Unit II: Strategies for transition to inclusive classrooms

1. Adaptations in physical environment

2. Instructional adaptations across environments

3. Adaptations in Classroom practices and curricular and co curricular activities

4. Sensitization of the School environment

5. Assignments, examination and test taking strategies

1. Adaptations in physical environment

Practically all children and adolescents with ASD require adaptations in their school environments. Individuals with very severe symptoms or who have other associated disorders or disabilities require a high degree of adaptation and frequently require the intervention of special education teachers, either in the setting of a regular school or in special needs schools.

Nevertheless, even in the case of high-functioning children and adolescents with an average or above-average intellectual level, teachers often need to make certain adaptations to their teaching methodologies because characteristics such as inflexibility, literal thinking or social comprehension difficulties still have an impact on these individual’s school function.

What is more, generally speaking measures to facilitate socialisation with classmates or to reduce disruptive behaviours are also required. Later in life, as these adolescents with ASD start to become adults, they tend to seek out environments that are more in line with their interests and strong points, which can help achieve a greater level of academic and/or occupational adaptation.

1. Keep Materials Out of View When Not In Use

Some children, such those with autism or ADHD can become overwhelmed or overstimulated when presented with too much visual and tactile (things you can touch) information so it is important to reduce clutter.

Try to have a specific place for things (e.g., toys in a bin, papers and pens in a drawer, etc.). If you want your child to get through dinner or homework/classwork without distractions, move distracting material out of the environment or keep it in a closed container.

If you have the containers on shelves, (as is often the case in classrooms) it can be helpful to hang a cloth over the shelves so your child is not distracted by the actual bins (e.g. , wanting to go over to them, take the materials out of them, etc.).

2. Minimize What is On The Walls

Sometimes children with autism or ADHD, who are in a general education classroom, get easily distracted by all the artwork and decorations they see. This can actually happen with any child, not just those with ADHD or autism.

In a general education classroom, it is difficult to keep all these items covered up/not visible because children who do not get easily distracted by this type of input benefit from seeing artwork and decorations around the room and having open access to materials. Try to compromise so you are meeting all students’ needs.

You can keep the art-work and decorations in one spot, such as on a bulletin board (right outside the room or in a specific location in the room), rather than all over the room. The same would go for materials, as shown in the bookshelf images above.

3. Give the classroom or learning space clearly defined areas.

This is more applicable to classrooms that have different stations (e.g., reading area, seat-work area, computer area, play area, sensory area, etc.). You can use tape, room dividers, different color carpet (e.g., some carpet stores may donate left over pieces of carpet) or book shelves to section off areas.

Accommodating and modifying your classroom environment can help children be successful learners and be an active participant in classroom activities, but remember that deciding which accommodations or modifications you should use will be mostly dependent on the individual child and your teaching objectives.

2. Instructional adaptations across environments

TEACCH

Autism Teaching Methods: TEACCH (Treatment and Education of Autistic and Related Communication-Handicapped CHildren)

TEACCH was developed by psychologist Eric Schopler at the University of North Carolina in the 1960s; it is used by many public school systems today. A TEACCH classroom is structured, with separate, defined areas for each task, such as individual work, group activities, and play. It relies heavily on visual learning, strength for many children with autism and PDD. The children use schedules made up of pictures and/or words to order their day and to help them move smoothly between activities. Children with autism may find it difficult to make transitions between activities and places without schedules.

Young children may sit at a work station and be required to complete certain activities, such as matching pictures or letters. The finished assignments are then placed in a container. Children may use picture communication symbols -- small laminated squares that contain a symbol and a word -- to answer questions and request items from their teacher. The symbols help relieve frustration for nonverbal children while helping those who are starting to speak to recall and say the words they want.

This method of "structured teaching" is often less intensive than Applied Behavior Analysis or Verbal Behavior programs in the preschool years.

According to information previously published on its web site, TEACCH respects "the culture of autism" and embraces a philosophy that people with autism have "characteristics that are different, but not necessarily inferior, to the rest of us." It says, "The person is the priority, rather than any philosophical notion like inclusion, discrete trial training, facilitated communication, etc."

Drawbacks to this method: Social interaction and verbal communication may not be as heavily stressed as other teaching methods; TEACCH is more focused on accommodating a child's autistic traits than in trying to overcome them. Also, more research is needed into the effectiveness of TEACCH, especially in comparison to Applied Behavior Analysis and other teaching methods.

In contrast to the outcome studies of ABA published by Dr. Ivar Lovaas, TEACCH has not published comprehensive, long-term studies of its effectiveness in treating and educating children. A short-term study in 1998 found that young children who received four months of a home-based TEACCH program improved more than children who received no treatment at all.

