Unit I: Screening, Diagnosis & Assessment

1. Screening, diagnosis & assessment: concept and definition

2. Screening tools: M-CHAT, Screening Test for Autism

3. Diagnostic criteria: DSM-IV, DSM-V, ICD-10

4. Diagnostic tools: CARS, CARS II, Autism Behavior Checklist, ADOS, Asperger’s Syndrome Diagnostic Scale, RAADS; Indian Tools and Cultural Adaptations

5. Differential Diagnosis

1. Screening, diagnosis & assessment: concept and definition

The purpose of screening is to determine whether a woman needs assessment. The purpose of assessment is to gather the detailed information needed for a treatment plan that meets the individual needs of the woman. Many standardized instruments and interview protocols are available to help counsellors perform appropriate screening and assessment for women.

Screening involves asking questions carefully designed to determine whether a more thorough evaluation for a particular problem or disorder is warranted. Many screening instruments require little or no special training to administer. Screening differs from assessment in the following ways:

· Screening is a process for evaluating the possible presence of a particular problem. The outcome is normally a simple yes or no.

· Assessment is a process for defining the nature of that problem, determining a diagnosis, and developing specific treatment recommendations for addressing the problem or diagnosis.

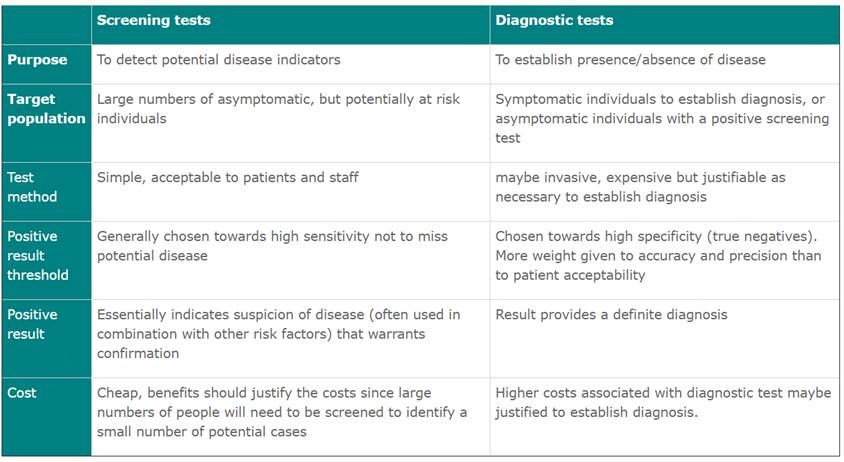

Screening tests are not diagnostic tests

The primary purpose of screening tests is to detect early disease or risk factors for disease in large numbers of apparently healthy individuals.

The purpose of a diagnostic test is to establish the presence (or absence) of disease as a basis for treatment decisions in symptomatic or screen positive individuals (confirmatory test). Some of the key differences are tabled below:

2. Screening tools: M-CHAT, Screening Test for Autism

ASD screening is the first step in diagnosing the disorder. While there is no cure for ASD, early treatment can help reduce autism symptoms and improve quality of life.

The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised (M-CHAT-R) is a screener that will ask a series of 20 questions about your child’s behavior. It's intended for toddlers between 16 and 30 months of age.

Instructions for Use

The M-CHAT-R can be administered and scored as part of a well-child care visit, and also can be used by specialists or other professionals to assess risk for ASD. The primary goal of the M-CHAT-R is to maximize sensitivity, meaning to detect as many cases of ASD as possible. Therefore, there is a high false positive rate, meaning that not all children who score at risk will be diagnosed with ASD. To address this, we have developed the Follow-Up questions (M-CHAT-R/F). Users should be aware that even with the Follow-Up, a significant number of the children who screen positive on the M-CHAT-R will not be diagnosed with ASD; however, these children are at high risk for other developmental disorders or delays, and therefore, evaluation is warranted for any child who screens positive. The M-CHAT-R can be scored in less than two minutes.

Scoring Algorithm

For all items except 2, 5, and 12, the response “NO” indicates ASD risk; for items 2, 5, and 12, “YES” indicates ASD risk. The following algorithm maximizes psychometric properties of the M-CHAT-R:

LOW-RISK: Total Score is 0-2; if child is younger than 24 months, screen again after second birthday. No further action required unless surveillance indicates risk for ASD.

MEDIUM-RISK: Total Score is 3-7; Administer the Follow-Up (second stage of M-CHAT-R/F) to get additional information about at-risk responses. If M-CHAT-R/F score remains at 2 or higher, the child has screened positive. Action required: refer child for diagnostic evaluation and eligibility evaluation for early intervention. If score on Follow-Up is 0-1, child has screened negative. No further action required unless surveillance indicates risk for ASD. Child should be rescreened at future well-child visits.

HIGH-RISK: Total Score is 8-20; It is acceptable to bypass the Follow-Up and refer immediately for diagnostic evaluation and eligibility evaluation for early intervention.

The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) is a psychological questionnaire that evaluates risk for autism spectrum disorder in children ages 16–30 months. The 20-question test is filled out by the parent, and a follow-up portion is available for children who are classified as medium- to high-risk for autism spectrum disorder. Children who score in the medium to high-risk zone may not necessarily meet criteria for a diagnosis. The checklist is designed so that primary care physicians can interpret it immediately and easily. The M-CHAT has shown fairly good reliability and validity in assessing child autism symptoms in recent studies.

Limitations

The M-CHAT suffers from the same problems as other self-report inventories, in that scores can be easily exaggerated or minimized by the person completing them. Like all questionnaires, the way the instrument is administered can have an effect on the final score. If a patient is asked to fill out the form in front of other people in a clinical environment, for instance, social expectations have been shown to elicit a different response compared to administration via a postal survey.

The M-CHAT is a screener for potential symptoms for autism spectrum disorder in children, and cannot be administered as a diagnostic tool. Many pediatricians have been found to underdetect cognitive and emotional/behavioral disorders in children. This underdetection is due to failure to use standardized test, reliance on clinical impressions, the restricted sample of behavior obtained, and the atypical behavior of children in a doctor's office.

Factors such as socioeconomic status and parent education level have been found to impact the generalizability of both the M-CHAT and the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT) as a reliable and valid screener for children of all backgrounds.

