INTRODUCTION TO STRUCTURALISM AND FUNCTIONALISM

The goal of the first psychologists was to determine the structure of consciousness just as chemists had found the structure of chemicals. Thus, the school of psychology associated with this approach earned the name structuralism. This perspective began in Germany in the laboratory of Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920).

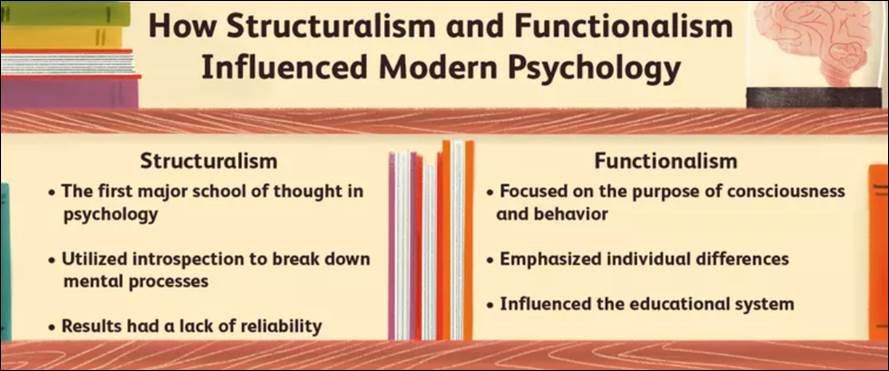

Before long, however, psychologists suggested that psychology should not concern itself with the structure of consciousness because, they argued, consciousness was always changing so it had no basic structure. Instead, they suggested that psychology should focus on the function or purpose of consciousness and how it leads to adaptive behavior. This approach to psychology was consistent with Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which exerted a significant impact on the character of psychology. The school of functionalism developed and flourished in the United States, which quickly surpassed Germany as the primary location of scientific psychology.

Structuralism, in psychology, a systematic movement founded in Germany by Wilhelm Wundt and mainly identified with Edward B. Titchener. Structuralism sought to analyze the adult mind (defined as the sum total of experience from birth to the present) in terms of the simplest definable components and then to find the way in which these components fit together in complex forms.

Introspection: Structuralism's Main Tool

Titchener took Wundt's experimental technique, known as introspection, and used it to focus on the structures of the human mind. Anything that could not be investigated using this technique, Titchener believed, was not in the domain of psychology.

Titchener believed that the use of introspection, which utilized observers who had been rigorously trained to analyze their feelings and sensations when shown a simple stimulus, could be used to discover the structures of the mind. He spent the bulk of his career devoted to this task.

Although structuralism represented the emergence of psychology as a field separate from philosophy, the structural school lost considerable influence when Titchener died. The movement led, however, to the development of several countermovements that tended to react strongly to European trends in the field of experimental psychology. Behaviour and personality were beyond the scope considered by structuralism. In separating meaning from the facts of experience, structuralism opposed the phenomenological tradition of Franz Brentano’s act psychology and Gestalt psychology, as well as the functionalist school and John B. Watson’s behaviourism. Serving as a catalyst to functionalism, structuralism was always a minority school of psychology in America.

Structuralism was the first school of psychology and focused on breaking down mental processes into the most basic components. Researchers tried to understand the basic elements of consciousness using a method known as introspection.

Wilhelm Wundt, the founder of the first experimental psychology lab, is often associated with this school of thought. However, Wundt referred to his view of psychology as voluntarism. It was his student, Edward B. Titchener, who coined the term structuralism. Wundt's theories tended to be much more holistic than the ideas that Titchener later introduced in the United States.

While Wundt's work helped to establish psychology as a separate science and contributed methods to experimental psychology, Titchener's development of structuralism helped establish the very first "school" of psychology. Structuralism itself did not last long beyond Titchener's death.

Strengths and Criticisms of Structuralism

By today’s scientific standards, the experimental methods used to study the structures of the mind were too subjective—the use of introspection led to a lack of reliability in results. Other critics argue that structuralism was too concerned with internal behavior, which is not directly observable and cannot be accurately measured.

However, these critiques do not mean that structuralism lacked significance. Structuralism is important because it is the first major school of thought in psychology. The structuralist school also influenced the development of experimental psychology.

Criticisms

Structuralism has faced a large amount of criticism, particularly from the behaviorist school of psychology. The main critique of structuralism was its focus on introspection as the method by which to gain an understanding of conscious experience. Critics argue that self-analysis was not feasible, since introspective students cannot appreciate the processes or mechanisms of their own mental processes. Introspection, therefore, yielded different results depending on who was using it and what they were seeking. Some critics also pointed out that introspective techniques actually resulted in retrospection – the memory of a sensation rather than the sensation itself.

Behaviorists fully rejected even the idea of the conscious experience as a worthy topic in psychology, since they believed that the subject matter of scientific psychology should be strictly operationalized in an objective and measurable way. Because the notion of a mind could not be objectively measured, it was not worth further inquiry. Structuralism also believes that the mind could be dissected into its individual parts, which then formed conscious experience. This also received criticism from the Gestalt school of psychology, which argues that the mind cannot be broken down into individual elements.

