Unit 3: Assessment of individuals with ASD

3.1. Screening and Diagnosis: Criteria and Tools (e.g., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) 5, International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10). International Classification of Functioning (ICF) Checklist, Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (MCHAT- R/F), Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISAA), AIIMS-Modified INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Autism Spectrum Disorder (AIIMS Modified INDT- ASD). Childhood Autism Rating Scale 2nd edition (CARS-2),

3.2. Assessments of Learning Styles and Strategies (Behavioural, Functional, adaptive, Educational, and vocational)

3.3. Differential Diagnosis

3.4. Assessment of associated conditions

3.5. Documentation of assessment, interpretation and report writing

3.1 Screening and Diagnosis: Criteria and Tools (e.g., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) 5, International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10). International Classification of Functioning (ICF) Checklist, Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (MCHAT- R/F), Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISAA), AIIMS-Modified INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Autism Spectrum Disorder (AIIMS Modified INDT- ASD). Childhood Autism Rating Scale 2nd edition (CARS-2),

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) 5

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association released the fifth edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The DSM-5 is now the standard reference that healthcare providers use to diagnose mental and behavioral conditions, including autism.

A. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive, see text):

1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

3. Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

Specify current severity: Severity is based on social communication impairments and restricted repetitive patterns of behavior. (See table below.)

B. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive; see text):

1. Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypies, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

2. Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns or verbal nonverbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat food every day).

3. Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g, strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interest).

4. Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

Specify current severity: Severity is based on social communication impairments and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior. (See table below.)

C. Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities or may be masked by learned strategies in later life).

D. Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

E. These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder frequently co-occur; to make comorbid diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability, social communication should be below that expected for general developmental level.

Note: Individuals with a well-established DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified should be given the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Individuals who have marked deficits in social communication, but whose symptoms do not otherwise meet criteria for autism spectrum disorder, should be evaluated for social (pragmatic) communication disorder.

Specify if:

- With or without accompanying intellectual impairment

- With or without accompanying language impairment

- (Coding note: Use additional code to identify the associated medical or genetic condition.)

- Associated with another neurodevelopmental, mental, or behavioral disorder

- (Coding note: Use additional code[s] to identify the associated neurodevelopmental, mental, or behavioral disorder[s].)

- With catatonia

- Associated with a known medical or genetic condition or environmental factor

Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder

Diagnostic Criteria

A. Persistent difficulties in the social use of verbal and nonverbal communication as manifested by all of the following:

1. Deficits in using communication for social purposes, such as greeting and sharing information, in a manner that is appropriate for the social context.

2. Impairment of the ability to change communication to match context or the needs of the listener, such as speaking differently in a classroom than on the playground, talking differently to a child than to an adult, and avoiding use of overly formal language.

3. Difficulties following rules for conversation and storytelling, such as taking turns in conversation, rephrasing when misunderstood, and knowing how to use verbal and nonverbal signals to regulate interaction.

4. Difficulties understanding what is not explicitly stated (e.g., making inferences) and nonliteral or ambiguous meanings of language (e.g., idioms, humor, metaphors, multiple meanings that depend on the context for interpretation).

B. The deficits result in functional limitations in effective communication, social participation, social relationships, academic achievement, or occupational performance, individually or in combination.

C. The onset of the symptoms is in the early developmental period (but deficits may not become fully manifest until social communication demands exceed limited capacities).

D. The symptoms are not attributable to another medical or neurological condition or to low abilities in the domains or word structure and grammar, and are not better explained by autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder), global developmental delay, or another mental disorder.

International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10)

Pervasive developmental disorders

A group of disorders characterized by qualitative abnormalities in reciprocal social interactions and in patterns of communication, and by a restricted, stereotyped, repetitive repertoire of interests and activities. These qualitative abnormalities are a pervasive feature of the individual's functioning in all situations.

Childhood autism

A type of pervasive developmental disorder that is defined by: (a) the presence of abnormal or impaired development that is manifest before the age of three years, and (b) the characteristic type of abnormal functioning in all the three areas of psychopathology: reciprocal social interaction, communication, and restricted, stereotyped, repetitive behaviour. In addition to these specific diagnostic features, a range of other nonspecific problems are common, such as phobias, sleeping and eating disturbances, temper tantrums, and (self-directed) aggression.

Autistic disorder

Infantile:

· autism

· psychosis

Kanner syndrome

Atypical autism

A type of pervasive developmental disorder that differs from childhood autism either in age of onset or in failing to fulfil all three sets of diagnostic criteria. This subcategory should be used when there is abnormal and impaired development that is present only after age three years, and a lack of sufficient demonstrable abnormalities in one or two of the three areas of psychopathology required for the diagnosis of autism (namely, reciprocal social interactions, communication, and restricted, stereotyped, repetitive behaviour) in spite of characteristic abnormalities in the other area(s). Atypical autism arises most often in profoundly retarded individuals and in individuals with a severe specific developmental disorder of receptive language.