Developmental Screening

Developmental screening takes a closer look at how your child is developing. Your child will get a brief test, or you will complete a questionnaire about your child. The tools used for developmental and behavioral screening are formal questionnaires or checklists based on research that ask questions about a child’s development, including language, movement, thinking, behavior, and emotions. Developmental screening can be done by a doctor or nurse, but also by other professionals in healthcare, community, or school settings.

Developmental screening is more formal than developmental monitoring and normally done less often than developmental monitoring. Your child should be screened if you or your doctor have a concern. However, developmental screening is a regular part of some of the well-child visits for all children even if there is not a known concern.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends developmental and behavioral screening for all children during regular well-child visits at these ages:

- 9 months

- 18 months

- 30 months

In addition, AAP recommends that all children be screened specifically for ASD during regular well-child doctor visits at:

- 18 months

- 24 months

- Additional screening might be needed if a child is at high risk for ASD (e.g., having a sister, brother or other family member with an ASD) or if behaviors sometimes associated with ASD are present.

If your child is at higher risk for developmental problems due to preterm birth, low birthweight, environmental risks like lead exposure, or other factors, your healthcare provider may also discuss additional screening. If a child has an existing long-lasting health problem or a diagnosed condition, the child should have developmental monitoring and screening in all areas of development, just like those without special healthcare needs.

If your child’s healthcare provider does not periodically check your child with a developmental screening test, you can ask that it be done.

There are many different developmental screening tools. No single tool can diagnose autism. Rather, a combination of many tools is necessary for an autism diagnosis.

Some examples of screening tools include:

- Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ)

- Autism Diagnostic Interview — Revised (ADI-R)

- Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS)

- Autism Spectrum Rating Scales (ASRS)

- Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS)

- Pervasive Developmental Disorders Screening Test — Stage 3

- Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS)

- Gilliam Autism Rating Scale

- Screening Tool for Autism in Toddlers and Young Children (STAT)

- Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ)

According to the CDC Trusted Source, the new edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) also offers standardized criteria to help diagnose ASD.

3. Diagnostic criteria: DSM-IV, DSM-V, ICD-10

DSM-IV – Diagnostic Classifications

Pervasive Development Disorders (PDD)

The term “PDD” is widely used by professionals to refer to children with autism and related disorders; however, there is a great deal of disagreement and confusion among professionals concerning the PDD label. Diagnosis of PDD, including autism or any other developmental disability, is based upon the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), published by the American Psychiatric Association (Washington, DC, 1994), and is the main diagnostic reference of mental health professionals in the U.S.

According to the DSM-IV, the term “PDD” is not a specific diagnosis, but an umbrella term under which the specific diagnoses are defined.

Diagnostic labels are used to indicate commonalities among individuals. The key defining symptom of autism that differentiates it from other syndromes and/or conditions is substantial impairment in social interaction (Frith, 1989). The diagnosis of autism indicates that qualitative impairments in communication, social skills, and range of interests and activities exist. As no medical tests can be performed to indicate the presence of autism or any other PDD, the diagnosis is based upon the presence or absence of specific behaviors. For example, a child may be diagnosed as having PDD-NOS if he or she has some behaviors that are seen in autism, but does not meet the full criteria for having autism. Most importantly, whether a child is diagnosed with a PDD (like autism) or a PDD-NOS, his/her treatment will be similar.

Autism is a spectrum disorder, with symptoms ranging from mild to severe. As a spectrum disorder, the level of developmental delay is unique to each individual. If a diagnosis of PDD-NOS is made, rather than autism, the diagnosticians should clearly specify the behaviors present. Evaluation reports are more useful if they are specific and become more helpful for parents and professionals in later years when reevaluations are conducted.

Ideally, a multidisciplinary team of professionals should evaluate a child suspected of having autism. The team may include, but may not be limited to, a psychologist or psychiatrist, a speech pathologist and other medical professionals, including a developmental pediatrician and/or neurologist. Parents and teachers should also be included, as they have important information to share when determining a child’s diagnosis.

In the end, parents should be more concerned that their child find the appropriate educational treatment based on their needs, rather than spending too much effort to find the perfect diagnostic label. Most often, programs designed specifically for children with autism will produce greater benefits, while the use of the general PDD label can prevent children from obtaining services relative to their needs.

Also within each diagnosis is the Autism Society’s Panel of Professional Advisors’ recommended definition of the autism spectrum and related syndromes and conditions, which is not to be used for research purposes but rather for defining the demographics of the Autism Society’s membership. The Autism Society is not attempting to represent individuals with related syndromes or conditions who do not also have autism, but rather those where autism is present in related syndromes and conditions, and where autism is the defining syndrome (e.g., autism-Asperger’s). The rationale for this position is due to the unique service needs that are imperative for individuals with autism that may not be required of the cohort disability.

· Autistic Disorder (299.00 DSM-IV)

· Asperger’s Disorder (299.80 DSM-IV)

· Rett’s Disorder (299.80 DSM-IV)

· Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (299.10 DSM-IV)

· PDD-NOS (299.80 DSM-IV)

Autistic Disorder (299.00 DSM-IV)

The central features of Autistic Disorder are the presence of markedly abnormal or impaired development in social interaction and communication, and a markedly restricted repertoire of activity and interest. The manifestations of this disorder vary greatly depending on the developmental level and chronological age of the individual. Autistic Disorder is sometimes referred to as Early Infantile Autism, Childhood Autism, or Kanner’s Autism (page 66).

1. A total of six (or more) items from (1), (2), and (3), with at least two from (1), and one each from (2) and (3):

2. Qualitative impairment in social interaction, as manifested by at least two of the following:

3. Marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors such as eye to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction .

o Failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level

o A lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people (e.g., by a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest)

o Lack of social or emotional reciprocity

4. Qualitative impairments in communication as manifested by at least one of the following:

5. Delay in, or total lack of, the development of spoken language (not accompanied by an attempt to compensate through alternative modes of communication such as gestures or mime)

o In individuals with adequate speech, marked impairment in the ability to initiate or sustain a conversation with others

o Stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language

o Lack of varied, spontaneous make-believe play or social imitative play appropriate to developmental level

6. Restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, as manifested by at least one of the following:

o Encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus

o Apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional routines or rituals

o Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand or finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements)

o Persistent preoccupation with parts of object

7. Delays or abnormal functioning in at least one of the following areas, with onset prior to age 3 years:

o Social interaction

o Language as used in social communication

o Symbolic or imaginative play

8. The disturbance is not better accounted for by Rett’s Disorder or Childhood Disintegrative Disorder.

Asperger’s Disorder (299.80 DSM-IV)

The essential features of Asperger’s Disorder are severe and sustained impairment in social interaction and the development of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interest, and activity. The disturbance must clinically show significant impairment in social, occupational, and other important areas of functioning. In contrast to Autistic Disorder, there are no clinically significant delays in language. In addition there are no clinically significant delays in cognitive development or in the development of age-appropriate self-help skills, adaptive behavior, and curiosity about the environment in childhood.

