Unit 4: Learning characteristics of students with ID

4.1 Basic understanding of intellectual disability, - definition, meaning and description, (concept, aetiology, prevalence, incidence, historical perspective cultural perspective, myths, recent trends and updates)

4.2 Classification of students with ID, learning environment and learning

4.3 Understanding strengths and needs of learners with Intellectual Disabilities

4.4 Learning characteristics, Cognitive process, Sequential processing of information in children with ID

4.5 Level of intellectual disability and its relevance to learning characteristics.

4.1 Basic understanding of intellectual disability, - definition, meaning and description, (concept, aetiology, prevalence, incidence, historical perspective cultural perspective, myths, recent trends and updates)

Pre-Colonial India

Historically, over different periods of time and almost till the advent of the colonial rule in India, including the reigns of Muslim kings, the rulers exemplified as protectors, establishing charity homes to feed, clothe and care for the destitute persons with disabilities. The community with its governance through local elected bodies, the Panchayati system of those times, collected sufficient data on persons with disabilities for provision of services, though based on the philosophy of charity. With the establishment of the colonial rule in India, changes became noticeable on the type of care and management received by the persons with the influence from the West.

Pre-Independence–Changing Life Styles in India

Changes in attitudes towards persons with disabilities also came to about with city life. The administrative authorities began showing interest in providing a formal education system for persons with disabilities, particularly for families which had taken up residences in the cities.

Changes in the lifestyle of the persons with mental retardation were also noticed with their shifting from ‘community inclusive settings’ in which families rendered services to that of services provided in ‘asylums’, run by governmental or non-governmental agencies (Chennai, then Madras, Lunatic Asylum, 1841).

It was at the Madras Lunatic Asylum, renamed the Institute of Mental Health, that persons with mental illness and those with mental retardation were segregated and given appropriate treatment.

Special schools were started for those who could not meet the demands of the mainstream schools (Kurseong, 1918; Travancore, 1931; Chennai, 1938). The first residential home for persons with mental retardation was established in Mumbai, then Bombay (Children Aid Society, Mankhurd, 1941) followed by the establishment of a special school in 1944. Subsequently, 11 more centres were established in other parts of India.

![]()

![]() Post-Independent

India–Current Scenario

Post-Independent

India–Current Scenario

Establishment of Special Schools

Article 41of the Constitution of India (1950) embodied in its clause the “Right to Free and Compulsory Education for All Children up to Age 14 years”.

Many more schools for persons with mental retardation were established including an integrated school in Mumbai (Sushila Ben, 1955).

Notwithstanding this obligatory clause on children’s mainstream education, more and more special schools were also being set up by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in an attempt to meet the parents’ demands.

PWD Act, 1995- Mental retardation means a condition of arrested or incomplete development of mind of a person which is specially characterized by sub normality of intelligence.

RPwD Act 2016- Intellectual disability is a condition of arrested or incomplete development of mind of a person, especially characterized by sub-normality of intelligence.

DSM-5 defines intellectual disabilities as neurodevelopmental disorders that begin in childhood and are characterized by intellectual difficulties as well as difficulties in conceptual, social, and practical areas of living. The DSM-5 diagnosis of ID requires the satisfaction of three criteria:

· Deficits in intellectual functioning—“reasoning, problem solving, planning, abstract thinking, judgment, academic learning, and learning from experience”—confirmed by clinical evaluation and individualized standard IQ testing;

· Deficits in adaptive functioning that significantly hamper conforming to developmental and socio-cultural standards for the individual's independence and ability to meet their social responsibility; and

· The onset of these deficits during childhood.

Definition of Intellectual Disability

Intellectual disability is a disability characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and in adaptive behavior, which covers many everyday social and practical skills. This disability originates before the age of 22.

Intellectual Functioning

Intellectual functioning—also called intelligence—refers to general mental capacity, such as learning, reasoning, problem solving, and so on.

One way to measure intellectual functioning is an IQ test. Generally, an IQ test score of around 70 or as high as 75 indicates a limitation in intellectual functioning.