· Atypical childhood psychosis

· Mental retardation with autistic features

Rett syndrome

A condition, so far found only in girls, in which apparently normal early development is followed by partial or complete loss of speech and of skills in locomotion and use of hands, together with deceleration in head growth, usually with an onset between seven and 24 months of age. Loss of purposive hand movements, hand-wringing stereotypies, and hyperventilation are characteristic. Social and play development are arrested but social interest tends to be maintained. Trunk ataxia and apraxia start to develop by age four years and choreoathetoid movements frequently follow. Severe mental retardation almost invariably results.

Other childhood disintegrative disorder

A type of pervasive developmental disorder that is defined by a period of entirely normal development before the onset of the disorder, followed by a definite loss of previously acquired skills in several areas of development over the course of a few months. Typically, this is accompanied by a general loss of interest in the environment, by stereotyped, repetitive motor mannerisms, and by autistic-like abnormalities in social interaction and communication. In some cases the disorder can be shown to be due to some associated encephalopathy but the diagnosis should be made on the behavioural features.

· Dementia infantilis

· Disintegrative psychosis

· Heller syndrome

· Symbiotic psychosis

Overactive disorder associated with mental retardation and stereotyped movements

An ill-defined disorder of uncertain nosological validity. The category is designed to include a group of children with severe mental retardation (IQ below 35) who show major problems in hyperactivity and in attention, as well as stereotyped behaviours. They tend not to benefit from stimulant drugs (unlike those with an IQ in the normal range) and may exhibit a severe dysphoric reaction (sometimes with psychomotor retardation) when given stimulants. In adolescence, the overactivity tends to be replaced by underactivity (a pattern that is not usual in hyperkinetic children with normal intelligence). This syndrome is also often associated with a variety of developmental delays, either specific or global. The extent to which the behavioural pattern is a function of low IQ or of organic brain damage is not known.

Asperger syndrome

A disorder of uncertain nosological validity, characterized by the same type of qualitative abnormalities of reciprocal social interaction that typify autism, together with a restricted, stereotyped, repetitive repertoire of interests and activities. It differs from autism primarily in the fact that there is no general delay or retardation in language or in cognitive development. This disorder is often associated with marked clumsiness. There is a strong tendency for the abnormalities to persist into adolescence and adult life. Psychotic episodes occasionally occur in early adult life.

· Autistic psychopathy

· Schizoid disorder of childhood

Other pervasive developmental disorders

Pervasive developmental disorder, unspecified

International Classification of Functioning (ICF) Checklist

With a current worldwide prevalence of 1% Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) refers to a group of conditions that are characterized by impairments of reciprocal social interaction, verbal and non-verbal communication, as well as a preference for repetitive, stereotyped activities, behaviors and interests. The age of onset is always prior to 36 months and the symptoms persist throughout the lifespan. These features are associated with alternations in cognitive and emotional functioning, high rates of psychiatric co-morbidity, relationship problems, poor adaptive skills and lower reported quality of life. To capture this complex melange of functioning experiences beyond the diagnosis, the ICF offers a tool to describe the lived experience of a person with ASD in a comprehensive and standardized way.

To make the ICF, a classification of 1424 categories, more practical for use in clinical practice, ICF Core Sets i.e. shortlists of ICF categories selected as most relevant for specific health conditions, have been developed. Karolinska Institute and the ICF Research Branch in collaboration with an international, multiprofessional Steering Committee have taken on the challenge to develop ICF Core Sets that can be used in the assessment and follow-up of persons with ASD. The project team has decided to use the ICF version for children and youth (ICF-CY) for the study. The ICF-CY not only includes all of the categories of the reference classification ICF, it also captures the particular characteristics of the developing child.

The preparatory phase includes:

- To identify research studies on the functioning and disability of persons with ASD, a systematic literature review of peer-reviewed articles published from 2008-2013 was performed.

- A qualitative study that aimed to identify relevant aspects of functioning and contextual factors from the perspective of patients/clients, caregivers, spouses, teachers was conducted. Persons from Canada, India, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Sweden participated in the study either in focus groups or individual interviews. A manuscript is currently being written and will be submitted to a peer-review journal by the end of 2016.

- An internet-based international survey was also conducted. This study that included 225 experts from 10 different disciplines and all six WHO world regions aimed to gather the opinion of international experts on which aspects of functioning and health are relevant to persons with ASD.