1. Qualitative impairment in social interaction, as manifested by at least two of the following:

o Marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal behaviors such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction

o Failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to developmental level

o A lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people (e.g., by a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest to other people)

o Lack of social or emotional reciprocity

2. Restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, as manifested by at least one of the following:

o Encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in intensity or focus

o Apparently inflexible adherence to specific, non-functional routines or rituals

o Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand or finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements)

o Persistent preoccupation with parts of objects

3. The disturbance causes clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

4. There is no clinically significant general delay in language (e.g., single words used by age 2 years, communicative phrases used by age 3 years)

5. There is no clinically significant delay in cognitive development or in the development of age-appropriate self-help skills, adaptive behavior (other than in social interaction), and curiosity about the environment in childhood.

6. Criteria are not met for another specific Pervasive Developmental Disorder or Schizophrenia.

Rett’s Disorder (299.80 DSM-IV)

The essential feature of Rett’s Disorder is the development of multiple specific deficits following a period of normal functioning after birth. There is a loss of previously acquired purposeful hand skills before subsequent development of characteristic hand movement resembling hand wringing or hand washing. Interest in the social environment diminishes in the first few years after the onset of the disorder. There is also significant impairment in expressive and receptive language development with severe psychomotor retardation. (Page 71)

1. All of the following:

o Apparently normal prenatal and prenatal development

o Apparently normal psychomotor development through the first 5 months after birth

o Normal head circumference at birth

2. Onset of all of the following after the period of normal development:

o Deceleration of head growth between ages 5 and 48 months

o Loss of previously acquired purposeful hand skills between ages 5 and 30 months with the subsequent development of stereotyped hand movements (e.g., hand-wringing or hand washing)

o Loss of social engagement early in the course (although often social interaction develops later)

o Appearance of poorly coordinated gait or trunk movements

o Severely impaired expressive and receptive language development with severe psychomotor retardation

Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (299.10 DSM-IV)

The central feature of Childhood Disintegrative Disorder is a marked regression in multiple areas of functioning following a period of at least two years of apparently normal development. After the first two years of life, the child has a clinically significant loss of previously acquired skills in at least two of the following areas: expressive or receptive language; social skills or adaptive behavior; bowel or bladder control; or play or motor skills. Individuals with this disorder exhibit the social and communicative deficits and behavioral features generally observed in Autistic Disorder, as there is qualitative impairment in social interaction, communication, and restrictive, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. (Page 73)

1. Apparently normal development for at least the first 2 years after birth as manifested by the presence of age-appropriate verbal and nonverbal communication, social relationships, play, and adaptive behavior.

2. Clinically significant loss of previously acquired skills (before age 10 years) in at least two of the following areas:

o Expressive or receptive language

o Social skills or adaptive behavior

o Bowel or bladder control

o Play

o Motor skills

3. Abnormalities of functioning in at least two of the following areas:

o Qualitative impairment in social interaction (e.g., impairment in nonverbal behaviors, failure to develop peer relationships, lack of social or emotional reciprocity)

o Qualitative impairments in communication (e.g., delay or lack of spoken language, inability to initiate or sustain a conversation, stereotyped and repetitive use of language, lack of varied make-believe play)

o Restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, including motor stereotypes and mannerisms

4. The disturbance is not better accounted for by another specific Pervasive Developmental Disorder or by Schizophrenia.

PDD-NOS (299.80 DSM-IV)

The essential features of PDD-NOS are severe and pervasive impairment in the development of reciprocal social interaction or verbal and nonverbal communication skills; and stereotyped behaviors, interests, and activities. The criteria for Autistic Disorder are not met because of late age onset; atypical and/or sub- threshold symptomotology are present. (Page 77-78)

This category should be used when there is a severe and pervasive impairment in the development of reciprocal social interaction or verbal and nonverbal communication skills, or when stereotyped behavior, interests, and activities are present, but the criteria are not met for a specific Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Schizophrenia, Schizotypical Personality Disorder, or Avoidant Personality Disorder. For example, this category includes “atypical autism“– presentations that do not meet the criteria for Autistic Disorder because of late age of onset, atypical symptomatology, or sub-threshold symptomatology, or all of these.

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association released the fifth edition of its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

The DSM-5 is now the standard reference that healthcare providers use to diagnose mental and behavioral conditions, including autism.

A. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive, see text):

1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

3. Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

Specify current severity: Severity is based on social communication impairments and restricted repetitive patterns of behavior. (See table below.)

B. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive; see text):

1. Stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech (e.g., simple motor stereotypies, lining up toys or flipping objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

2. Insistence on sameness, inflexible adherence to routines, or ritualized patterns or verbal nonverbal behavior (e.g., extreme distress at small changes, difficulties with transitions, rigid thinking patterns, greeting rituals, need to take same route or eat food every day).

3. Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g, strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects, excessively circumscribed or perseverative interest).

4. Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement).

Specify current severity: Severity is based on social communication impairments and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior. (See table below.)

C. Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities or may be masked by learned strategies in later life).

D. Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of current functioning.

E. These disturbances are not better explained by intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder) or global developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder frequently co-occur; to make comorbid diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability, social communication should be below that expected for general developmental level.

Note: Individuals with a well-established DSM-IV diagnosis of autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified should be given the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Individuals who have marked deficits in social communication, but whose symptoms do not otherwise meet criteria for autism spectrum disorder, should be evaluated for social (pragmatic) communication disorder.

Specify if:

- With or without accompanying intellectual impairment

- With or without accompanying language impairment

- (Coding note: Use additional code to identify the associated medical or genetic condition.)