Adaptive Behavior

Adaptive behavior is the collection of conceptual, social, and practical skills that are learned and performed by people in their everyday lives.

- Conceptual skills—language and literacy; money, time, and number concepts; and self-direction.

- Social skills—interpersonal skills, social responsibility, self-esteem, gullibility, naïveté (i.e., wariness), social problem solving, and the ability to follow rules/obey laws and to avoid being victimized.

- Practical skills—activities of daily living (personal care), occupational skills, healthcare, travel/transportation, schedules/routines, safety, use of money, use of the telephone.

Standardized tests can also determine limitations in adaptive behavior.

The National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) estimates that currently 1.8% of the total Indian population is disabled, yet the data may not be completely accurate. The prevalence of intellectual disability has been estimated at 1-4% i.e. about 20 people per 1000 in the population.

Types of intellectual disabilities

Fragile X syndrome

Fragile X syndrome is the most common known cause of an inherited intellectual disability worldwide. It is a genetic condition caused by a mutation (a change in the DNA structure) in the X chromosome.

People born with Fragile X syndrome may experience a wide range of physical, developmental, behavioural, and emotional difficulties, however, the severity can be very varied.

Some common signs include a developmental delay, intellectual disability, communication difficulties, anxiety, ADHD, and behaviours similar to autism such as hand flapping, difficulty with social interactions, difficulty processing sensory information, and poor eye contact.

Boys are usually more affected than girls – it affects around 1 in 3,600 boys and between 1 in 4,000 – 6,000 girls.

Down syndrome

Down syndrome is not a disease or illness, it is a genetic disorder which occurs when someone is born with a full, or partial, extra copy of chromosome 21 in their DNA.

Down syndrome is the most common genetic chromosomal disorder and cause of learning disabilities in children. In Australia, approximately 270 children, or one in 1,100, are born with Down syndrome each year.

People with Down syndrome can have a range of common physical and developmental characteristics as well as a higher than normal incidence of respiratory and heart conditions.

Physical characteristics associated with Down syndrome can include a slight upward slant of the eyes, a rounded face, and a short stature. People may also have some level of intellectual and learning disabilities, but this can be quite different from person to to another.

Developmental delay

When a child develops at a slower rate compared to other children of the same age, they may have a developmental delay.

One or more areas of development may be affected including their ability to move, communicate, learn, understand, or interact with other children.

Sometimes children with a developmental delay may not talk, move or behave in a way that’s appropriate for their age but can progress more quickly as they grow. For others, their developmental delay may become more significant over time and can affect their learning and education.

Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS)

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare genetic disorder which affects around 1 in 10,000 – 20,000 people. This disability is quite complex and it’s caused by an abnormality in the genes of chromosome 15.

One of the most common symptoms of PWS is a constant and insatiable hunger which typically begins at two years of age. People with PWS have an urge to eat because their brain (specifically their hypothalamus) won’t tell them that they are full, so they are forever feeling hungry.

The symptoms of PWS can be quite varied, but poor muscle tone and a short stature are common. A level of intellectual disability is also common, and children can find language, problem solving, and maths difficult.

Someone with PWS may also be born with distinct facial features including almond-shaped eyes, a narrowing of the head, a thin upper-lip, light skin and hair, and a turned-down mouth.

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD)

FASD refers to a number of conditions that are caused when an unborn foetus is exposed to alcohol.

When a mother is pregnant, alcohol crosses the placenta from the mother’s bloodstream into the baby’s, exposing the baby to similar concentrations as the mother.

The symptoms can vary however can include distinctive facial features, deformities of joints, damage to organs such as the heart and kidneys, slow physical growth, learning difficulties, poor memory and judgement, behavioural problems, and poor social skills.

Many cases are also often misdiagnosed as autism or ADHD as they can have similarities.

The World Health Organisation recommends that mothers-to-be, or those planning on conceiving, should completely abstain from alcohol.

