Unit II: Sensory Integration & Occupational Therapy

1. Sensory Processing in ASD

2. Sensory Integration Therapy: principles, method & limitations

3. Development of motor skills

4. Activities of daily living (ADL)

5. Role of occupational therapist: early childhood to school years

1. Sensory Processing in ASD

Many people are familiar with the five senses of hearing, seeing, touching, tasting, and smelling. In addition to these five, there are two other senses, the vestibular and proprioceptive senses. The vestibular sense helps people with balance. The proprioceptive sense helps people be aware of where their bodies are in relation to other things (for example, people or objects near them.) Sensory processing is the ability to use all seven senses to take in, process, and give meaning to sensory information from the environment.

Sensory integration is the neurological process that organizes and gives meaning to the information that is received from the senses, allowing an individual to respond appropriately. For example, when someone reaches for the stove, feels the heat, withdraws his or her hand quickly, and says “ouch,” sensory integration is at play. In this example, the individual first feels the heat, then uses his or her muscles and bones to withdraw the hand, and lastly uses language to say “ouch.”

What are sensory processing difficulties?

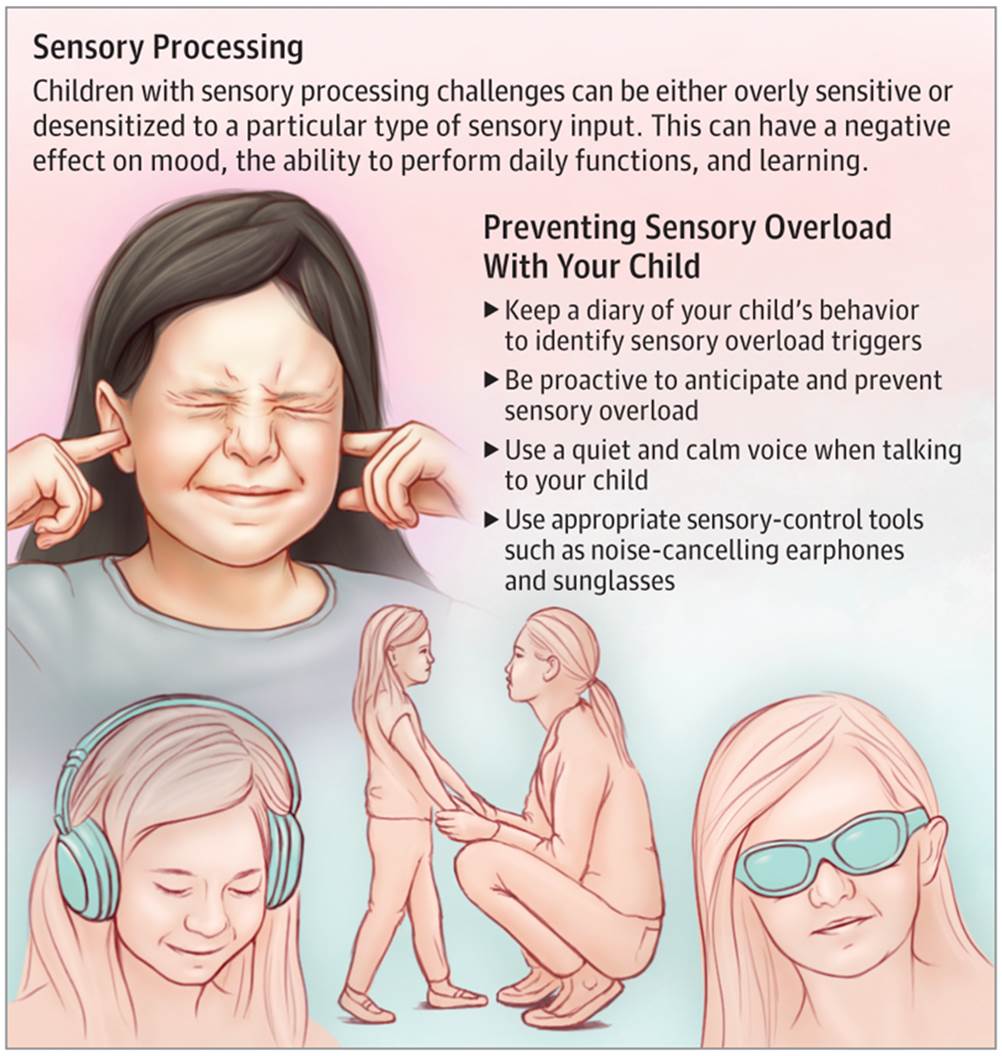

Sensory processing difficulty is a breakdown of the neurological process that organizes the sensory information. Many children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have difficulty processing and integrating sensory information and therefore may react differently than expected to information in the environment. Some children may overreact to environmental stimuli, while others may fail to notice or respond to environmental stimuli. A difficulty with processing sensory information can lead to difficulties with completing basic daily activities. For example, a child holding his hands over his ears and screaming as if in pain when the fire alarm sounds, or a child who seems to hear an airplane overhead and stop in his tracks before anyone else can hear it, is having difficult processing sensory information. (These children may also be struggling with other co-occurring conditions to ASD, such as anxiety.)

Tactile System

The tactile system includes nerves under the skin’s surface that send information to the brain. This information includes light touch, pain, temperature, and pressure. These play an important role in perceiving the environment as well as protective reactions for survival.

Dysfunction in the tactile system can be seen when an individual:

· withdraws from being touched

· refuses to eat certain ‘textured’ foods

· refuses to wear certain types of clothing

· complains about having one’s hair or face washed

· avoids getting one’s hands dirty (i.e., glue, sand, mud, finger-paint)

· uses one’s fingertips rather than whole hands to manipulate objects

A dysfunctional tactile system may lead to a misperception of touch and/or pain (hyper- or hypo-sensitive ) and may lead to self-imposed isolation, general irritability, distractibility, and hyperactivity.