- Associated with another neurodevelopmental, mental, or behavioral disorder

- (Coding note: Use additional code[s] to identify the associated neurodevelopmental, mental, or behavioral disorder[s].)

- With catatonia

- Associated with a known medical or genetic condition or environmental factor

Table: Severity levels for autism spectrum disorder

|

Severity level |

Social communication |

Restricted, repetitive behaviors |

|

Level 3 |

Severe deficits in verbal and nonverbal social communication skills cause severe impairments in functioning, very limited initiation of social interactions, and minimal response to social overtures from others. For example, a person with few words of intelligible speech who rarely initiates interaction and, when he or she does, makes unusual approaches to meet needs only and responds to only very direct social approaches |

Inflexibility of behavior, extreme difficulty coping with change, or other restricted/repetitive behaviors markedly interfere with functioning in all spheres. Great distress/difficulty changing focus or action. |

|

Level 2 |

Marked deficits in verbal and nonverbal social communication skills; social impairments apparent even with supports in place; limited initiation of social interactions; and reduced or abnormal responses to social overtures from others. For example, a person who speaks simple sentences, whose interaction is limited to narrow special interests, and how has markedly odd nonverbal communication. |

Inflexibility of behavior, difficulty coping with change, or other restricted/repetitive behaviors appear frequently enough to be obvious to the casual observer and interfere with functioning in a variety of contexts. Distress and/or difficulty changing focus or action. |

|

Level 1 |

Without supports in place, deficits in social communication cause noticeable impairments. Difficulty initiating social interactions, and clear examples of atypical or unsuccessful response to social overtures of others. May appear to have decreased interest in social interactions. For example, a person who is able to speak in full sentences and engages in communication but whose to- and-fro conversation with others fails, and whose attempts to make friends are odd and typically unsuccessful. |

Inflexibility of behavior causes significant interference with functioning in one or more contexts. Difficulty switching between activities. Problems of organization and planning hamper inde |

ICD-10 CRITERIA FOR "CHILDHOOD AUTISM"*

A. Abnormal or impaired development is evident before the age of 3 years in at least one of the following areas:

1. receptive or expressive language as used in social communication;

2. the development of selective social attachments or of reciprocal social interaction;

3. functional or symbolic play.

B. A total of at least six symptoms from (1), (2) and (3) must be present, with at least two from (1) and at least one from each of (2) and (3)

1. Qualitative impairment in social interaction are manifest in at least two of the following areas:

a. failure adequately to use eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction;

b. failure to develop (in a manner appropriate to mental age, and despite ample opportunities) peer relationships that involve a mutual sharing of interests, activities and emotions;

c. lack of socio-emotional reciprocity as shown by an impaired or deviant response to other people’s emotions; or lack of modulation of behavior according to social context; or a weak integration of social, emotional, and communicative behaviors;

d. lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment, interests, or achievements with other people (e.g. a lack of showing, bringing, or pointing out to other people objects of interest to the individual).

2. Qualitative abnormalities in communication as manifest in at least one of the following areas:

a. delay in or total lack of, development of spoken language that is not accompanied by an attempt to compensate through the use of gestures or mime as an alternative mode of communication (often preceded by a lack of communicative babbling);

b. relative failure to initiate or sustain conversational interchange (at whatever level of language skill is present), in which there is reciprocal responsiveness to the communications of the other person;

c. stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic use of words or phrases;

d. lack of varied spontaneous make-believe play or (when young) social imitative play

3. Restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities are manifested in at least one of the following:

a. An encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped and restricted patterns of interest that are abnormal in content or focus; or one or more interests that are abnormal in their intensity and circumscribed nature though not in their content or focus;

b. Apparently compulsive adherence to specific, non-functional routines or rituals;

c. Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms that involve either hand or finger flapping or twisting or complex whole body movements;

d. Preoccupations with part-objects of non-functional elements of play materials (such as their oder, the feel of their surface, or the noise or vibration they generate).

C. The clinical picture is not attributable to the other varieties of pervasive developmental disorders; specific development disorder of receptive language (F80.2) with secondary socio-emotional problems, reactive attachment disorder (F94.1) or disinhibited attachment disorder (F94.2); mental retardation (F70-F72) with some associated emotional or behavioral disorders; schizophrenia (F20.-) of unusually early onset; and Rett’s Syndrome (F84.12).

*World Health Organization. (1992). International classification of diseases: Diagnostic criteria for research (10th edition). Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

4. Diagnostic tools: CARS, CARS II, Autism Behavior Checklist, ADOS, Asperger’s Syndrome Diagnostic Scale, RAADS; Indian Tools and Cultural Adaptations

Childhood Autism Rating Scale

The CARS was published in 1988 and aligned with DSM-III criteria. Rellini and associates revealed that there was a 100% agreement between diagnoses made with the CARS and those made by clinicians with ASD expertise who used clinical judgment based on DSM-IV criteria. This measure consists of a 15-item structured interview, with each item scored according to seven levels of severity. The scale was designed for use with children older than 2 years, requires training to administer, and takes about 20 to 30 minutes to complete. It may overidentify very young children or those with severe mental retardation and may underidentify older patients with high-functioning autism. It is still “the strongest, best-documented, and most widely used clinical rating scale for autism.” Of the 30% of practitioners using a tool for the initial evaluation of a child for ASD in the Atlanta study discussed previously, 68% of them used the CARS.

There is a great deal of assessment tools to help in the diagnosis of autism available. One of them is the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS).

CARS was developed by Eric Schopler, Robert Reichier and Barbara Rochen Renner. Just like any other autism assessment tool, it was made to help in the diagnosis of autism in children. The difference CARS have from other behavior rating tools is that it actually can tell the difference if your child has autism or other developmental delay disorders like mental retardation. It makes it easier for healthcare providers, educators and parents to identify and classify children with autism.

How it Works

CARS works by rating your child’s behavior, characteristics, and abilities against the expected developmental growth of a typical child.