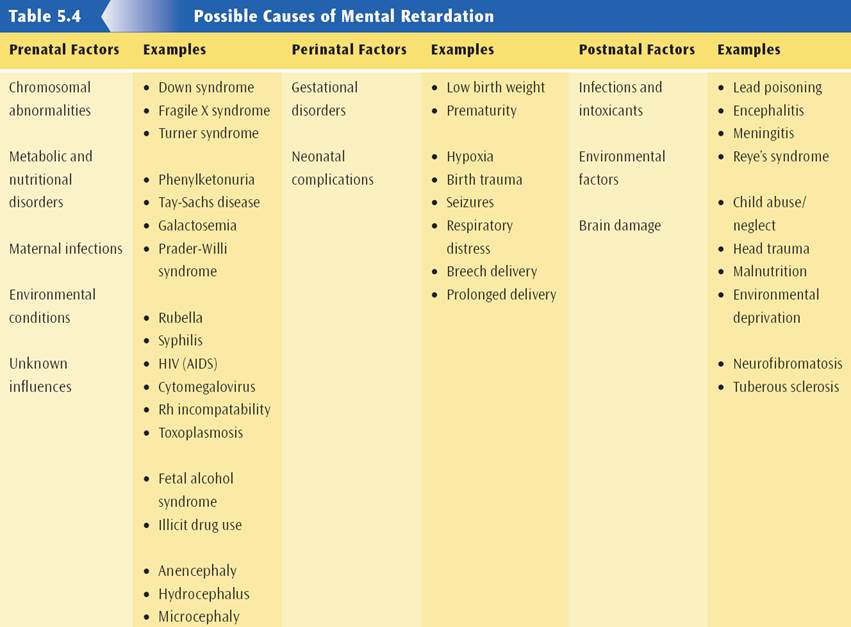

Possible Sources for Causes of Intellectual Disability:

Prenatal (before birth)

– chromosomal, maternal infections, environmental factors, unknown influences

Perinatal (during birth)

– gestational disorders, neonatal complications

Postnatal (after birth)

– infections and intoxicants, environmental factors

Predisposing Factors

§ No clear etiology can be found in about 75% of those with Mild MR and 30 – 40% of those with severe impairment

§ Specific etiologies are most often found in those with Severe and Profound MR

§ No familial pattern (although certain illnesses resulting in MR may be heritable)

Heredity (5% of cases)

– Autosomal recessive inborn errors of metabolism (e.g., Tay-Sachs, PKU)

– Single-gene abnormalities with Mendelian inheritance and variable expression (e.g., tuberous sclerosis)

– Chromosomal aberrations (e.g., Fragile X)

§ Early Alterations of Embryonic Development (30% of cases)

– Chromosomal changes (e.g., Downs)

– Prenatal damage due to toxins (e.g., maternal EtOH consumption, infections)

§ Environmental Influences (15-20% of cases)

– Deprivation of nurturance, social/linguistic and other stimulation

§ Mental Disorders

– Autism & other PDDs

§ Pregnancy & Perinatal Problems (10% of cases)

– Fetal malnutrition, prematurity, hypoxia, viral and other infections, trauma

§ General Medical Conditions Acquired in Infancy or Childhood (5% of cases)

– Infections, trauma, poisoning (e.g., lead)

The following table summaries the causes of Intellectual Disability:

Etiology

– At least 500 causes now known

– Over 150 MR syndromes have been related to the X-chromosome

– Most common cause of MR:

1. Down’s Syndrome (most common genetic cause)

2. Fragile X Syndrome (accounts for 40% of all X-linked syndromes; most common inherited cause)

3. Fetal EtOH Syndrome (most common attributable cause)

4. together these 3 account for 30% of all identified cases of MR

Prevention

Prevention refers to the measures taken to prevent the disability from occurring.

The World Health Organisation (WHO), American Association for Mental Retardation (AAMR), American Association on Mental Deficiency (AAMD), International Classificatioon on Deficiency (ICD), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) definitions of mental retardation relate to three levels of prevention:

· Primary level of prevention is carried out by doctors and health professionals to prevent manifestation of the disability.