Tactile defensiveness is a condition in which an individual is extremely sensitive to light touch. Theoretically, when the tactile system is immature and working improperly, abnormal neural signals are sent to the cortex in the brain which can interfere with other brain processes. This, in turn, causes the brain to be overly stimulated and may lead to excessive brain activity, which can neither be turned off nor organized. This type of over-stimulation in the brain can make it difficult for an individual to organize one’s behavior and concentrate and may lead to a negative emotional response to touch sensations.

Vestibular System

The vestibular system refers to structures within the inner ear (the semi-circular canals) that detect movement and changes in the position of the head. For example, the vestibular system tells you when your head is upright or tilted (even with your eyes closed). Dysfunction within this system may manifest itself in two different ways. Some children may be hypersensitive to vestibular stimulation and have fearful reactions to ordinary movement activities (e.g., swings, slides, ramps, inclines). They may also have trouble learning to climb or descend stairs or hills; and they may be apprehensive walking or crawling on uneven or unstable surfaces. As a result, they seem fearful in space. In general, these children appear clumsy. On the other extreme, the child may actively seek very intense sensory experiences such as excessive body whirling, jumping, and/or spinning. This type of child demonstrates signs of a hypo-reactive vestibular system; that is, they are trying continuously to stimulate their vestibular systems.

Proprioceptive System

The proprioceptive system refers to components of muscles, joints, and tendons that provide a person with a subconscious awareness of body position. When proprioception is functioning efficiently, an individual’s body position is automatically adjusted in different situations; for example, the proprioceptive system is responsible for providing the body with the necessary signals to allow us to sit properly in a chair and to step off a curb smoothly. It also allows us to manipulate objects using fine motor movements, such as writing with a pencil, using a spoon to drink soup, and buttoning one’s shirt.

Some common signs of proprioceptive dysfunction are:

· clumsiness

· a tendency to fall

· a lack of awareness of body position in space

· odd body posturing

· minimal crawling when young

· difficulty manipulating small objects (buttons, snaps)

· eating in a sloppy manner

· and resistance to new motor movement activities

Another dimension of proprioception is praxis or motor planning. This is the ability to plan and execute different motor tasks. In order for this system to work properly, it must rely on obtaining accurate information from the sensory systems and then organizing and interpreting this information efficiently and effectively.

2. Sensory Integration Therapy: principles, method & limitations

Sensory integration therapy, which was developed in the 1970s

by an OT, A. Jean Ayres, is designed to help children with sensory-processing

problems (including possibly those with ASDs) cope with the difficulties they

have processing sensory input. Therapy sessions are play-oriented and may

include using equipment such as swings, trampolines, and slides.