- To describe common problems experienced by individuals with ASD from a clinical perspective, a multicentre cross-sectional study was conducted in 6 European countries, 2 South American countries, one Asian country, and one country in the Middle East. A case record form, that covered among other things the domains of an extended ICF Checklist, was used to collect the data.

Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (MCHAT- R/F)

The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised (M-CHAT-R) is a screener that will ask a series of 20 questions about your child’s behavior. It's intended for toddlers between 16 and 30 months of age. The results will let you know if a further evaluation may be needed. You can use the results of the screener to discuss any concerns that you may have with your child’s healthcare provider.

The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) was designed to screen for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children between 16 months and 30 months. Validation studies have reported moderate psychometric properties across various populations, potentially supporting the use of the M-CHAT as part of universal screening. The purpose of ASD screening using a standardized tool is to systematically identify early signs of ASD, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that it should take place at 18 months and 24 months for all children. Whether screening should take place for all children and with which screening tool, however, are currently being debated.

The original M-CHAT consists of 23 questions about behaviors that are potential early signs of ASD in very young children. Parents or caregivers complete the checklist on the basis of their child's current skills and behaviors. Its brevity is one of its advantages, as is the fact that it does not require responses based on clinical observation by a trained clinician. A child is considered to be at-risk if they fail more than two of the six critical items (Critical6) or three of the 23 items (Total23) on the checklist. Among the 1293 children screened in the original study, 132 screened positive and 39 were later diagnosed with ASD. The M-CHAT follow-up interview, a 5- to 20-minute structured telephone interview used to confirm items endorsed by the parent, can be performed in addition for children who screen positive before full developmental assessment. The follow-up interview was reported to improve positive predictive value (PPV). A revised with follow-up version, M-CHAT-R/F, excluded three items from the original M-CHAT and was validated in a low-risk sample with a PPV of 0.14.

The M-CHAT™ (Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers) is a parent-report screening tool to assess the risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). In approximately 10 minutes, parents can complete the 20 questions and receive an autism risk assessment for their child.

Age of Child: The M-CHAT is most appropriate for 16 to 30 month old children.

The primary goal of M-CHAT is to detect as many cases of ASD as possible (“maximizing sensitivity” in scientific parlance), so there will be some false-positives: cases where a child is assessed as being “at risk” but in fact will not be diagnosed with ASD. However, any child that receives a “high-risk” score should receive an evaluation from an autism specialist.

Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISAA)

Though autism is a well documented developmental disability, most of the screening and diagnostic tools for assessment and diagnosis of autism are intended for western population. As one cannot undermine the importance of cultural influence in the understanding of any disorder or disability, it was imperative that a tool for assessment of persons with autism be developed considering the Indian socio-cultural context. ISAA is an individually administered instrument which encompasses six domains measuring the characteristic triad of impairments in social relationship, communication and behavior patterns of persons with autism. The test items of the tool were constructed from the range of activities generally performed by the persons with autism. Comparison group of normal and individuals with mental retardation & other psychiatric illnesses were tested to determine the uneven development characteristic of this type of disability.

Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISAA): The ISAA is a 40 item scale divided into six domains- Social Relationship and Reciprocity (9 questions); Emotional Responsiveness (5 questions); Speech — Language and Communication (9 questions); Behavior Patterns (7 questions); Sensory Aspects (6 questions) and Cognitive Component (4 questions). The scores for the each item of ISAA range from 1-5, depending on the intensity, frequency and duration of a particular behavior with the following anchors: score 1 = Rarely (up to 20%), score 2 = Sometimes (21-40%), score 3 = Frequently (41-60%), score 4 = Mostly (61-80%), and score 5 = Always (81%-100%). Scoring is based on information from parents and observation of the child following guidelines from the Manual of the ISAA. In the speech- language and communication domain the child should be rated 5 if he/she never developed speech or communication. Total ISAA scores range from 40-200. The lowest score represents no symptoms or symptoms which were present only rarely, and the maximum score indicates the most severe presentation of AD. The following categories are recommended; mild AD: 70-107, moderate AD: 108-153, severe AD: 153.

AIIMS-Modified INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Autism Spectrum Disorder

The Modified INCLEN tool was validated by a team of experts by modifying the existing tools (2–9 years) to widen the age range from 1 month to 18 years and include broader symptomatology in a tertiary care teaching hospital of North India between January and June 2015. A qualified medical graduate applied the candidate tool which was followed by gold standard evaluation by a Pediatric Neurologist (both blinded to each other).