· Secondary level prevents the manifestations of additional disabilities and regression.

· Tertiary level mitigates the impact of disability on social isolation, stigmatization of the handicap.

Based on the principles of early identification and intervention, prevention of mental retardation is taken as early as possible.

Prenatal Prevention relates to

· Dealing with causal factors such as Rh incompatibility; maternal illness, infections and other high risk conditions, such as malnutrition in mother and child during the first trimester of pregnancy, environmental and occupational hazards and consanguinity.

· Prenatal diagnosis where preliminary investigations are carried out, blood and urine tests investigations to assess the foetal abnormalities through ultra sonography, radiography, and aminocentesis.

· Immunization to the mother for preventing illnesses and infections leading to disability in the foetus.

· Follow up action is provided through periodic checkups, prompt treatment and effective management plan with a balanced diet and periodic health checkups.

Natal Prevention relates to

· Delivery conducted under hygienic conditions by a trained person and/or in a hospital, to prevent breech delivery, asphyxia, prematurity with low birth weight, occurrence of jaundice, and other post-illnesses in the child.

· Care of new borns at high risk for mental retardation in well equipped neonatal intensive care units; a close follow up to identify delays and abnormalities in development; facilitating interventions and corrections at the earliest thereby reducing the severity of handicap.

Postnatal Prevention relates to

· Neonatal screening with simple blood and urine tests for metabolic abnormalities and hypothyrodisim, associated conditions that lead to mental retardation.

Prevalence

The variability in the reported prevalence of intellectual disability is explained on the basis of the differences in the definitions used in different surveys, how data was collected, and the characteristics of the populations studied. The distribution of the measured intellectual quotient (IQ) in a given population follows the typical bell shaped curve. Based on the typical distribution of the measured IQ in the population and applying 2 standard deviations below the mean as the cut-off, intellectual disability is identified in 2.5% of the general population.

According to DSM 5, the prevalence of intellectual disability is 1% of the general population; with 6 per 1,000 persons reported to have severe intellectual disability (2). Most epidemiological surveys generally categorize the severity of intellectual disability as mild (IQ ≥50) or severe (IQ ≤50), with 75% of individuals recognized to have mild intellectual disability. In the United States, the prevalence of severe intellectual disability has been reported to be between 0.3% and 0.5% of the population, which has remained unchanged for past several decades.

The worldwide reported prevalence of intellectual disability is 16.41 per 1,000 persons in low income countries; 15.41 per 1,000 persons in middle income countries; and, 9.21 per 1,000 persons in high income countries.

The male to female ratio for intellectual disability is 2:1. In a family with one child affected with severe intellectual disability, the recurrence risk for subsequent child to have intellectual disability is between 3% and 9%.

Myths and Facts

Myth: Intellectual disability is a hereditary problem.

Fact: Intellectual disability is only sometimes inherited. Most often, it is caused by external influences, some of which can be prevented.

Myth: Intellectual disability is contagious.

Fact: This is entirely false, as intellectual disability does not spread by any type of contact.

Myth: Children with intellectual disability should not be made to cry when being disciplined.

Fact: Like all children, children with intellectual disability also need to be taught good behavior. However, it is important to take their limitations into consideration while disciplining them.

Myth: Marriage can cure intellectual disability.

Fact: This is entirely false. Marriage to a person with intellectual disability must take place with the full consent of the partner, who should be informed about the medical condition of the person.

Myth: Medicines and vitamins can cure intellectual disability.

Fact: When intellectual disability is caused by a treatable condition, appropriate treatment of that condition can cure it. There are however, no tonics that can stimulate a damaged brain.

Myth: Adults with intellectual disability can pose sexual danger to others because they have poor sexual control.

Fact: Adults with intellectual disability tend to be sexually inhibited.

Myth: Bad deeds/karma of parents from a previous life can cause intellectual disability.