Parents who want their child completely included in all classes with nondisabled children may not be happy with a TEACCH program. Some schools primarily use TEACCH in self-contained "autism classrooms," but it can be used in other settings.

The TEACCH program developed in North Carolina includes an array of services such as evaluations, parent training and support groups, social and recreation groups, counseling, and supported employment. However, these services may be missing from public schools in other states that have adopted this method for their autism classroom. You may wish to learn more about the North Carolina model to see how your school's TEACCH program measures up.

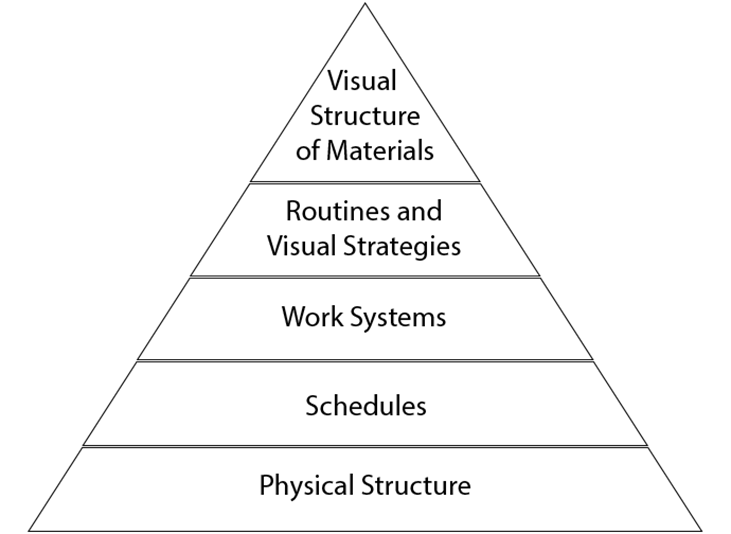

There are five elements of Structured Teaching that build on one another, and all emphasize the importance of predictability and flexible routines in the classroom setting. Division TEACCH developed a visual to illustrate the Structured Teaching components — the Structured Teaching pyramid:

Article 1: Physical structure in the school setting

This article describes the physical structure component of the Structured Teaching pyramid. Physical structure is the foundation of structured teaching and is helpful in ensuring that learning is occurring in the classroom.

Article 2: Visual schedules in the school setting

This article describes the visual schedule component of the Structured Teaching pyramid. A visual schedule communicates the sequence of upcoming activities or events through the use of objects, photographs, icons, words, or a combination of tangible supports.

Article 3: Work systems in the school setting

This article describes the work systems component of the Structured Teaching pyramid. A work system is an organizational system that gives a student with ASD information about what is expected when he/she arrives at a classroom location.

Article 4: Visual structure in the school setting

This article describes the visual structure component of the Structured Teaching pyramid. Visual structure adds a physical or visual component to tasks to assist students in understanding HOW an activity should be completed.

3. Adaptations in Classroom practices and curricular and co curricular activities

Curricular Activities:

Basically speaking activities encompassing the prescribed courses of study are called curricular or academic activities. In simple words it can be said that activities that are undertaken inside the classroom, in the laboratory, workshop or in library are called “curricular activities.” These activities are an integral part of the over-all instructional programme. Because in the organisation of these activities or programmes there lies active involvement of the teaching staff of the educational institution.

Curricular activities include:

(i) Classroom activities:

These are related to instruction work in different subjects such as classroom experiments, discussions, question-answer sessions, scientific observations, use of audio-visual aids, guidance programmes, examination and evaluation work, follow-up programmes etc.

(ii) Activities in the library:

It deals with reading books and magazines taking notes from prescribed and reference books for preparing notes relating to talk lessons in the classroom. Reading journals and periodicals pertaining to different subjects of study, making files of news-paper cuttings, etc.

(iii) Activities in the laboratory:

These refers to activities which are carried out in science laboratories, social science room (history and geography), laboratories in humanities (psychology, education, home science etc.).

(iv) Activities in the Seminars, workshops and conferences:

These activities refer to the presentations, discussions, performed by delegates and participants on emerging areas of various subjects of study in workshops, seminars and conferences.

(v) Panel discussion:

For enriching knowledge, understanding and experience of both the teachers and students panel discussion is essential, which would have be organised in the classroom situation. Organisation of this programme facilitates scope for interplay of expressions on the topic under discussion. After stating the various types of curricular activities it is essential to highlight the fact that academic or instructional work in any subject will be meaningless if it will not be accompanied by one or all of the above mentioned activities.

Co-Curricular Activities:

Broadly speaking co-curricular activities are those activities which are organised outside the classroom situation. These have indirect reference to actual instructional work that goes on in the classroom. Although no provision has been made for these activities in the syllabus but provision has been made for these in the curriculum.

As the modem educational theory and practice gives top most priority on all round development of the child there is the vitality of the organisation of these activities, in the present educational situation. So for bringing harmonious and balanced development of the child in addition to the syllabus which can be supplemented through curricular activities, but the CO- curricular activities play significant role. These activities are otherwise called as extra-curricular activities.

It is therefore said that the co-curricular or extra-curricular activities are to be given importance like the curricular activities. So now organisation of co-curricular activities is accepted as an integral part of the entire curriculum.

Types of Co-Curricular Activities:

Co-curricular activities are categorized in the following heads:

(i) Physical Development Activities:

These activities include games, sports, athletics, yoga, swimming, gardening, mass drill, asana, judo, driving, etc.

(ii) Academic Development Activities:

These activities include formation of clubs in relation to different subjects. Such as science club, history club, ecological club, economics club, geographical club, civic club etc. Besides this the other activities like preparation of charts, models, projects, surveys, quiz competitions etc. come under this category.

(iii) Literary Activities:

For developing literary ability of students the activities like publication of school magazine, wall magazine, bulletin board, debates, news paper reading, essay and poem writing are undertaken.

(iv) Cultural Development Activities:

The activities like drawing, painting, music, dancing, dramatics, folk song, fancy dress, variety show, community activities, exhibition, celebration of festivals, visit to cultural places having importance in local, state, national and international perspective come under this category.

(v) Social Development Activities:

For bringing social development among students through developing social values resulting in social service the following co-curricular activities are organised. Such as – NSS, girl guiding, red cross, adult education, NCC, boys scout, mass programme, social service camps, mass running, village surveys etc.

(vi) Moral Development Activities:

The co-curricular activities like organisation of extra mural lectures, social service, celebration of birth days of great-men of national and international repute, morning assembly should be organised. These activities bring moral development among individuals.

(vii) Citizenship Training Activities:

The activities like student council, student union, visits to civic institutions like the parliament, state legislatures, municipalities, formation of student self government, co-operative stores are essential for providing useful and valuable civic training.

(viii) Leisure Time Activities:

These activities are otherwise known as hobbies of different students. These include activities like coin-collecting, album making, photography, stamp collecting, gardening, candle making, binding, toy making, soap making, play modeling etc.

(ix) Emotional and National Integration Development Activities:

Under this category organisation of camps, educational tours, speech programmes, celebration of national and international days are included.

6 Steps to Adapting Curriculum and Instruction

1. Choose the activity.

2. Identify your curricular goals for this activity. What do you want the children to learn, to experience, to be engaged in?

3. What is your instructional plan for this activity? How do you want to present the information to the children?

4. Identify the children in your classroom who might need adaptations for this activity.

5. Based on your knowledge of each child’s goals and skills, choose and appropriate adaptation or group of adaptations. Start with the most natural, least intrusive adaptations.

6. Observe and adjust your adaptations as needed during the activity.

* A change in the type of adaptation used,

* A change in the amount of adaptation needed.

* A change in the number of adaptation used.

Possible Adaptations for children with Autism

Ø Establish a consistent routine.

Ø Verbally review the daily schedule. Provide picture cues as reminders.

Ø Provide visual cues in addition to auditory cues. For example, make a picture schedule or picture choice cards.

Ø Ask parents and therapist about the use of augmentative communication (sign language, communication boards).

Ø Verbally rehearse difficult situations. In other words, talk about what you will be doing and what you expect of the child.

Ø Warn in advance for transitions. Provide visual cues such as a sweat band for outdoor play or a napkin for snack.

Ø Accept non-speech communication. Watch for eye gaze (looking toward or away from items), body language, or facial expressions. Listen to the child’s behavior.

Ø Computers are wonderful tools for children with autism. Activities and Instruction are provided in short steps; they use consistent, non-threatening feedback; and they require no social interaction skills.

Ø Items such a shaving cream/gels are good as a calming utensils as well as for teaching writing techniques.

4. Sensitization of the School environment

Individuals with disabilities often are stigmatized, encountering attitudinal and physical barriers both in work and in daily life. Although federal legislation (e.g., Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990) protects the inherent rights of individuals with disabilities, that legislation cannot always protect them from subtle forms of discrimination and prejudice. School-age students with disabilities often have negative school experiences related to their having a disability, and school counselors, administrators, and teachers can help to create more positive school experiences that promote their academic, career, and personal/social growth. By examining the attitudes and behaviors of school staff and students as well as systemic factors related to the school, school counselors in collaboration with other school personnel can determine areas for intervention and respond accordingly.

Understanding attitudes

Negative attitudes and behaviors of students toward their peers with disabilities may occur for many reasons, but empirical research has not identified any specific causes. Nevertheless, assessing student attitudes is important prior to implementing any school-based intervention. Salend (1994) identified a number of methods for assessing the attitudes of regular education students toward students with disabilities, including sociograms, direct observation, and formal attitude assessments.

Although research identifying reasons for negative student attitudes is scarce, a number of explanations for negativity from educators toward students with disabilities have been proposed. Research cited previously (i.e., Praisner, 2003) suggests that one reason school personnel might possess negative attitudes toward students with disabilities is that they did not receive adequate training regarding those individuals and therefore feel unprepared to provide services to students with disabilities effectively. This theme has consistently emerged in literature related to both school counselors and teachers. School counselors surveyed by Milsom (2002) reported completing minimal formal training related to students with disabilities prior to being employed as school counselors and indicated they felt somewhat prepared to provide services to students with disabilities. Additionally, Forlin (2001) reported that teachers felt stressed when working with students with disabilities because they did not possess knowledge or feel competent. Finally, Pavri (2004) found that both special education and regular education teachers received little to no pre-service training related to effective inclusion for students with disabilities. In fact, special education teachers reported receiving less training in this area than did regular education teachers.

In addition to not feeling prepared, school personnel also face demands placed on them by superiors. Disability legislation (e.g., Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) and current educational reforms, including No Child Left Behind, create systems in which school personnel are held accountable for student outcomes. Forlin (2001) found that teachers reported high levels of stress when they felt they personally would be held accountable for the educational outcomes of students with disabilities. The teachers also worried that spending more time addressing the needs of students with disabilities would result in their having less time to focus on students without disabilities. "The highest levels of stress appear to come from a teacher's personal commitment to maintaining effective teaching for all students in their classes" (Forlin, p. 242).

Thus, understandably, negative attitudes seem to characterize educators who care about students and about being effective but who may have little control over or support for their work. Stress and frustration seem to be natural outcomes, in such situations. It seems likely that the majority of teachers would be more positive if they had more knowledge about students with disabilities and effective strategies for working with those students.

Interventions to improve attitudes

As advocates for students with disabilities, school counselors are positioned to take the lead in their buildings to ensure that these students have positive school experiences, develop skills for future academic and career success, develop social skills, and enjoy emotional health. A number of programs could be initiated in an effort to address the training needs of school personnel and to facilitate positive interactions among all students. Self-awareness is important, however, and school counselors can benefit from taking time to honestly assess their own beliefs about and attitudes toward students with disabilities prior to accepting or volunteering to work on school-based interventions. School counselors who possess negative attitudes might consider participating in professional development activities (see Milsom, 2002) to address their own biases. Because school counselors are responsible for meeting the needs of all students, comfort with and positive attitudes toward working with students with disabilities can be viewed as important qualities of a professional, ethical, and multiculturally competent school counselor.

5. Assignments, examination and test taking strategies

Learning to take tests can be an overwhelming process for many students. However, effective study and test-taking strategies are fundamental to school success and many career opportunities. Parents and educators should be aware of different test-taking strategies that can help reduce test anxiety and help children better perform in class.

Test taking is a challenge for most students. However for some individuals with disabilities, test taking can present specific obstacles. Student needs vary greatly, depending on the disability and type of test. Students themselves and disability service personnel are the best sources of information about strategies that work best.

General strategies for accommodating students with disabilities in testing activities include:

· alternative, quiet testing locations and distraction-free rooms

· alternate formats (e.g., oral presentations, projects, essay instead of multiple choice; written paper instead of oral presentation)

· well-organized tests with concise instructions

· alternative test formats

· extended test-taking time

· providing reading or scribe services

· use of a computer to complete tests

Provide a scribe.

A scribe would be an appropriate accommodation. However, the student will still

need to access the exam material. The scribe could serve a dual role as a

reader if the exam is in standard print format. A reader would not be necessary

if the exam is in Braille. Extended examination time should also be considered

as an additional accommodation.

Provide extended examination time.

Extended examination time is an appropriate choice. Students who need a reader,

for example, may take up to 2-3 times longer to complete the test. However,

this accommodation alone does not provide access to the exam content and

materials.

Provide a copy of the test in Braille.

If the student reads Braille, this is an appropriate accommodation. Adequate

planning to transcribe the material in a timely manner is essential. Scientific

and technical material typically requires a special form of Braille called

Nemeth code Braille. A discussion with the student and disabled student

services counselor would be important to organize this type of accommodation.

The student may also need assistance writing the exam, therefore a scribe

and/or extended exam time would be additional accommodations to consider.

Give the student an oral version of the

test.

An oral version of the test is an option, but may be challenging because of the

scientific content. The student will need access to all of the scientific

material on the exam.