As stated in the CARS, these characteristics are evaluated:

- Relationship to people

- Imitation

- Emotional response

- Body use

- Object use

- Adaptation to change

- Visual response

- Listening response

- Taste-smell-touch response and use

- Fear and nervousness

- Verbal communication

- Non-verbal communication

- Activity level

- Level and consistency of intellectual response

- General impressions

It is done by your primary healthcare provider, a teacher or a parent by rating the child’s behaviors from 1 to 4. 1 being normal for your child’s age, 2 for mildly abnormal, 3 for moderately abnormal and 4 as severely abnormal. Scores range form 15 to 60 with 30 being the cutoff rate for a diagnosis of mild autism. Scores 30-37 indicate mild to moderate autism, while scores between 38 and 60 are characterized as severe autism. Keep in mind that while the Childhood Autism Rating Scale can easily be accessed on the internet, using it to evaluate your child on your own is not advised. It is still best to seek professional help in interpreting the result of your child’s CARS.

It should be remembered that constant and keen observation of your child is important when completing the CARS. The parent or teacher or medical provider should be able to have good understanding of the criteria so that accurate results can also be obtained. If any confusion arises, do not hesitate in any way to clear it up with the person in charge of giving you the test. CARS is normally used with children 2 years of age and above. Although CARS has been used in the diagnosis of adolescents as well, according to a study done by the University of Texas Health Science Center.

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale–Second Edition

Schopler E, Van Bourgondien ME, Wellman, GJ, Love SR (2010). Childhood Autism Rating Scale – 2nd Edition. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services

The CARS-2 is an update of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), an older and widely-used rating scale for autism. The original CARS was developed primarily with individuals with comorbid intellectual functioning and was criticized for not accurately identify higher functioning individuals on the autism spectrum. The CARS-2 retained the original CARS form for use with younger or lower functioning individuals (now renamed the CARS2-ST for “Standard Form”), and it developed a separate rating scale for use with higher functioning individuals (named the CARS2-HF for “High Functioning”). Clinically, the original CARS was often misused as a parent questionnaire; it was designed as a clinician rating scale to be completed after a direct observation of the child by a professional familiar with autism who had also obtained some brief training on how to rate the CARS items. The CARS-2 retains this same format. Information from parents can be obtained with the CARS2-QPC (Questionnaire of Parent Concerns), an unscored form for parents to record observations.

CARS2-ST: Children under age 6, or over age 6 but with an estimated IQ of 79 or lower, or a notable communication impairment. CARS-HF: Age 6 or older, with an estimated IQ of 80 or higher and fluent communication.

The Childhood Autism Rating Scale–Second Edition (CARS2) is a 15-item rating scale used to identify children with autism and distinguishing them from those with developmental disabilities. It is empirically validated and provides concise, objective, and quantifiable ratings based on direct behavioral observation. It was normed on a sample of 1,034 individuals with autism spectrum disorders.

This second edition of CARS expands the test’s clinical value, making it more responsive to individuals on the “high functioning” end of autism spectrum disorders. The clinician rates the individual on each item, using a 4-point rating scale. Ratings are based on frequency of the behavior in question, its intensity, peculiarity, and duration.

Physicians, special educators, school psychologists, speech pathologists, and audiologists will all find the CARS-2 easy to give and score.

The CARS-2 includes three forms:

1. Standard Version Rating Booklet (CARS2-ST): Equivalent to the original CARS; for use with individuals younger than 6 years of age and those with communication difficulties or below-average estimated IQs

2. High-Functioning Version Rating Booklet (CARS2-HF): An alternative for assessing verbally fluent individuals, 6 years of age and older, with IQ scores above 80

3. Questionnaire for Parents or Caregivers (CARS2-QPC): An unscored scale that gathers information for use in making CARS2ST and CARS2-HF ratings

The standard and high-functioning forms each include 15 items addressing the following functional areas:

- Relating to People

- Imitation (ST); Social-Emotional Understanding (HF)

- Emotional Response (ST); Emotional Expression and Regulation of Emotions (HF)

- Body Use

- Object Use (ST); Object Use in Play (HF)

- Adaptation to Change (ST); Adaptation to Change/Restricted Interests (HF)

- Visual Response

- Listening Response

- Taste, Smell, and Touch Response and Use

- Fear or Nervousness (ST); Fear or Anxiety (HF)

- Verbal Communication

- Nonverbal Communication

- Activity Level (ST); Thinking/Cognitive Integration Skills (HF)

- Level and Consistency of Intellectual Response

- General Impressions

The parent or caregiver of the individual being assessed completes this unscored form. Its primary purpose is to give the clinician more information on which to base the CARS2-ST or CARS2-HF ratings. The questionnaire covers an individual’s early development; social, emotional, and communication skills; repetitive behaviors; play and routines; and unusual sensory interests.

Autism Behavior Checklist

The Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC) is one component of the Autism Screening Instrument for Educational Planning (ASIEP) and is the only one that has been evaluated psychometrically. The ABC is a 57-item behavior rating scale assessing the behaviors and symptoms of autism for children 3 and older. The instrument consists of a list of 57 questions divided into five categories: (1) sensory, (2) relating, (3) body and object use, (4) language, and (5) social and self-help. Each item has a weighted score ranging from 1 to 4. The ABC is designed to be completed independently by a parent or a teacher familiar with the child for at least 3–6 weeks. It should take from 10 to 20 min to complete. The protocol is then returned to a trained professional for scoring and interpretation.

ADOS

ADOS stands for Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. ADOS is a standardized diagnostic test for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), published by Western Psychological Services (WPS) in 2000 and now available in 15 different languages. Since that time, it has become one of the standard diagnostic tools both school systems and independent clinicians use when screening for developmental disabilities.

ADOS is not required to make a diagnosis of autism. The current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) governs the criteria for making an autism spectrum diagnosis, which any psychologist or psychiatrist can do using whatever methods they find effective.

What ADOS does is provide a systematic and standardized method for identifying kids with ASD. The process involves making direct observations under controlled circumstances that other clinicians are able to replicate. Only trained professionals can administer the ADOS diagnostic screening, but it eliminates some of the differences of opinion otherwise possible when two different experts provide a diagnosis without following common guidelines.

ADOS consists of four different modules. Each of them is designed to provide the most appropriate test for an individual at a certain age or functional level:

- Module One – Designed for individuals who do not have consistent verbal communication skills. Uses entirely non-verbal scenarios for scoring.

- Module Two – Designed for individuals who have minimal verbal communication skills. This may include young children at age-appropriate skill levels; most scenarios require moving around the room and interacting with objects.

- Module Three – Designed for individuals who are verbally fluent and capable of playing with age-appropriate toys. Can be conducted largely at a desk or table.

