INTRODUCTION

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the name given to a group of inherited eye diseases that affect the retina (the light-sensitive part of the eye). RP causes the breakdown of photoreceptor cells (cells in the retina that detect light). Photoreceptor cells capture and process light helping us to see. As these cells breakdown and die, patients experience progressive vision loss.

The most common feature of all forms of RP is a gradual breakdown of rods (retinal cells that detect dim light) and cones (retinal cells that detect light and color). Most forms of RP first cause the breakdown of rod cells. These forms of RP, sometimes called rod-cone dystrophy, usually begin with night blindness. Night blindness is somewhat like the experience normally sighted individuals encounter when entering a dark movie theatre on a bright, sunny day. However, patients with RP cannot adjust well to dark and dimly lit environments.

HEREDITY AND RETINITIS PIGMENTOSA

To understand how RP is inherited, it's important to know a little more about genes and how they are passed from parent to child. Genes are bundled together on structures called chromosomes. Each cell in your body contains 23 pairs of chromosomes. One copy of each chromosome is passed by a parent at conception through egg and sperm cells. The X and Y chromosomes, known as sex chromosomes, determine whether a person is born female (XX) or male (XY). The 22 other paired chromosomes, called autosomes, contain the vast majority of genes that determine non-sex traits. RP can be inherited in one of three ways:

Autosomal recessive inheritance

In autosomal recessive inheritance, it takes two copies of the mutant gene to give rise to the disorder. An individual with a recessive gene mutation is known as a carrier. When two carriers have a child, there is a:

- 1 in 4 chance the child will have the disorder

- 1 in 2 chance the child will be a carrier

- 1 in 4 chance the child will neither have the disorder nor be a carrier

Autosomal dominant inheritance

In this inheritance pattern, it takes just one copy of the gene with a disorder-causing mutation to bring about the disorder. When a parent has a dominant gene mutation, there is a 1 in 2 chance that any children will inherit this mutation and the disorder.

X-linked inheritance

In this form of inheritance, mothers carry the mutated gene on one of their X chromosomes and pass it to their sons. Because females have two X chromosomes, the effect of a mutation on one X chromosome is offset by the normal gene on the other X chromosome. If a mother is a carrier of an X-linked disorder there is a:

- 1 in 2 chance of having a son with the disorder

- 1 in 2 chance of having a daughter who is a carrier

SYMPTOMS

As the disease progresses and more rod cells breakdown, patients lose their peripheral vision (tunnel vision). Individuals with RP often experience a ring of vision loss in their periphery, but retain clear central vision. Others report the sensation of tunnel vision, as though they see the world through a straw. Many patients with retinitis pigmentosa retain a small degree of central vision throughout their life.

Other forms of RP, sometimes called cone-rod dystrophy, first affect central vision. Patients first experience a loss of central vision that cannot be corrected with glasses or contact lenses. With the loss of cone cells also comes disturbances in color perception. As the disease progresses, rod cells degenerate causing night blindness and peripheral vision.

Symptoms of RP are most often recognized in children, adolescents and young adults, with progression of the disease continuing throughout the individual's life. The pattern and degree of visual loss are variable.

CAUSES

Retinitis pigmentosa is an inherited disorder, and therefore not caused by injury, infection or any other external or environmental factors. People suffering from RP are born with the disorder already programmed into their cells. Doctors can see the first signs of retinitis pigmentosa in affected children as early as age 10. Research suggests that several different types of gene mutations (changes in genes) can send faulty messages to the retinal cells which leads to their progressive degeneration. In most cases, the disorder is linked to a recessive gene, a gene that must be inherited from both parents in order to cause the disease. But dominant genes and genes on the X chromosome also have been linked to retinitis pigmentosa. In these cases, only one parent has passed the disease gene. In some cases, a new mutation causes the disease to occur in a person who does not have a family history of the disease. The disorder also can show up as part of other syndromes, such as Bassen-Kornzweig disease or Kearns-Sayre syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS

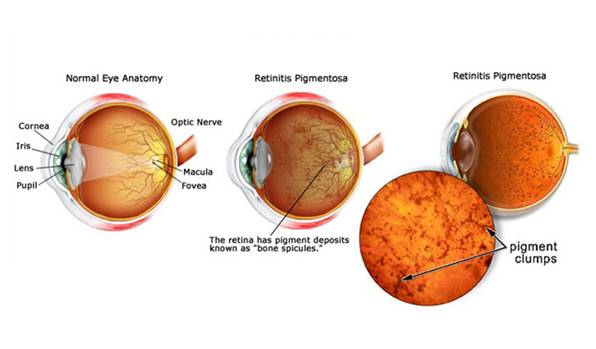

RP is diagnosed in part through an examination of the retina. An eye care professional will use an ophthalmoscope, a tool that allows for a wider, clear view of the retina. This typically reveals abnormal, dark pigment deposits that streak the retina. These pigment deposits are in part why the disorder was named retinitis pigmentosa. Other tests for RP include:

- Electroretinogram (ERG). An ERG measures the electrical activity of photoreceptor cells. This test uses gold foil or a contact lens with electrodes attached. A flash of light is sent to the retina and the electrodes measure rod and cone cell responses. People with RP have a decreased electrical activity, reflecting the declining function of photoreceptors.

- Visual field testing. To determine the extent of vision loss, a clinician will give a visual field test. The person watches as a dot of light moves around the half-circle (180 degrees) of space directly in front of the head and to either side. The patient pushes a button to indicate that he or she can see the light. This process results in a map of their visual field and their central vision.

- Genetic testing. In some cases, a clinician takes a DNA sample from the person to give a genetic diagnosis. In this way a person can learn about the progression of their particular form of the disorder.

TREATMENT

There is no known cure for retinitis pigmentosa. However, there are few treatment options such as light avoidance and/or the use of low-vision aids to slow down the progression of RP. Some practitioners also consider vitamin A as a possible treatment option to slow down the progression of RP. Research suggests taking high doses of vitamin A (15,000 IU/day) may slow progression a little in some people, but the results are not strong. Taking too much vitamin A can be toxic and the effects of vitamin A on the disease is relatively weak. More research must be conducted before this is a widely accepted form of therapy.

Research is also being conducted in areas such as gene therapy research, transplant research, and retinal prosthesis. Since RP is usually the result of a defective gene, gene therapy has become a widely explored area for future research. The goal of such research would be to discover ways healthy genes can be inserted into the retina. Attempts at transplanting healthy retinal cells into sick retinas are being made experimentally and have not yet been considered as clinically safe and successful. Retinal prosthesis is also an important area of exploration because the prosthesis, a man-made device intended to replace a damaged body part, can be designed to take over the function of the lost photoreceptors by electrically stimulating the remaining healthy cells of the retina.Through electrical stimulation, the activated ganglion cells can provide a visual signal to the brain. The visual scene captured by a camera is transmitted via electromagnetic radiation to a small decoder chip located on the retinal surface. Data and power are then sent to a set of electrodes connected to the decoder. Electrical current passing from individual electrodes stimulate cells in the appropriate areas of the retina corresponding to the features in the visual scene.