Sensory integration also uses therapies such as

deep pressure, brushing, weighted vests, and swinging. These therapies appear

to sometimes be able to calm an anxious child. In addition, sensory integration

therapy is believed to increase a child’s threshold for tolerating sensory-rich

environments, make transitions less disturbing, and reinforce positive

behaviors.

The five main senses are:

- Touch - tactile

- Sound - auditory

- Sight - visual

- Taste - gustatory

- Smell - olfactory

In addition, there are two other powerful senses:

a) vestibular (movement and balance sense)-provides information about where the head and body are in space and in relation to the earth's surface.

b) proprioception (joint/muscle sense)-provides information about where body parts are and what they are doing.

A child’s sensory processing is problematic if they are:

· Over-responsive – avoidance, caution and fearful

· Sensory seeking – impulsive and takes risks

· Under-responsive – withdrawn, passive or difficult to engage

Traditional sensory integrative therapy

Traditional sensory integrative therapy takes place on a 1:1 basis in a room with suspended equipment for varying movement and sensory experiences. The goal of therapy is not to teach skills, but to follow the child's lead and artfully select and modify activities according to the child's responses. The activities afford a variety of opportunities to experience tactile, vestibular, and proprioceptive input in a way that provides the "just right" challenge for the child to promote increasingly more complex adaptive responses to environmental challenges. The result is improved performance of skills that relate to life roles, e.g., player, student, (Schaaf & Anzalone, 2001). This type of intervention may be used along with other treatment approaches.

The main form of sensory

integration therapy is a type of therapy that places a

child in a room specifically designed to stimulate and challenge all of the

senses. During the session, the facilitator works closely with the child to

provide a level of sensory stimulation that the child can cope with, and

encourage movement within the room.

Sensory

integration therapy is

driven by four main principles:

• Just Right Challenge (the child must be

able to successfully meet the challenges that are presented through playful

activities)

• Adaptive Response (the child adapts his

behavior with new and useful strategies in response to the challenges

presented)

• Active Engagement (the child will want to

participate because the activities are fun)

• Child Directed (the child's preferences

are used to initiate therapeutic experiences within the session).

Children with lower sensitivity

(hyposensitivity) may be exposed to strong sensations such as stroking with a

brush, vibrations or rubbing. Play may involve a range of materials to

stimulate the senses such as play dough or finger painting.

Children with heightened sensitivity

(hypersensitivity) may be exposed to peaceful activities including quiet music

and gentle rocking in a softly lit room. Treats and rewards may be used to

encourage children to tolerate activities they would normally avoid.

Sensory integration therapy begins with a thorough evaluation and assessment of a child’s sensitivity to environment. This assessment is comprised of interviews with a child’s parents or caregivers, a health history, standard tests and observation in a clinical setting. The goal is to determine where deficits in a child’s sensory perception are and what interventions will help a child adapt and react to their environment.

A therapist will administer the Sensory Integration and Praxis Tests (SIPT). During the assessment, the therapist will evaluate:

· Body positioning in relation to space and objects

· Existing sensory-seeking behaviors

· Eye-hand coordination

· Modulation

· Motor planning (praxis)

· Movement perception

· Planning and sequencing actions

· Reaction to touch, sounds and textures

· Spontaneous activity and play

· Visual perception and eye movement

The therapist will determine activities that encourage organized responses to sensory input. Activities are practiced in a repetitive and continuous fashion so children can learn and retain the process. They learn how to self-regulate their responses, achieve a comfort level with sensations, and understand how the senses work collectively.

Sensory integration therapy is often disguised as “fun” for the child. The goal of therapy is to allow children to explore in an unencumbered environment that allows them to fine-tune their interpretations and responses. For example, a child that is uncomfortable with rough surfaces may play with grains of rice, so he or she can get used to its texture – which in turn neutralizes his or her discomfort with the sensations.

Therapy is ultimately successful when the child realizes the value of the outcome enough to continually use the learned process.