Besides theoretical attacks, structuralism was criticized for excluding and ignoring important developments happening outside of structuralism. For instance, structuralism did not concern itself with the study of animal behavior, abnormal behavior, and personality. In addition, structuralism denied adopting the theory of evolution into its theory, which is arguably its biggest downfall. Ironically, in a critique of functional psychology, Titchener writes in his Systematic Psychology:

“[Functional psychology] was born of the enthusiasm of the post-Darwinian days, when evolution seemed to answer all the riddles of the universe; it has been nourished on analogies drawn from a loose and popular biology; it will pass as other fashions pass.”

Titchener himself was criticized for not using his psychology to help answer practical problems. Instead, Titchener was interested in seeking pure knowledge that to him was more important that commonplace issues.

Functionalism, in psychology, a broad school of thought originating in the U.S. during the late 19th century that attempted to counter the German school of structuralism led by Edward B. Titchener. Functionalists, including psychologists William James and James Rowland Angell, and philosophers George H. Mead, Archibald L. Moore, and John Dewey, stressed the importance of empirical, rational thought over an experimental, trial-and-error philosophy. The group was concerned more with the capability of the mind than with the process of thought. The movement was thus interested primarily in the practical applications of research.

The union between theory and application reached its zenith with John Dewey’s development of a laboratory school at the University of Chicago in 1896 and the publication of his keystone article, “The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology” (1896), which attacked the philosophy of atomism and the concept of elementarism, including the behavioral theory of stimulus and response. The work of John Dewey and his associates stimulated the progressive-school movement, which attempted to apply functionalist principles to education. In the early and mid-20th century, an offshoot theory emerged: the transactional theory of perception, the central thesis of which is that learning is the key to perceiving.

The early functionalists included the pre-eminent psychologist and philosopher William James. James promoted the idea that the mind and consciousness itself would not exist if it did not serve some practical, adaptive purpose. It had evolved because it presented advantages. Along with this idea, James maintained that psychology should be practical and should be developed to make a difference in people's lives.

One of the difficulties that concerned the functionalists was how to reconcile the objective, scientific nature of psychology with its focus on consciousness, which by its nature is not directly observable. Although psychologists like William James accepted the reality of consciousness and the role of the will in people's lives, even he was unable to resolve the issue of scientific acceptance of consciousness and will within functionalism.

Other functionalists, like John Dewey, developed ideas that moved ever farther from the realm that structuralism had created. Dewey, for example, used James's ideas as the basis for his writings, but asserted that consciousness and the will were not relevant concepts for scientific psychology. Instead, the behavior is the critical issue and should be considered in the context in which it occurs. For example, a stimulus might be important in one circumstance, but irrelevant in another. A person's response to that stimulus depends on the value of that stimulus in the current situation. Thus, practical and adaptive responses characterize behavior, not some unseen force like consciousness.

This dilemma of how to deal with a phenomenon as subjective as consciousness within the context of an objective psychology ultimately led to the abandonment of functionalism in favor of behaviorism, which rejected everything dealing with consciousness. By 1912, very few psychologists regarded psychology as the study of mental content—the focus was on behavior instead. As it turned out, the school of functionalism provided a temporary framework for the replacement of structuralism, but was itself supplanted by the school of behaviorism.

Interestingly, functionalism drew criticism from both the structuralists and from the behaviorists. The structuralists accused the functionalists of failing to define the concepts that were important to functionalism. Further, the structuralists declared that the functionalists were simply not studying psychology at all; psychology to a structuralist involved mental content and nothing else. Finally, the functionalists drew criticism for applying psychology; the structuralists opposed applications in the name of psychology.

On the other hand, behaviorists were uncomfortable with the functionalists' acceptance of consciousness and sought to make psychology the study of behavior. Eventually, the behavioral approach gained ascendance and reigned for the next half century.

Functionalism was important in the development of psychology because it broadened the scope of psychological research and application. Because of the wider perspective, psychologists accepted the validity of research with animals, with children, and with people having psychiatric disabilities. Further, functionalists introduced a wide variety of research techniques that were beyond the boundaries of structural psychology, like physiological measures, mental tests, and questionnaires. The functionalist legacy endures in psychology today.

Some historians have suggested that functional psychology was consistent with the progressivism that characterized American psychology at the end of the nineteenth century: more people were moving to and living in urban areas, science seemed to hold all the answers for creating a Utopian society, educational reform was underway, and many societal changes faced America. It is not surprising that psychologists began to consider the role that psychology could play in developing a better society.

Although functionalism has never become a formal, prescriptive school, it has served as a historic link in the philosophical evolution linking the structuralist’s concern with the anatomy of the mind to the concentration on the functions of the mind and, later, to the development and growth of behaviourism.