Fact: This is entirely false. Beliefs like these only add to the already increased burden on the parents. Intellectual disability is a medical condition, and parents and caregivers need support from the community. People with intellectual disability perform very well with sufficient support and encouragement from their family and the community.

Myth: Faith healers can cure intellectual disability.

Fact: This is completely false. Faith healers mislead parents into believing that they can cure intellectual disability. There is no proof or valid research-based evidence that supports this claim.

4.2 Classification of students with ID, learning environment and learning

Medical classification

1. Infections and intoxications

2. Trauma or physical agent

3. Metabolic or nutrition

4. Gross brain disease (post natal)

5. Unknown prenatal influence

6. Chromosomal abnormality

7. Gestational disorders

8. Psychiatric disorder

9. Environmental influences

10.Other influences

Psychological classification

Based on the 1983 AAMR definition, the operational classification for persons with mental retardation is as follows:

Educational Classification

In the special education centers in India, the classroom classification in operation is as shown below:

AAMR Levels of Support

Intermittent - Support is not always needed. It is provided on an "as needed" basis and is most likely to be required at life transitions (e.g. moving from school to work .

Limited - Consistent support is required, though not on a daily basis. The support needed is of a non-intensive nature.

Extensive - Regular, daily support is required in at least some environments (e.g. daily home-living support).

Pervasive - Daily extensive support, perhaps of a life-sustaining nature, is required in multiple environments.

It is important to know that despite difficulties in a learning environment students with intellectual disability can and do have the capacity to acquire and use new information. There is a range of inclusive teaching strategies that can assist all students to learn but there are some specific strategies that are useful in teaching a group which includes students with intellectual disability:

- Provide an outline of what will be taught - highlight key concepts and provide opportunities to practise new skills and concepts.

- Provide reading lists well before the start of a course so that reading can begin early.

- Consider tailoring reading lists and provide guidance to key texts. Allow work to be completed on an in-depth study of a few texts rather than a broad study of many.

- Whenever you are introducing procedures or processes or giving directions, for example in a laboratory or computing exercise, ensure that stages or sequences are made clear and are explained in verbal as well as written form.

- Students may benefit from using assistive technology.

- Use as many verbal descriptions as possible to supplement material presented on blackboard or overhead

- Use clear, succinct, straightforward language.

- Reinforce learning by using real-life examples and environments.

- Present information in a range of formats – handouts, worksheets, overheads, videos – to meet a diversity of learning styles.

- Use a variety of teaching methods so that students are not constrained by needing to acquire information by reading only. Where possible, present material diagrammatically - in lists, flow charts, concept maps etc.

- Keep diagrams uncluttered and use colour wherever appropriate to distinguish and highlight.

- Ensure that lists of technical/professional jargon which students will need to learn are available early in the course.

- Recording lectures will assist those students who have handwriting or coordination problems and those who write slowly as well as those who have a tendency to mishear or misquote.

- Students will be more likely to follow correctly the sequence of material in a lecture if they are able to listen to the material more than once.

- Wherever possible, ensure that key statements and instructions are repeated or highlighted in some way.

- One-to-one tutoring in subjects may be important; this can include peer tutoring.

- Students may benefit from having oral rather than written feedback on their written assignments.

- It may be helpful for students with intellectual disability to have an individual orientation to laboratory equipment or computers to minimise anxiety.

A child with an intellectual disability can do well in school but is likely to need the individualized help that’s available as special education and related services. The level of help and support that’s needed will depend upon the degree of intellectual disability involved.

General education. It’s important that students with intellectual disabilities be involved in, and make progress in, the general education curriculum. That’s the same curriculum that’s learned by those without disabilities. Be aware that IDEA does not permit a student to be removed from education in age-appropriate general education classrooms solely because he or she needs modifications to be made in the general education curriculum.

Supplementary aids and services. Given that intellectual disabilities affect learning, it’s often crucial to provide support to students with ID in the classroom. This includes making accommodations appropriate to the needs of the student. It also includes providing what IDEA calls “supplementary aids and services.” Supplementary aids and services are supports that may include instruction, personnel, equipment, or other accommodations that enable children with disabilities to be educated with nondisabled children to the maximum extent appropriate.