Sensory integration therapy can make a real difference by helping individuals to manage their sensitivities and cravings. The American Occupational Therapy Association describes several types of remediation that can help with both sensory challenges and the performance challenges that can go along with them:5

- Remedial intervention involving the use of sensory and motor activities and equipment (e.g., swinging, massage)

- Accommodations and adaptations wearing earplugs or headphones to diminish noise, or using a textured sponge in the shower

- Sensory diet programs involving a daily menu plan which includes individualized, supportive sensory strategies (e.g., quiet space, aromatherapy, weighted blanket), physical activities, and tangible items (e.g., stress balls or other items for distraction)

- Environmental modifications to decrease sensory stimulation such white noise machines, art work, and other types of decor/furnishings

- Education for involved individuals, including family members, caregivers, and administrators, about the influence of sensory functions on performance and ways to minimize their negative impact on function

In the long run, sensory integration therapy can decrease the need for adaptations and help individuals become more functional at home, at school, and in the workplace.

Limitations:

When a child begins sensory integrations therapy, he or she can receive too much sensory stimulation, which can result in reactions which could be disruptive, like willfulness or frustration. For this reason, a therapist – as well as parents or caregivers – must monitor a child’s reactions to counteract those reactions.

Additionally, some sensory integrations techniques might make a child uncomfortable.

All of these situations can be mitigated when a trained occupational therapist implements a highly-structured plan of intervention that is both well-organized and fun for the child.

3. Development of motor skills

Studies have shown autistic children can have varying degrees of difficulty with fine and gross motor skills. Another study suggests autistic children could be six months behind in gross motor skills compared to their peers, and a year behind in fine motor skills.

These are difficulties that can be overcome, but are believed to exist due to the neurological differences in autistic children and their challenges with sensory processing.

Difficulties with gross motor skills may involve anything that relies on balance, body awareness, and motor control. This could include playing sports, riding a bike, or simply carrying books to class.

Difficulties with fine motor skills may include anything that relies on using small muscles in the hands. Since we use our hands for so many things in life, this could include anything from signing one’s name, to playing an instrument.

These challenges with motor development can be treated if detected early enough.

Addressing

Challenges With Motor Skills Development

After a professional has observed a child’s unique difficulties with motor

skills development, a treatment plan may be developed to address their specific

needs.

Autistic children are not all challenged by motor skills development to the same degree. Some have pronounced difficulty with fine motor skills, some are more challenged by gross motor skills, while others have difficulty with both.

Parents should be familiar with the treatment plan designed for their child, and take an active role in assisting them with prescribed therapies. It’s also recommended that parents be proactive in ensuring motor skill development is something that gets addressed early on in this child’s life, because it’s often neglected in therapy programs

Occupational therapists can help your child achieve goals during therapy sessions, but there are specific activities and strategies that can be done at home to help develop and strengthen your child’s fine motor ability.

· Look for hidden objects in putty, Playdoh or clay

· Make slime or another resistive texture to allow the child to pull apart and squeeze

· Have the child look for hidden objects in different tactile media (i.e. reaching into the sand and pulling out a marble)

· Put snacks in snack bags or other plastic containers that would allow the child opportunities to manipulate snaps.

· Use a squeeze toy .

· Use magnet tiles or construction blocks to pull apart and piece together.

· Put Velcro strips on the back pieces of puzzles for there to be some resistance when pulling.

· Use clothespins or tongs to pick up small manipulatives to sort.

· Use a squeeze bottle to water plants.

· Put coins into a piggy bank.

· Lace blocks/beads of various sizes onto string or pipe cleaners

· “Write” in clay, sand, dirt or other tactile media

· Use broken crayons to facilitate a proper pencil grasp

· Peel stickers

· Use a hole punch

· Cut out simple shapes or along a line

· Build letters out of wiki stix or pipe cleaners

Children with autism spectrum disorder typically require additional time to acclimate to new situations and accept changes in their typical routine. Fine motor skills may be challenging to address because children with ASD can become overwhelmed by the different aspects of an activity so continued exposure, persistence and success with a task can make children with ASD all the more willing to participate in different fine motor activities.

