed under certain conditions. These include an abuse or neglect of the disabled, or neglect or misappropriation of the property under care.

6. Whenever the Board of Trustees are unable to perform or have persistently made default in their performance of duties, a registered organization for the disabled can complain to the central government to have the Board of Trustees superseded and/or reconstituted.

7. The National Trust shall be bound by the provisions of this Act regarding its accountability, monitoring finance, accounts and audit.

This declaration on the rights of mentally retarded person’s calls for national and international actions so as to ensure that it will be used as a common basis and frame of reference for the protection of their rights:

1. The mentally retarded person has, to the maximum degree of feasibility, the same rights as under human beings.

2. The mentally retarded person has a right to proper medical care, physical therapy and to such education, training, rehabilitation and guidance which will enable him to further develop his ability, and reach maximum potential in life.

3. The mentally retarded person has a right of economic security and of a decent standard of living. He/she has a right to perform productive work or to participate in any other meaningful occupation to the fullest possible extent of capabilities.

4. Whenever possible, the mentally retarded person should live with his own family or with his foster parents and participate in different forms of community life. The family with which he lives should receive assistance. If an institutional care becomes necessary then it should be provided in surroundings and circumstances as much closer as possible to that of a normal lifestyle.

5. The mentally retarded person has a right to a qualified guardian when this is required in order to protect his personal well-being or interests.

6. The mentally retarded person has a right to get protection from exploitation, abuse and a degrading treatment. If prosecuted for any offence; he shall have right to the due process of law, with full recognition being given to his degree of mental responsibility.

7. Whenever mentally retarded persons are unable (because of the severity of their handicap) to exercise their rights in a meaningful way or it should become necessary to restrict or deny some or all of their rights then the procedure(s) used for that restriction or denial of rights must contain proper legal safeguards against every form of abuse. This procedure for the mentally retarded must be based on an evaluation of their social capability by qualified experts, and must be subject to periodic review and a right of appeal to the higher authorities.