Thus, for families and teachers alike, it’s important to know what changes and accommodations are helpful to students with intellectual disabilities. These need to be discussed by the IEP team and included in the IEP, if appropriate.

Adaptive skills. Many children with intellectual disabilities need help with adaptive skills, which are skills needed to live, work, and play in the community. Teachers and parents can help a child work on these skills at both school and home. Some of these skills include:

· communicating with others;

· taking care of personal needs (dressing, bathing, going to the bathroom);

· health and safety;

· home living (helping to set the table, cleaning the house, or cooking dinner);

· social skills (manners, knowing the rules of conversation, getting along in a group, playing a game);

· reading, writing, and basic math; and

· as they get older, skills that will help them in the workplace.

Transition planning. It’s extremely important for families and schools to begin planning early for the student’s transition into the world of adulthood. Because intellectual disability affects how quickly and how well an individual learns new information and skills, the sooner transition planning begins, the more can be accomplished before the student leaves secondary school.

4.3 Understanding strengths and needs of learners with Intellectual Disabilities

The emergence of the science of character as an area of focus within the field of positive psychology mirrors, in many ways, shifts that have occurred within the disability field. Just as in the broader field of psychology, in the disability field there have been shifts from deficit-based models that focused on identifying limitations in functioning (Wehmeyer et al., 2008) to strengths-based approaches that recognize that people with disabilities have personal competencies that also need to be understood and leveraged to guide supports planning (Buntinx & Schalock, 2010). For example, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004) specifically states that transition services provided to youth ages 16 and over to support the transition from school to the adult world must take into account the “child’s strengths, preferences, and interests.” This mandate is driven by a growing body of research that documents strengths that are present in youth with disability that can inform the transition process (Carter, Brock, & Trainor, 2014) and be used to develop meaningful IEP and transition goals informed by strengths based assessment tools (Epstein, 2004). Similarly, researchers have asserted that systems of supports and individualized supports plans for adults with disabilities should be driven by a strengths perspective that presumes competence and designs supports accordingly, considering the person’s strengths, interests, preferences, and life goals (Buntinx, 2013).

In the general population, researchers have suggested that the use of character strengths by people in their daily lives has been associated with many positive outcomes and that understanding one’s character strengths can serve as a means to build systems of supports to overcome barriers. Work is needed to develop strategies to enable people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to understand their character strengths and to embed these character strengths in educational and support provision. For example, existing exercises like strengths-spotting, “use your signature strengths in new ways each day” (Seligman et al., 2005), “counting kindness” (Otake et al., 2006), and “gifts of time” (Gander et al., 2012), could easily be integrated into educational and community contexts particularly if resources for educators, support providers, and family members were developed. Although research is needed, such interventions may address provide a way to address issues commonly identified related to building relationships between people with intellectual disability and their peers, as people with disabilities are often cast in roles of needing help, rather than giving help, limiting reciprocal relationships (Snell & Brown, 2010). However, by creating structured ways for people with intellectual disability to use their strengths to contribute to the lives of their peers, the reciprocity of peer relationships could be enhanced.

Overall, there are multiple applications of strategies that build on character strengths that can enhance the systems of supports and outcomes experienced by people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. The preceding examples offer several ways that activities and research in positive psychology and related fields could be adapted and applied to the contexts within which people with intellectual and developmental disabilities live their lives. However, systematic development and evaluation of these approaches is needed in the intellectual and developmental disability field, and guidelines developed and evaluated to adapt such approaches to people with varying ranges of support needs.

► Children with ID demonstrate strengths and weaknesses in executive functioning.

► Children with ID show mental age appropriate fluency and switching.

► Children with ID have problems with inhibition and planning.

► Children with ID have problems with verbal executive-loaded working memory.

► Mental age and experience are differently related to different executive functions.