4. Activities of daily living (ADL)

Each day we wake up and complete a familiar routine of activities of daily living (ADLs). This may involve eating breakfast, showering, brushing our teeth, packing our lunch, and then heading out the door. Throughout our day we complete several tasks that foster our independence. However for individuals with autism, these daily tasks may be challenging. In order to live independently in society, it is crucial that individuals learn how to perform daily living skills. Activities of daily living include dressing, feeding, toileting, etc. These activities promote independence but why do many individuals with autism have difficulty performing these tasks. A person with autism must learn ADLs differently, taking into account sensory, motor, and social issues. We might have watched our siblings or parents brush our hair then learning how to do it ourselves from imitation. Individuals with autism do not necessarily learn these skills through imitation naturally. Individuals with autism may not necessarily want to do these skills “all by themselves” or care what their peers might think about their inability to perform these skills. Sensory issues may prohibit a child from trying new foods due to the smell or texture, which may result in issues with self-feeding. Motor skills are crucial to independently completing ADLs, if an individual has difficulty opening the toothpaste, the overall skill of brushing his teeth will be difficult.

What Are the Activities of Daily Living?

Adaptive behavior includes communication, social, and daily living skills. Activities of daily living include activities surrounding personal hygiene, meal preparation, and money and time management. The benefits of adaptive behavior extend to individuals and their communities, but some children may face challenges in developing ADLs and may require additional support.

Examples of ADLs include maintaining proper personal hygiene, meal preparation, and money and time management. Performing these tasks require foundational cognitive, motor, and perceptual abilities. However, children with autism may have difficulty due to behavioral challenges like limited receptive language, and weak imitation skills. Additionally, certain behaviors can hinder ADL acquisition in autistic children, including tantrums and distractedness.

Ten Ways to Build Your Child’s Independence

1. Strengthen Communication

If your child struggles with spoken language, a critical step for increasing independence is strengthening his or her ability to communicate by building skills and providing tools to help express preferences, desires and feelings. Consider introducing Alternative/Augmentative Communication (AAC) and visual supports. Common types of AAC include picture exchange communication systems (PECS), speech output devices (such as DynaVox, iPad, etc.).

2. Introduce a Visual Schedule

Using a visual schedule with your child can help the transition from activity to activity with less prompting. Review each item on the schedule with your child and then remind him or her to check the schedule before every transition. Over time, he or she will be able to complete this task with increasing independence, practice decision making and pursue the activities that interest him or her.

3. Work on Self-Care Skills

Introduce self-care activities into your child’s routine. Brushing teeth, combing hair and other activities of daily living (ADLs) are important life skills, and introducing them as early as possible can allow your child to master them down the line. Make sure to include these things on your child’s schedule so he or she gets used to having them as part of the daily routine.

4. Teach Your Child to Ask for a Break

Make sure your child has a way to request a break – add a “Break” button on his or her communication device, a picture in his or her PECS book, etc. Identify an area that is quiet where your child can go when feeling overwhelmed. Alternatively, consider offering headphones or other tools to help regulate sensory input. Although it may seem like a simple thing, knowing how to ask for a break can allow your child to regain control over him or herself and his or her environment.

5. Work on Household Chores

Having children complete household chores can teach them responsibility, get them involved in family routines and impart useful skills to take with them as they get older. If you think your child may have trouble understanding how to complete a whole chore, you can consider using a task analysis. This is a method that involves breaking down large tasks into smaller steps. Be sure to model the steps yourself or provide prompts if your child has trouble at first!

6. Practice Money Skills

Learning how to use money is a very important skill that can help your child become independent when out and about in the community. No matter what abilities your child currently has, there are ways that he or she can begin to learn money skills. At school, consider adding money skills to your child’s IEP and when you are with your child in a store or supermarket, allow him and her to hand over the money to the cashier. Step by step, you can teach each part of this process. Your child can then begin using these skills in different settings in the community.

7. Teach Community Safety Skills

Safety is a big concern for many families, especially as children become more independent. Teach and practice travel training including pedestrian safety, identifying signs and other important safety markers; and becoming familiar with public transportation. The GET Going pocket guide has many useful tips to help individuals with autism navigate public transportation. Consider having your child carry an ID card which can be very helpful to provide his or her name, a brief explanation of his or her diagnosis, and a contact person. You can find examples of ID cards and other great safety materials.

8. Build Leisure Skills

Being able to engage in independent leisure and recreation is something that will serve your child well throughout his or her life. Many people with autism have special interests in one or two subjects; it can help to translate those interests into age appropriate recreational activities.

9. Teach Self-Care during Adolescence

Entering adolescence and beginning puberty can bring many changes for a teen with autism, so this is an important time to introduce many hygiene and self-care skills. Getting your teens into the habit of self-care will set them up for success and allow them to become much more independent as they approach adulthood. Visual aids can be useful to help your teen complete his or her personal hygiene routine each day. Consider making a checklist of activities to help your child keep track of what to do and post it in the bathroom. This can include items such as showering, washing face, putting on deodorant and brushing hair. To stay organized, you can put together a hygiene “kit” to keep everything your teen needs in one place.

10. Work on Vocational Skills

Starting at age 14, your child should have vocational skills included on his or her IEP as a part of an individualized transition plan. Make a list of his or her strengths, skills and interests and use them to guide the type of vocational activities that are included as objectives. Consider all the ways up to this point that you have been fostering your child’s independence: communication abilities, self-care, interests and activities and goals for the future.

Mastering ADLs is crucial to one’s general well-being, and the responsibility of teaching children these skills should not be taken lightly. With this in mind, parents and behavior specialists can work together to teach the skills that will help children grow up to become responsible and independent adults.

5. Role of occupational therapist: early childhood to school years

Occupational therapy (OT) helps people work on cognitive, physical, social, and motor skills. The goal is to improve everyday skills which allow people to become more independent and participate in a wide range of activities.

Occupational therapists work to promote, maintain, and develop the skills needed by students to be functional in a school setting and beyond. Active participation in life promotes:

- learning

- self-esteem

- self-confidence

- independence

- social interaction.

Occupational therapists use a holistic approach in planning programmes. They take into account the physical, social, emotional, sensory and cognitive abilities and needs of students.

In the case of autism, an occupational therapist works to develop skills for handwriting, fine motor skills and daily living skills. However, the most essential role is also to assess and target the child’s sensory processing disorders. This is beneficial to remove barriers to learning and help the students become calmer and more focused.

OT’s working with children who have a sensory processing disorder often have postgraduate training in sensory integration.

Sensory integration therapy is based on the assumption that the child is either “over stimulated” or “under stimulated” by the environment. Therefore, the aim of sensory integration therapy is to improve the ability of the brain to process sensory information so that the child will function better in his/her daily activities.

Children are often prescribed a sensory diet/lifestyle by the occupational therapist.

For people with autism, OT programs often focus on play skills, learning strategies, and self-care. OT strategies can also help to manage sensory issues.

The occupational therapist will begin by evaluating the person's current level of ability. The evaluation looks at several areas, including how the person:

- Learns

- Plays

- Cares for themselves

- Interacts with their environment

The evaluation will also identify any obstacles that prevent the person from participating in any typical day-to-day activities.

Based on this evaluation, the therapist creates goals and strategies that will allow the person to work on key skills. Some examples of common goals include:

- Independent dressing

- Eating

- Grooming

- Using the bathroom

- Fine motor skills like writing, coloring, and cutting with scissors

Occupational therapy usually involves half-hour to one-hour sessions. The number of sessions per week is based on individual needs.

The person with autism may also practice these strategies and skills outside of therapy sessions at home and in other settings including school.

Some OTs are specifically trained to address feeding and swallowing challenges in people with autism. They can evaluate the particular issue a person is dealing with and provide treatment plans for improving feeding-related challenges.

The overall goal of occupational therapy is to help the person with autism improve their quality of life at home and in school. The therapist helps introduce, maintain, and improve skills so that people with autism can be as independent as possible.

These are some of the skills occupational therapy may foster:

- Daily living skills, such as toilet training, dressing, brushing teeth, and other grooming skills

- Fine motor skills required for holding objects while handwriting or cutting with scissors

- Gross motor skills used for walking, climbing stairs, or riding a bike

- Sitting, posture, or perceptual skills, such as telling the differences between colors, shapes, and sizes

- Awareness of their body and its relation to others

- Visual skills for reading and writing

- Play, coping, self-help, problem solving, communication, and social skills

By working on these skills during occupational therapy, a child with autism may be able to:

- Develop peer and adult relationships

- Learn how to focus on tasks

- Learn how to delay gratification

- Express feelings in more appropriate ways

- Engage in play with peers

- Learn how to self-regulate