- Module Four – Designed for individuals who are verbally fluent but beyond the age of playing with toys. Incorporates some Module Three elements but also more conversational aspects regarding daily living experiences.

Each module consists of a set of standardized scenarios that the tester walks the subject through. For example, the presenter lays out a picture that provides a template for your child to place blocks on. The child is intentionally not provided enough blocks to fully complete the task, but the tester shows that they have more. How your child handles the dilemma is observed and evaluated. Do they make a polite request for the extra blocks? Point and scream? Refuse to continue? Each reaction is a scorable behavior for the examiner.

Other components include structured conversations or social scenarios, like a pretend birthday party or snack time. In many of them, minor obstacles are intentionally introduced; things like withholding the blocks, to see how the child copes with it.

The examiner will use a hierarchy of structures called presses to cue responses. In general, the child is expected to show initiative in the early parts of the test, without outside prompting; if this does not occur, the examiner will provide more and more specific tasks to make sure they have a behavior to score.

This can make the test difficult to watch, particularly for parents. You naturally want to provide assistance and make things smoother, but the entire point of the test is to see how the child does without your assistance. Many examiners strongly discourage parents from being in the room when their child is tested, both because of the impulse to help and because parents can present a distraction.

Each module takes around 40 minutes to complete, but, because the modules are oriented at different types of subjects with different behavioral and cognitive issues, not all modules are necessarily used. However, the examiner may choose to use another module after finding that the originally selected one didn’t match the functional abilities of the child closely enough for an accurate score.

Typically, the test will be recorded on video so a team can review it and make the diagnosis. This helps eliminate otherwise subjective biases that are inherent in any individual clinician’s work.

The behaviors of the test subject are given a score of between zero and three, weighed against the normal behavior of a neurotypical person taking the test. Zero indicates a normal behavior while three indicates abnormal function.

The sum of the individual behavior scores is the overall score on the test module. The threshold levels for an ASD diagnosis may vary according to both module and age-level… a 13 on Module 3 might be perfectly normal for an 8-year-old, but indicate low-functioning ASD for a 19-year-old.

It’s common to look for second opinions even after getting an ADOS test score, and it’s important to note that ADOS alone should not be the sole criteria for making a diagnosis—it cannot account for stereotyped behaviors or interests or histories of developmental delays, both key DSM-5 criteria. An ADI-R screening might also be administered as a secondary test to gather more data.

ADOS is constantly being refined and studied to make it more accurate and useful. The test is on its second major revision and further studies are ongoing.

Asperger’s Syndrome Diagnostic Scale

The Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (ASDS) is a quick, easy-to-use rating scale that can help you determine whether a child has Asperger Syndrome.

Anyone who knows the child or youth well can complete this scale. Parents, teachers, siblings, therapists and other professionals can answer the 50 yes/no items in 10 to 15 minutes.

Designed to identify Asperger Syndrome in children aged 5 years to 18 years, this instrument provides an AS Quotient that tells the likelihood that an individual has Asperger Syndrome. The 50 items that comprise the ASDS were drawn from five specific areas of behaviour:

- Cognitive

- Maladaptive

- Language

- Social

- Sensorimotor.

Diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome is difficult because the characteristics of the disorder often resemble those of autism, behaviour disorders, attention deficit hyperactive disorder and learning disabilities.

The ASDS serves an important function by quickly allowing you to determine whether a child or adolescent is likely to have Asperger Syndrome.

All items included in the ASDS represent behaviours that are symptomatic of Asperger Syndrome and all are summed to produce the total score.

The scores from the five subtests present the examiner with information of clinical interest regarding an individual's performance in comparison to that of others with Asperger Syndrome.

The total score has strong diagnostic value in identifying individuals with Asperger Syndrome and is the only score to be used when determining the likelihood of Asperger Syndrome.

This contributes greatly to ease of administration and cuts down on otherwise time-consuming testing procedures.

All items included in the ASDS

represent behaviors that are symptomatic of Asperger Syndrome, and all are

summed to produce the total score. The scores from the five subtests present

the examiner with information of clinical interest regarding an individual¹s

performance in comparison to that of others with Asperger Syndrome. The total

score has strong diagnostic value in identifying individuals with Asperger

Syndrome and is the only score to be used when determining the likelihood of

Asperger Syndrome. This contributes greatly to ease of administration and cuts

down on otherwise time-consuming testing procedures.

The ASDS can be used with confidence to (a) identify persons who have Asperger

Syndrome, (b) document behavioral progress as a consequence of special

intervention programs, (c) target goals for change and intervention on the

student's Individualized Education Program (IEP), and (d) measure Asperger

Syndrome for research purposes. Because the ASDS is based on observations, the

test results are valid only when the rater knows the examinee well; that is,

the examiner has had regular, sustained contact with the examinee for at least

2 weeks.

Raw scores are converted to percentile and standard scores. These scores are

the most important information associated with an individual's ASDS

performance, and analysis of them, augmented by additional test information,

direct information of behavior, and knowledge acquired from other sources, will

result in proper diagnosis of Asperger Syndrome.

RAADS

The Ritvo Autism & Asperger Diagnostic Scale (RAADS) is a psychological self-rating scale developed by the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute, to aid in the identification of patients who may have undiagnosed ASD.

The RAADS was designed to address a major gap in screening services for adults with autism spectrum disorders. With the increased prevalence of the condition and the fact that adults are being referred or self-referred for services or diagnosis with increasing frequency, this instrument is a useful clinical tool to assist clinicians with the diagnosis of this growing population of higher functioning individuals in adulthood.

In adults, self-rating instruments are additionally used. Presumably, the most widely used questionnaires for self-report are the 80-item Ritvo Autism and Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised (RAADS-R) and the 50-item Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ). The AQ was developed to measure the degree to which adults exhibit cognitive traits typical for autism, whereas the RAADS-R was specifically tailored to assist in the diagnosis of adults within the ASD spectrum by addressing symptoms based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) for autistic disorder and Asperger’s disorder, and the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) equivalent. Although a self-rating instrument is a cost-effective tool for limiting assessment of individuals with low likelihood for ASD, these two instruments may be considered too lengthy for screening purposes in the clinical setting. Two shorter versions of the AQ were recently launched, and both showed good discriminating properties between ASD and controls in the general population. However, user-friendly and psychometrically valid screening instruments for adult ASD tested in psychiatric populations are still lacking. The aim of the present study was to construct such a rating scale, based on the RAADS-R, which would reflect the diagnostic criteria for ASD, and to investigate its properties in a wide range of clinically diagnosed psychiatric outpatients with normal intelligence.