4.4 Learning characteristics, Cognitive process, Sequential processing of information in children with ID

Academic Performance

Students identified with intellectual disabilities fail to keep up the grade level of peers in developing academic skills. These students are slow in learning to read and in learning basic math skills. These students also have delayed language skills which also affect other academic areas such as writing, spelling, and science. Taylor, Richards, & Brady, 2005

Cognitive Performance

Cognition covers three aspects such as attention, memory, and generalization.

- Attention: Students have difficulty in attending such as they should be “Orienting to a task means they should focus on the direction of the task whereas they should have selective attention means that they should only focus on the relevant tasks not on unimportant tasks and sustained attention means that continue the task for the period of time. But students with intellectual difficulties can’t attain these attentions.

- Memory: these students also have difficulty remembering the information, for example, they may have problems remembering the math facts or spellings or if they remember this information one day, they may forget it the next day.

- Generalization: final area in which students with intellectual disabilities may have difficulty is to generalize the information to other material or settings for example he may learn a new word in one subject area but in learning the same word in another subject may have difficulty. Smith et al., 2004

Social Skills Performance

The cognitive characteristics of students with intellectual disabilities can also cause difficulty interacting socially. For example, a low level of cognitive development and slow language development can cause a student to have a problem in understanding verbal communications and expectations likewise difficulty in attention and difficulty with memory can also affect the social interactions of students in such a way that he may not able to attend the important parts of social interactions, maintaining attention, and holding important things which they observe in their short-term memory.

Students with

intellectual disabilities vary widely in their abilities. Typical

characteristics include:

- mild to significant weaknesses in general learning ability

- low achievement in all academic areas

- deficits in memory and motivation

- inattentive/distractible

- poor social skills

- deficits in adaptive behavior

- some may exhibit uncommon characteristics (self-stimulatory or self-injurous behavior)

- some may have serious medical conditions

Sequential processing involves converting complex information into serial structures and vice versa, or converting serial structures from one format into another. Two fundamental and mutually orthogonal aspects are relevant for investigating sequential processing: the nature of the sequence to be processed and the cascade of cognitive and motor processes acting on the information in the sequence.

It is often said that people with an intellectual disability need to ‘learn, learn and overlearn’. This means that they may require many opportunities to practice concepts and skills in order for them to understand and retain the information to draw upon into the future.

Individuals with intellectual disabilities (ID, formerly mental retardation) benefit from the same teaching strategies used to teach people with other learning challenges. This includes learning disabilities, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and autism.

One such strategy is to break down learning tasks into small steps. Each learning task is introduced, one step at a time. This avoids overwhelming the student. Once the student has mastered one step, the next step is introduced. This is a progressive, step-wise, learning approach. It is characteristic of many learning models. The only difference is the number and size of the sequential steps.

A second strategy is to modify the teaching approach. Lengthy verbal directions and abstract lectures are ineffective teaching methods for most audiences. Most people are kinesthetic learners. This means they learn best by performing a task "hands-on." This is in contrast to thinking about performing it in the abstract. A hands-on approach is particularly helpful for students with ID. They learn best when information is concrete and observed. For example, there are several ways to teach the concept of gravity. Teachers can talks about gravity in the abstract. They can describe the force of gravitational pull. Second, teachers could demonstrate how gravity works by dropping something. Third, teachers can ask students directly experience gravity by performing an exercise. The students might be asked to jump up (and subsequently down), or to drop a pen. Most students retain more information from experiencing gravity firsthand. This concrete experience of gravity is easier to understand than abstract explanations.

Third, people with ID do best in learning environments where visual aids are used. This might include charts, pictures, and graphs. These visual tools are also useful for helping students to understand what behaviors are expected of them. For instance, using charts to map students' progress is very effective. Charts can also be used as a means of providing positive reinforcement for appropriate, on-task behavior.

A fourth teaching strategy is to provide direct and immediate feedback. Individuals with ID require immediate feedback. This enables them to make a connection between their behavior and the teacher's response. A delay in providing feedback makes it difficult to form connection between cause and effect. As a result, the learning point may be missed.