The construct and its sub-construct were adapted for its appropriateness in the Indian cultural context and converted into symptoms clusters for the clinicians and psychologists to rate during the diagnostic workup. The tool was named as INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for ASD (INDT-ASD). The tool has two sections: Section A has 29 symptoms/items and Section B contains 12 questions corresponding to B and C domains of DSM-IV-TR, time of onset, duration of symptoms, score and diagnostic algorithm. It takes approximately 45-60 minutes to administer the instrument and score. A trichotomous endorsement choice (‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unsure/not applicable’) is given to the assessor/ interviewer. In addition, the clinician/psychologist has to make behavioral observations on the child and score the item as well. For any discrepancy in parental response and interviewer’s assessment, it is indicated for each question whether parental response or assessor’s observation should take precedence. Each symptom/item is given a score of ‘1’ for ‘Yes’ and ‘0’ for ‘No’ or ‘unsure/not applicable’. Presence of ³ 6 symptoms/item (or score of ³ 6), with at least two symptom/item each from impaired communication and restricted

|

repetitive pattern of behavior, is used to diagnose ASD.

Childhood Autism Rating Scale 2nd edition (CARS-2)

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale–Second Edition (CARS2) is a 15-item rating scale used to identify children with autism and distinguishing them from those with developmental disabilities. It is empirically validated and provides concise, objective, and quantifiable ratings based on direct behavioral observation. It was normed on a sample of 1,034 individuals with autism spectrum disorders.

This second edition of CARS expands the test’s clinical value, making it more responsive to individuals on the “high functioning” end of autism spectrum disorders. The clinician rates the individual on each item, using a 4-point rating scale. Ratings are based on frequency of the behavior in question, its intensity, peculiarity, and duration.

Physicians, special educators, school psychologists, speech pathologists, and audiologists will all find the CARS-2 easy to give and score.

The CARS-2 includes three forms:

1. Standard Version Rating Booklet (CARS2-ST): Equivalent to the original CARS; for use with individuals younger than 6 years of age and those with communication difficulties or below-average estimated IQs

2. High-Functioning Version Rating Booklet (CARS2-HF): An alternative for assessing verbally fluent individuals, 6 years of age and older, with IQ scores above 80

3. Questionnaire for Parents or Caregivers (CARS2-QPC): An unscored scale that gathers information for use in making CARS2ST and CARS2-HF ratings

The standard and high-functioning forms each include 15 items addressing the following functional areas:

- Relating to People

- Imitation (ST); Social-Emotional Understanding (HF)

- Emotional Response (ST); Emotional Expression and Regulation of Emotions (HF)

- Body Use

- Object Use (ST); Object Use in Play (HF)

- Adaptation to Change (ST); Adaptation to Change/Restricted Interests (HF)

- Visual Response

- Listening Response

- Taste, Smell, and Touch Response and Use

- Fear or Nervousness (ST); Fear or Anxiety (HF)

- Verbal Communication

- Nonverbal Communication

- Activity Level (ST); Thinking/Cognitive Integration Skills (HF)

- Level and Consistency of Intellectual Response

- General Impressions

The parent or caregiver of the individual being assessed completes this unscored form. Its primary purpose is to give the clinician more information on which to base the CARS2-ST or CARS2-HF ratings. The questionnaire covers an individual’s early development; social, emotional, and communication skills; repetitive behaviors; play and routines; and unusual sensory interests.