There are a few limitations to the RAADS test that make it important to use alongside professional clinical diagnostic processes. Some limitations may include questions being misinterpreted or misunderstood, Unawareness or over reporting of symptoms, and the same symptoms being rated different levels of “obtrusiveness” in daily functioning. Questions of the validity of the test have come up, but studies of over a decade prove it to be promising in the diagnostic process.

Indian Tools and Cultural Adaptations

For diagnosis and measuring severity of autism, an Indian tool was developed in 2009 by the National Institute for Mentally Handicapped. It is called Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISAA). It helps in quantifying the severity of autistic symptoms so as to enable measurement of associated disability. CASI will help in screening for autism.

“For India, with its large population, locally developed instruments must be available to conduct the prevalence studies. Questionnaires developed in other languages and then translated become difficult to use,” the researchers pointed out.

In CASI, spoken Hindi has been used for framing questions and examples added wherever necessary. For instance, ‘does your child look at what you are pointing at, e.g. moon, bird, flower’; ‘does your child play imaginary games like talking on phone, playing with dolls or setting up a toy shop’. For developing the tool, focused group discussions were held with psychiatrists and psychologists, and the tool was pilot tested among children with intellectual disability, children with autism and other developmental disorders, along with typically developing children.

Other experts in the field, however, remain cautious. “While the development of a new tool for screening for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in Hindi is welcome, development of tools in this area should be governed by a new need or to fulfill a gap in existing tools,” says Nandini Chatterjee Singh, UNESCO Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Sustainable Development, New Delhi.

“It is good that the researchers have tried out various steps systematically, but this instrument needs to be tested on a much larger sample before the claims can be verified. A very large part of the instrument has been developed for or 'administered' on specified health care professionals using basically only face validity thus restricting its generalisation,” commented Smita Deshpande, head of the psychiatry department at the RML Hospital, New Delhi.

INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Autism Spectrum Disorder (INDT-ASD) is an indigenously developed tool for the assessment of Indian children with ASD. This tool has been developed by the INCLEN group in India, and it is used by mental health professionals and pediatricians. This work was to demonstrate its clinical utility for speech-language pathologists (SLPs) and sensitize them to this new tool. Forty children between 2 and 10 years of age, with the referral diagnosis of ASD and social communication disorder (SCD) from the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, were enrolled for the study. Diagnosis was reviewed and the Childhood Autism Rating Scale was administered on all children. The children were grouped as (i) children with ASD and (ii) children with SCD, i.e., "no ASD." The INDT-ASD was then administered by an SLP, who was blind to group membership. Thirty-nine out of forty children were correctly diagnosed by the INDT-ASD, showing high diagnostic accuracy of the tool. In addition to this, it is quick to administer, has very elaborate guidelines to observe different behaviors, a good scoring algorithm, and it is freely available in many regional languages. INDT-ASD is a simple and effective tool that can also be used regularly by SLPs and other professionals for the diagnosis of Indian children with ASD.

Tools

AFA has also translated some autism diagnostic and screening tools that are available in regional languages.

The following tools in Bengali and Hindi are provided for free for research use only. These are not clinical diagnostic tools for autism, and should be used only by those who are familiar with the usage of these tools. Commercial use of these tools is strictly prohibited.

Ten Questions (TQ)

The Ten Question (TQ) screen was designed most commonly to measure child disability in developing countries for children 2-9 years. It was designed to be applicable in virtually any cultural setting and includes questions about general functional abilities and developmental milestones rather than culture-specific skills, such as eating with a fork or tying shoelaces.

Primary caregivers of children aged 2-9 answer ten questions that screen the child for impairment or inability in the realms of speech, cognition, hearing, vision, motor/physical, and seizure disorders.

Translations available in Hindi and Bengali

Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ –Child)

The Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) is a questionnaire developed by Professor Simon Baron-Cohen and colleagues at the Autism Research Centre. The Autism Spectrum Quotient—Children’s Version (AQ-Child) is a parent-report questionnaire that aims to assess for autistic traits in 4–11 years old children. The AQ consists of fifty questions assessing 5 different areas: social skill, attention switching, attention to detail, communication and imagination.

Translations available in Hindi and Bengali

Social and Communication Disorders Checklist (SCDC)

The Social Communication Disorder Checklist (SCDC; Skunse, Mandy, Scourfield, 2005) is a 12-item questionnaire that can be completed by parents, that measures social reciprocity and verbal/nonverbal characteristics similar to those found in ASC. The SCDC questions’ content comprises of the domains social reciprocity, nonverbal skills, and pragmatic language usage.

Translations available in Hindi and Bengali

If using these tools for research, please cite the following reference: “Rudra A, Banerjee S, Singhal N, Barua M, Mukerji S, Chakrabarti B (2014): Translation and Usability of Autism Screening and Diagnostic Tools for Autism Spectrum Conditions in India, Autism Research (advanced online publication)”.

Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised (M-CHAT-R)

The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised (M-CHAT-R; Robins, Fein, & Barton, 2009) is a parent-report screening tool to assess risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). It is one of the most rigorously tested screening tools for autism. The M-CHAT-R/F is designed to identify children 16 to 30 months of age who should receive a more thorough assessment for early signs of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or developmental delay. The M-CHAT-R, designed to be administered to parents/guardians, comprises of 20 yes and no questions.

Translations available in Hindi and Bengali

The Hindi version of the M-CHAT-R is provided for free for research use only. It should be used only by those who are familiar with its usage.

5. Differential Diagnosis

As the name implies, Autism Spectrum Disorder is a varied condition, that means, the above clinical features are present on a continuum with very mild impairment at the top end of the scale to more severe impairment of the above functions at the bottom end.

More importantly, there are several clinical conditions, described below, that share some the features of ASD. Hence it is unsurprising that they can mistakenly be labelled as ASD. To complicate things further, many of the below-mentioned conditions can commonly co-occur with ASD. Therefore, as you can appreciate, because of the complexities involved, even the experts can get it wrong.

Moreover, as ASD is a lifelong diagnosis and since a wrong diagnosis can lead to suboptimal or poor outcomes for the child and the family, it becomes imperative to undertake a detailed evaluation to arrive at the diagnosis of ASD, and to rule out the possibility of the below-mentioned conditions that can mimic as ASD.