4.5 Level of intellectual disability and its relevance to learning characteristics.

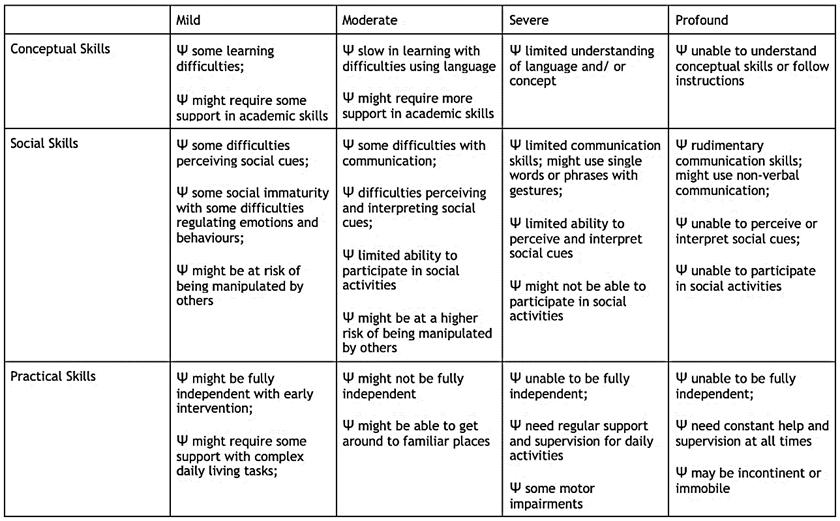

Mild intellectual disability

- IQ 50 to 70

- Slower than typical in all developmental areas

- No unusual physical characteristics

- Able to learn practical life skills

- Attains reading and math skills up to grade levels 3 to 6

- Able to blend in socially

- Functions in daily life

About 85 percent of people with intellectual disabilities fall into the mild category and many even achieve academic success. A person who can read, but has difficulty comprehending what he or she reads represents one example of someone with mild intellectual disability.

Moderate intellectual disability

- IQ 35 to 49

- Noticeable developmental delays (i.e. speech, motor skills)

- May have physical signs of impairment (i.e. thick tongue)

- Can communicate in basic, simple ways

- Able to learn basic health and safety skills

- Can complete self-care activities

- Can travel alone to nearby, familiar places

People with moderate intellectual disability have fair communication skills, but cannot typically communicate on complex levels. They may have difficulty in social situations and problems with social cues and judgment. These people can care for themselves, but might need more instruction and support than the typical person. Many can live in independent situations, but some still need the support of a group home. About 10 percent of those with intellectual disabilities fall into the moderate category.

Severe intellectual disability

- IQ 20 to 34

- Considerable delays in development

- Understands speech, but little ability to communicate

- Able to learn daily routines

- May learn very simple self-care

- Needs direct supervision in social situations

Only about 3 or 4 percent of those diagnosed with intellectual disability fall into the severe category. These people can only communicate on the most basic levels. They cannot perform all self-care activities independently and need daily supervision and support. Most people in this category cannot successfully live an independent life and will need to live in a group home setting.

Profound intellectual disability

- IQ less than 20

- Significant developmental delays in all areas

- Obvious physical and congenital abnormalities

- Requires close supervision

- Requires attendant to help in self-care activities

- May respond to physical and social activities

- Not capable of independent living

People with profound intellectual disability require round-the-clock support and care. They depend on others for all aspects of day-to-day life and have extremely limited communication ability. Frequently, people in this category have other physical limitations as well. About 1 to 2 percent of people with intellectual disabilities fall into this category.

According to the new DSM-V, though, someone with severe social impairment (so severe they would fall into the moderate category, for example) may be placed in the mild category because they have an IQ of 80 or 85. So the changes in the DSM-V require mental health professionals to assess the level of impairment by weighing the IQ score against the person's ability to perform day-to-day life skills and activities.