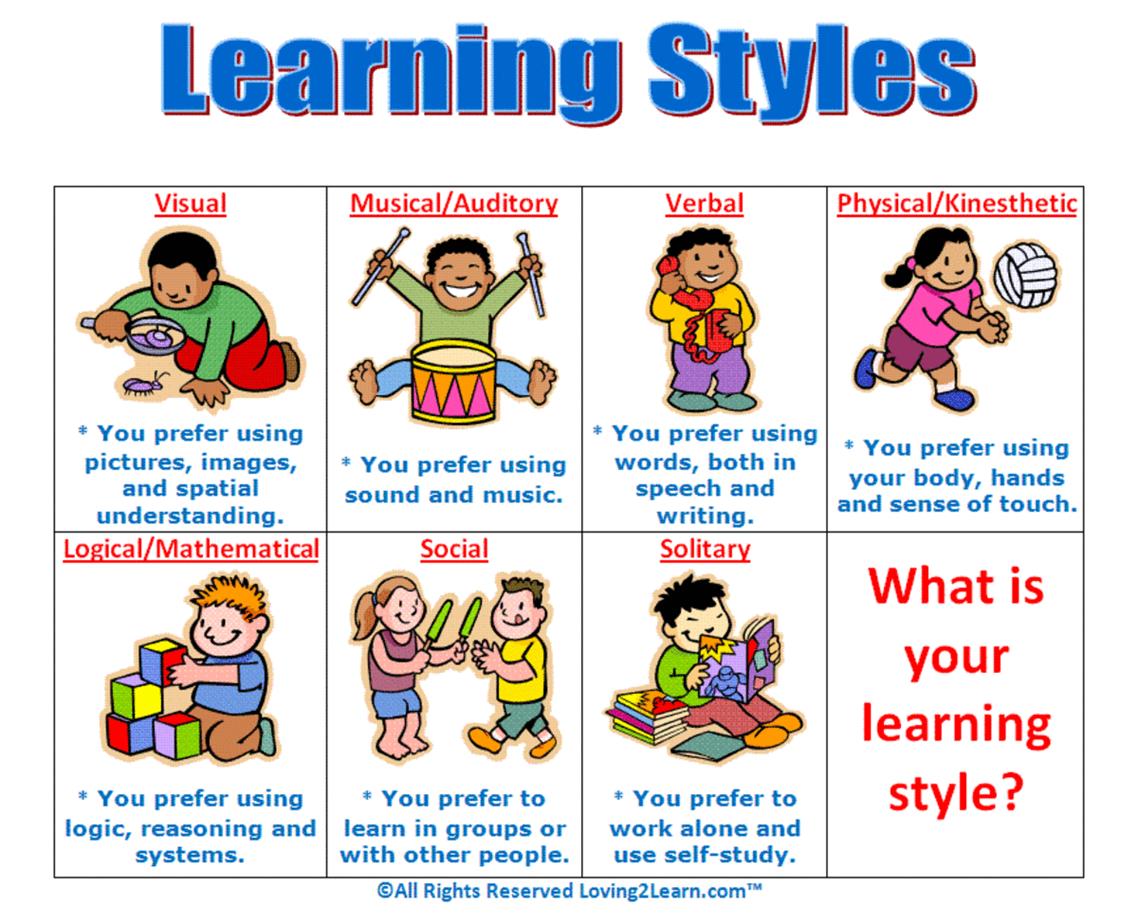

3.2 Assessments of Learning Styles and Strategies (Behavioural, Functional, adaptive, Educational, and vocational)

Teachers need to find out how their students learn. There are three main different learning styles: visual, auditory, and tactile/kinesthetic learners. In order to assess students’ learning, you can give them a learning styles assessment at the beginning of the school year. Not only will this help the teacher, but it gives the students insight into how they learn. Here is a simple assessment that you can do. The easiest way to do it is to separate the assessment into three sections, each for the different learning styles, but don’t tell the students which section is which.

Styles of Learning

We define a learning modality as a sensory pathway in which students learn. They take in, share, and store information through their modalities or learning styles. There are many opinions about the quantity of learning styles. Most educators agree on these three as styles of learning found in most classrooms:

- Visual learners like to see things and understand spatial relationships

- Auditory learners prefer to hear lessons

- Kinesthetic/tactile learners like using the body for learning

Visual, auditory, and kinesthetic/tactile are the three learning modalities. You may not be aware of the impact your learning style has on your experiences, both in and out of the classroom. How can you figure out your learning style?

What's Your Modality?

Using your strengths as a teacher can help accommodate styles of learning in your students. How can you determine your own learning modality? Think of yourself in these situations.

- Spelling - When trying to spell a new word, do you try to picture the word (visual), use your phonics skills to rely on letters and sounds (auditory), or write the word down (kinesthetic/tactile)?

- Bumping into an acquaintance - When you bump into someone you met once or twice, are you good at remembering the faces but not names (visual), remember names but not faces (auditory), or remember the things you did with this person (kinesthetic/tactile)?

- Doing something new - Do you need to see diagrams or pictures (visual), need verbal instructions (auditory), or do you prefer to just get busy and figure it out as you go (kinesthetic/tactile)?

- Receiving information from administration - When your principal wants to give you information, do you prefer to read it in a memo or email (visual), hear it in a voicemail (auditory), or attend a face-to-face meeting (kinesthetic/tactile)?

Why Should We Assess Our Student's Learning Styles?

The people that we encounter in life are usually different than we are and likewise have experienced different things than we have. In fact, it can be said that the same is true of the learning process. Everyone learns differently, therefore it would seem to make sense that schools adjust according to this. However, this has not been the case. In general, educators have been accustomed to grouping students into two tracks- linguistic and mathematical. In the process, educators may fail to recognize that students learn differently, therefore instruction should be adjusted to accommodate these needs. Tomlinson (1999) states that educators should meet a student at his or her level in order to maximize potential. This, however, has not been the case up to this point. Instead, education is geared to teaching to linguistic abilities (Peterson, 1994). In the essence, the current system does not seem to accommodate the needs of all learners. Oftentimes, the children who do not do well linguistically, are the same children who do not do well in school (Peterson, 1994). The literature suggests (Campbell, Milbourne, & Silverman, 2001; Williams, 1983; & Armstrong, 2001) that children who do not fit into this continuum are those left behind. In fact, many of these same children are viewed as having a weakness, thus this results in them being placed in special classrooms (Tomlinson, 1999).

Assessment practices may need to focus on adapting instruction to include the different ways a student learns. It is necessary to assess the strengths and limitations of young children, as this may provide useful information before a child enters school (Buffalo University). Assessments can be a desired tool to help meet students before they begin developing problems. However, it is suggested that a good assessment will include information on what a child knows, what the child can do, how the child learns, and where any concerns or problems lie (Rudolph, 1999).

3.3 Differential Diagnosis

As the name implies, Autism Spectrum Disorder is a varied condition, that means, the above clinical features are present on a continuum with very mild impairment at the top end of the scale to more severe impairment of the above functions at the bottom end.

More importantly, there are several clinical conditions, described below, that share some the features of ASD. Hence it is unsurprising that they can mistakenly be labelled as ASD. To complicate things further, many of the below-mentioned conditions can commonly co-occur with ASD. Therefore, as you can appreciate, because of the complexities involved, even the experts can get it wrong.

Moreover, as ASD is a lifelong diagnosis and since a wrong diagnosis can lead to suboptimal or poor outcomes for the child and the family, it becomes imperative to undertake a detailed evaluation to arrive at the diagnosis of ASD, and to rule out the possibility of the below-mentioned conditions that can mimic as ASD.

Differential diagnosis simply means that there is more than one possibility for a diagnosis. Oxford Dictionary describes ‘differential diagnoses’ (plural noun) as ‘the process of differentiating between two or more conditions which share similar signs or symptoms.’

Some conditions may be confusingly similar to ASD and one must be careful when making a final determination about a child’s disorder and its management. Any condition that may be associated with language delay, especially those that are treatable, must be considered.

Following are some of the conditions that can mimic or present as ASD. I have listed them in no particular order. However, conditions in the top half of the list need to be considered more often than the conditions in the bottom half.

1. Learning Disability/Intellectual Disability (LD/ID): Learning disability is the term more commonly used in the UK (and our colleagues in the US, use the term ID or intellectual disability), for any child with significant global developmental delay. Reflecting on my experience, LD/ID must be at the top of my list because of at least two crucial reasons. Firstly, many children with ASD can have a degree of LD, making the need for carrying out a developmental assessment as part of ASD evaluation, vital. Second, it is common to get children with LD confused as having ASD, as children with LD engage in repetitive behaviours for a variety of reasons. Carrying out a developmental assessment will reveal that the language abilities of children with LD are in keeping with their cognitive ability. Moreover, children with LD have better non-verbal communication ability and a reasonable degree of emotional reciprocity, while children with ASD do not.

2. ADHD: It is common for children with ASD to be confused with ADHD. Temper tantrums and repetitive behaviours can be mistaken with hyperactivity. And avoidance of eye contact can be confused with inattention. However, children with ADHD are likely to be impulsive and domineering. They have better abilities for imaginative play and have the intent to communicate their needs. Children with ASD, on the other hand, are likely to be remote, aloof and have impaired intent and ability to communicate their needs. It is crucial to remember that both ASD and ADHD can co-occur.

3. Social Communication Disorder (SCD): It is easy to confuse children with SCD as having ASD because children in both these conditions have impaired verbal and non-verbal communication abilities. However, as DSM-5 manual has specified, unlike children with ASD, SCD children do not have restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour and activities.

4. Gifted and Talented: Children who are gifted and talented have high intelligence and incredibly good memory. These children, when they have co-existing anxiety, can mimic ASD. Nevertheless, children who are gifted and talented seek social interactions and have good ability to understand and use language appropriate to social context.

5. Anxiety: Anxiety can be a common co-morbidity in children with ASD. Children with a social anxiety disorder or selective mutism can have several features that overlap with ASD. However, unlike children with ASD, these children have good imaginative play skills and are better able to communicate their needs to their parents and carers.

6. Language Disorder: Children with language disorder differ from ASD, in that, they have better motivation and intention to communicate their needs. Their non-verbal communication abilities are not impaired to the same extent as children with ASD. Also, unlike ASD, they have a better imaginative play.

7. Hearing Impairment: It is common for parents of children with ASD, to wonder whether their child is deaf or hearing impaired. This is because, like children with ASD, children with hearing impairment display a lack of response to their name being called, have minimal babbling, and have difficulty in using language to communicate their needs. But unlike ASD, children with hearing impairment can have a good imaginative play, have good eye contact, and can express themselves with a range of gestures, facial expressions, and body language.

8. Attachment Disorder: A history of significant parental deprivation and or neglect in early months and years is an important feature in the history of children with attachment disorder, that is absent in children with ASD. Also, children with attachment disorder develop their social interaction and language abilities when they are placed in a suitable caregiving environment.

9. Regression and Rett’s: The term ‘regression’ is used, when there is a history of a child losing hand skills and or speech and language abilities, they had previously acquired. This can understandably be genuinely concerning to parents. Rett’s syndrome is a clinical condition that occurs specifically in girls, because of a mutation in a specific gene called MECP2. In this condition, girls who appeared to be developing typically, lose speech and their ability to use hands for daily activities. Rett’s syndrome, along with childhood disintegrative disorder, are no longer classed under Autism Spectrum Disorder when DSM was revised, in 2013.

10.Genetic disorders and Syndromic: There are over a dozen syndromes that have overlapping features with ASD. Also, ASD tends to occur more commonly with certain conditions such as Fragile X, Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Down Syndrome, etc. A detailed assessment by a neurodevelopmental paediatrician can identify these conditions.

11.Inherited Metabolic Disorder (IMD): Children with disorders of carbohydrate and protein metabolism could present with a learning disability, hearing impairment, vision impairment, developmental regression, and food intolerance. Presence of an IMD in children with ASD is fortunately rare.

12.Epilepsy: Certain epilepsy such as Landau Kleffner Syndrome (LKS), though rare, can present with the child losing the ability to understand language, display behavioural outbursts and have temper tantrums. An EEG (electroencephalogram/tracing of the brain) can help identify seizures, as the cause of ASD like symptoms.

13.Tourette’s: Children with Tourette’s syndrome and accompanying ADHD symptoms can be misinterpreted to have ASD, because of impaired social interaction skills and social communication skills secondary to sudden utterances, brief but repetitive tics, etc.

14.Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): Both ASD and OCD can have similar symptoms. However, unlike ASD, children with OCD have better social interaction and social communication skills. Also, unlike children with ASD, children with OCD tend to find their symptoms distressing.

15.Sensory Processing Difficulties (SPD): SPD was not part of the diagnostic criteria for ASD until the latest revision to DSM in 2013. Inclusion of SPD as one of the features for the diagnosis of ASD has been helpful, as I encounter some degree of sensory difficulties almost universally in children with ASD. Children with SPD can be either hypersensitive or hyposensitive to a variety of sensations of sound, sight, smell, touch, and movement. Hence, children with SPD can be sensory seeking or extremely avoidant of certain sensations, resulting in some to mistakenly think them as having ASD. SPD is not recognised as a separate clinical disorder in DSM-5.

16.Vision Impairment (VI): Children with vision impairment can have features that mimic ASD because of certain qualitative differences in their social approach, social interaction, communication, and restrictive behaviours. However, it is important to note that VI and ASD can co-occur.

As you can see, the above list includes many conditions that need to be thought of, considered, and ruled out, before a diagnosis of ASD can be made. Nevertheless, this list is by no means exhaustive. Therefore, a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation is essential for an accurate diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder.

3.4 Assessment of associated conditions

Despite the heterogeneity of ASD manifestations in affected children, they share core deficits delineated in the DSM-5 of the American Psychiatric Association. It includes descriptors of ASD symptoms with severity level criteria and symptoms of social (pragmatic) communication disorder (SPCD) although without assigned severity levels. A diagnosis of ASD requires evidence of impairment in three features of social communication and social interaction and two features of restricted repetitive patterns of behavior (RRPB). Symptoms must be present in early development and cause impaired everyday function. Both social communication and social interaction, and RRPB severity levels are based on the degree of support the individual needs in order to function: mild, substantial, and very substantial support. The diagnosis should also specify presence or absence of accompanying intellectual impairment, language impairment, or whether there are associated known medical, genetic, or other conditions.

Often in children with autism there are signs and symptoms which are not readily explained by a diagnosis of autism alone. Other medical and psychiatric conditions may co-exist with autism including;

1. Learning difficulties

2. Epilepsy

3. Speech and Language problems

4. Attention Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

5. Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD)

6. Tourette’s Syndrome and Tics

7. Feeding and Eating problems

This is not an exhaustive

list, but we will briefly consider some of the most common conditions and

difficulties that a child with autism may also be diagnosed with.

Learning Difficulties: As noted above, approximately 70% of

children with classic autism also have an IQ below 70 and are therefore

recognised to have mild, moderate or severe learning difficulties.

Epilepsy: As with learning difficulties, epilepsy is more common

among children diagnosed with classic autism, with around 30% being affected

into adulthood. Epilepsy is less common among children with Asperger’s

Syndrome, but may be more prevalent than in typically developing children.

Speech and Language Problems: Most children with an ASD have slower

language development than their peers. It is not only expressive language that

may show problems, receptive language may also appear delayed in young children,

and children may appear to be less responsive to their own name. Some children

with autism also appear to lose words that they had previously learnt. This

regression is described in approximately 25% of children with classic autism,

and is usually a gradual process where a child fails to learn new words, and

may stop using previously learnt words altogether.

ADHD: ADHD is the most common psychiatric disorder to occur

alongside an ASD and there are clinical benefits from receiving a dual

diagnosis. Children are likely to benefit from receiving treatment aimed

specifically at their ADHD symptoms, as well as having both impairments

recognized by parents and teachers.

DCD: Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (or Dyspraxia) describes

the motor co-ordination problems and clumsiness typical in AS. Such

difficulties may benefit from intervention from an Occupational Therapist or

Physiotherapist.

Tics and Tourette’s syndrome: Several reports have documented the

co-occurrence of tics in Asperger’s Syndrome. Tourette’s syndrome has also been

observed in children with autism. Tics may be verbal or motor.

Feeding and Eating Problems: Problems with food including food

refusal, selective eating, hoarding, pica and overeating have all been observed

among children with an ASD. Some children have difficulties coping with mixed

textures, may eat their food in a certain order and may even ask for their food

on different plates.

ASSESSMENT

A general assessment should cover the following areas:

· The child’s developmental history.

· Observations of the child in structured and semi-structured situations.

· Nursery/School report.

· Assessment of cognitive level.

· Assessment of problem behaviours.

· Speech and language assessment.

· Audiology and visual tests if indicated. Chromosomal screen is needed if there are dysmorphic (abnormal) features.

Physical investigations may be specifically indicated in some cases including

the need for an EEG, or screening for Fragile X and other chromosomal

abnormalities. It is still debatable as to whether these investigations are

worth performing routinely as the yield of positive results is relatively low.

Diagnostic Interviews: A number of interviews exist that help

clarify the diagnosis and are also used in research. These include the Autism

Diagnostic Interview, the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication

Disorders, the Childhood Autism Rating Scale and a new computerised

interview, the Developmental, Dimensional and Diagnostic Interview (3Di).

3.5 Documentation of assessment, interpretation and report writing

Documentation is an essential element of reflective practice. It makes children’s play and learning experiences visible…to children, parents and teachers. It is a way to visibly demonstrate the competence of the child.

Documentation simply means keeping a record of what is observed while students are engaged in a learning experience while playing and exploring. Records might include teacher observations which focus on specific skills, concepts, or characteristics outlined in the kindergarten curriculum. Daily observations may be both planned and spontaneous to ensure that all learning experiences that may emerge from a particular activity are included.

There are various forms of documenting a student’s learning experiences. It might include the use of student’s artwork and writing, photographs, videotapes and/or tape-recordings. Documentation can be as simple as an attractive display of children’s work on a wall or it can be a more elaborately crafted display board that tells the story of an experience of a child or a group of children. Various types of documentation may include display boards, scrap books, photo albums, web sites (accessible only to parents), and emails to parents, bulletin board displays and newsletters to parents. All types of documentation should include a title, photos or sketches of children’s work with written captions, children’s illustrations of the experience and additional written descriptions of the learning.

Documentation pulls it all together for the students, teachers, and the parents. It provides students with the opportunity to revisit their work which, in turn, provides teachers with the opportunity to discuss with them their interests, their ideas and their plans. By becoming involved in the documentation of their own learning experiences, students become more reflective and more engaged in the learning that is happening all around them.

Report Writing

Many different professionals may provide input in the assessment of a child with a suspected disability. When this occurs, a comprehensive report based on the findings must be written.

The purpose of this report is to communicate results in such a way that the reader will understand the rationale behind the recommendations, and will be able to use the recommendations as practical guidelines for intervention.

This report may be presented to the parent, sent to an outside doctor or agency, or presented to the Eligibility Committee. In any case, the report needs to be professional, comprehensive, and practical.

Writing a good report is a real skill. The fact is, all the wonderful data collection becomes useless if it cannot be interpreted and explained in a clear and concise manner. For example, being too general or explaining results poorly creates many problems and confusion for readers. Also, citing numerous general recommendations will not be practical for the school, teacher, or parents.

Writing a report that contains jargon that no one other than you understands is also useless. Completing an extremely lengthy report in an attempt to be too comprehensive will result only in losing your reader.