Therefore, it is crucial to undergo a thorough diagnostic evaluation, and I shall cover this is in my next article.

What does the ‘differential diagnosis’ mean?

Differential diagnosis simply means that there is more than one possibility for a diagnosis. Oxford Dictionary describes ‘differential diagnoses’ (plural noun) as ‘the process of differentiating between two or more conditions which share similar signs or symptoms.’

Following are some of the conditions that can mimic or present as ASD. I have listed them in no particular order. However, conditions in the top half of the list need to be considered more often than the conditions in the bottom half.

1. Learning Disability/Intellectual Disability (LD/ID): Learning disability is the term more commonly used in the UK (and our colleagues in the US, use the term ID or intellectual disability), for any child with significant global developmental delay. Reflecting on my experience, LD/ID must be at the top of my list because of at least two crucial reasons. Firstly, many children with ASD can have a degree of LD, making the need for carrying out a developmental assessment as part of ASD evaluation, vital. Second, it is common to get children with LD confused as having ASD, as children with LD engage in repetitive behaviours for a variety of reasons. Carrying out a developmental assessment will reveal that the language abilities of children with LD are in keeping with their cognitive ability. Moreover, children with LD have better non-verbal communication ability and a reasonable degree of emotional reciprocity, while children with ASD do not.

2. ADHD: It is common for children with ASD to be confused with ADHD. Temper tantrums and repetitive behaviours can be mistaken with hyperactivity. And avoidance of eye contact can be confused with inattention. However, children with ADHD are likely to be impulsive and domineering. They have better abilities for imaginative play and have the intent to communicate their needs. Children with ASD, on the other hand, are likely to be remote, aloof and have impaired intent and ability to communicate their needs. It is crucial to remember that both ASD and ADHD can co-occur.

3. Social Communication Disorder (SCD): It is easy to confuse children with SCD as having ASD because children in both these conditions have impaired verbal and non-verbal communication abilities. However, as DSM-5 manual has specified, unlike children with ASD, SCD children do not have restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviour and activities.

4. Gifted and Talented: Children who are gifted and talented have high intelligence and incredibly good memory. These children, when they have co-existing anxiety, can mimic ASD. Nevertheless, children who are gifted and talented seek social interactions and have good ability to understand and use language appropriate to social context.

5. Anxiety: Anxiety can be a common co-morbidity in children with ASD. Children with a social anxiety disorder or selective mutism can have several features that overlap with ASD. However, unlike children with ASD, these children have good imaginative play skills and are better able to communicate their needs to their parents and carers.

6. Language Disorder: Children with language disorder differ from ASD, in that, they have better motivation and intention to communicate their needs. Their non-verbal communication abilities are not impaired to the same extent as children with ASD. Also, unlike ASD, they have a better imaginative play.

7. Hearing Impairment: It is common for parents of children with ASD, to wonder whether their child is deaf or hearing impaired. This is because, like children with ASD, children with hearing impairment display a lack of response to their name being called, have minimal babbling, and have difficulty in using language to communicate their needs. But unlike ASD, children with hearing impairment can have a good imaginative play, have good eye contact, and can express themselves with a range of gestures, facial expressions, and body language.

8. Attachment Disorder: A history of significant parental deprivation and or neglect in early months and years is an important feature in the history of children with attachment disorder, that is absent in children with ASD. Also, children with attachment disorder develop their social interaction and language abilities when they are placed in a suitable caregiving environment.

9. Regression and Rett’s: The term ‘regression’ is used, when there is a history of a child losing hand skills and or speech and language abilities, they had previously acquired. This can understandably be genuinely concerning to parents. Rett’s syndrome is a clinical condition that occurs specifically in girls, because of a mutation in a specific gene called MECP2. In this condition, girls who appeared to be developing typically, lose speech and their ability to use hands for daily activities. Rett’s syndrome, along with childhood disintegrative disorder, are no longer classed under Autism Spectrum Disorder when DSM was revised, in 2013.

10.Genetic disorders and Syndromic: There are over a dozen syndromes that have overlapping features with ASD. Also, ASD tends to occur more commonly with certain conditions such as Fragile X, Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Down Syndrome, etc. A detailed assessment by a neurodevelopmental paediatrician can identify these conditions.

11.Inherited Metabolic Disorder (IMD): Children with disorders of carbohydrate and protein metabolism could present with a learning disability, hearing impairment, vision impairment, developmental regression, and food intolerance. Presence of an IMD in children with ASD is fortunately rare.

12.Epilepsy: Certain epilepsy such as Landau Kleffner Syndrome (LKS), though rare, can present with the child losing the ability to understand language, display behavioural outbursts and have temper tantrums. An EEG (electroencephalogram/tracing of the brain) can help identify seizures, as the cause of ASD like symptoms.

13.Tourette’s: Children with Tourette’s syndrome and accompanying ADHD symptoms can be misinterpreted to have ASD, because of impaired social interaction skills and social communication skills secondary to sudden utterances, brief but repetitive tics, etc.

14.Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): Both ASD and OCD can have similar symptoms. However, unlike ASD, children with OCD have better social interaction and social communication skills. Also, unlike children with ASD, children with OCD tend to find their symptoms distressing.

15.Sensory Processing Difficulties (SPD): SPD was not part of the diagnostic criteria for ASD until the latest revision to DSM in 2013. Inclusion of SPD as one of the features for the diagnosis of ASD has been helpful, as I encounter some degree of sensory difficulties almost universally in children with ASD. Children with SPD can be either hypersensitive or hyposensitive to a variety of sensations of sound, sight, smell, touch, and movement. Hence, children with SPD can be sensory seeking or extremely avoidant of certain sensations, resulting in some to mistakenly think them as having ASD. SPD is not recognised as a separate clinical disorder in DSM-5.

16.Vision Impairment (VI): Children with vision impairment can have features that mimic ASD because of certain qualitative differences in their social approach, social interaction, communication, and restrictive behaviours. However, it is important to note that VI and ASD can co-occur.

As you can see, the above list includes many conditions that need to be thought of, considered, and ruled out, before a diagnosis of ASD can be made. Nevertheless, this list is by no means exhaustive. Therefore, a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation is essential for an accurate diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder.