Unit III: Social Cognition

1. Teaching Emotion

2. Developing Self concept

3. Understanding social situations

4. Teaching social referencing

5. Developing Interpersonal Skills

1. Teaching Emotion

Humans have six basic emotions – happiness, surprise, sadness, anger, fear and disgust. We also experience more complex feelings like embarrassment, shame, pride, guilt, envy, joy, trust, interest, contempt and anticipation.

The ability to understand and express these emotions starts developing from birth.

From around two months, most babies will laugh and show signs of fear. By 12 months, a typically developing baby can read your face to get an understanding of what you’re feeling. Most toddlers and young children start to use words to express feelings – although you might see a tantrum or two when their feelings get too big for their words!

Throughout childhood and adolescence, most children continue building empathy. They also build skills to manage their emotions and recognise and respond to other people’s feelings.

By adulthood, people are usually able to quickly recognise subtle emotional expressions.

Recognizing the emotions of others

Since people with autism often have difficulty reading the emotions of others, it can be difficult for them to interact appropriately in social situations. Children with autism may experience a difficulty in recognizing facial expressions, the tone of voice of another person, or their body language. These characteristics can tell us a lot about the emotions of another person, and developing these skills can help children with autism recognize the feelings of others as well.

Facial expressions. To help children with autism to recognize the facial expressions of others, it can be helpful to practice identifying them in a context that doesn’t have as much pressure as a real social situation. Identifying facial expressions in a context with less pressure allows children to build the knowledge and confidence to put these skills to use in daily life. A 2015 study of a teaching strategy for emotions showed that children with autism are able to differentiate between emotions, they just require more prompting to identify the appropriate label. In this study, they practiced identifying emotions in different situations through photos. For example, they would be asked to identify the correct emotion card to the correct situation card (such as a boy at a birthday party matched to a happy face) with varying levels of prompting. This study showed that children with autism can identify emotions after sufficient prompting and practice.

Eye contact and eye movements. People with autism often struggle with eye contact, which can in turn effect their ability to read facial expressions and communication through eye movements. Temple Grandin addresses this point in her article Social Problems: Understanding Emotions and Developing Talents, “I had no idea that people communicated feelings with their eyes. I also did not know that people get all kinds of little emotional signals which transmit feelings.” As a person with autism, Temple Grandin explains her difficulty in recognizing that people communicate emotions in a variety of ways. She then goes into detail about the ways that she tends to recognize the emotions of others during social interactions. Using her memory, she scans her mind for a social situation that was similar to the one she is currently in. She can then use her previous experiences to guide her through the current one.

Older children with autism can adopt this same idea by thinking about a time when they interacted with someone who may have been angry, sad, nervous, or happy. Likewise, they can think about other situations when they felt sad, angry, nervous, or happy. They can use the ideas from previous situations and apply them to their current situation to identify their own feelings or the feelings of others.

Tone of voice. Emotions can be displayed in more ways than just our facial expression and eye movements. Teaching children with autism the various ways that people display their emotions can be helpful by giving them multiple pathways to understanding the emotions of another person. There are various ways to familiarize children about how the tone of voice changes the meaning and emotions behind a sentence.

- One way to do this is to sit down with your child or student, and read aloud a book that they enjoy. Pick out a sentence or two within the book and read it using different tones of voice, and explain how the tone you are using changes the emotion behind the sentence. You can exclaim the sentence angrily, exclaim excitedly, form it as a question, say it nervously, or say it with a sad tone. Each time, ask the child to identify the emotion behind the sentence. Explain why, and emphasize that the same sentence can have a wide variety of meanings depending on the tone that is used.

- Another way to do this is to use a recording. Record yourself or others saying different sentences with different tones, and ask the child what emotion or feeling they thought was behind the sentence and why. Then, have the child practice using tones themselves! Ask them to say something in a sad voice, an excited voice, an angry voice, or a nervous voice. These exercises can help familiarize children with the different tones people use to communicate their feelings, and can help them become aware of their own tone of voice in conversation.

Body language. Some children with autism excel at identifying body language because it doesn’t require eye contact, however this isn’t universal for all children with or without autism. One simple way to familiarize children with body language is to draw cartoons. To do this, sit down with the child and draw a variety of cartoons with different body language; confused while scratching their head, mad while stomping their feet, excited while jumping up and down, etc. Ask the child what emotion they think is being displayed. Then you can ask the child to draw their own cartoons of someone who is happy, mad, excited, nervous, or confused through their body language. Having them create their own cartoons can help them develop ownership of the topic and help them relate these ideas to real life situations.

Showing and communicating emotion

Communicating our feelings can be challenging for everyone, but especially so for children with autism. There are different ways that children with autism can communicate their feelings in a healthy way. All children need a way to express how they are feeling, so here are a couple of suggestions on how to help children communicate their emotions.

Communicating feelings. For non-verbal children, emotions can become even more overwhelming if they do not have access to any means of communication. Assistive technology or sign language can be helpful for children to communicate their feelings if the child has access to them. Often times, assistive technology will contain ways to communicate feelings by pushing a button or pointing. Likewise, children who are fluent in sign language are often taught to express their emotions via sign.

Social stories. Social stories have so many great uses for a wide variety of children in and out of school, and they can help children identify and communicate their emotions. When sharing a social story with a child with autism, outline a situation that results in an emotion. For example, it could be as simple as a story of a mother telling a child to do their chores, and the child getting angry or sad.

The social story should consist of a situation that the child can relate to, so if they don’t do chores at home, perhaps a different story should be used. After reading the story to the child, ask them what emotion the character is displaying and why they might feel that way. One way to emphasize how to regulate emotions is to show one story of a child getting angry and having an emotional outburst, and explaining that there are other ways to express our feelings. Then, show the same story with a different ending where the child sits down and communicates their feelings with the other person in a calm way. Emphasize that it is okay to have the emotions that are being displayed, but the child in the second story is communicating their emotions in a way that is beneficial to both parties.

Regulating emotions

Many times, emotional outbursts are the result of becoming frustrated because children cannot communicate their feelings to others. The techniques provided above should help children to identify the emotions of others and communicate their own emotions. However, if the child still struggles to regulate their own emotions, there are other ways to prevent emotional outbursts. These are just a few suggestions of what may help children to regulate their emotions, but these should be individualized for the needs of each child.

Practice in recognizing emotions. Of course, practicing how to recognize our own emotions can help us to regulate them. Recognizing that you are feeling angry, sad, or nervous can help you to find solutions to your emotions. For example, when I am feeling nervous, I like to draw or write. This is a healthy way to channel my emotions when I am able to recognize what I am feeling. This is often the case for children with autism as well. By using the techniques above to help identify the emotions of others and communicate their own emotions, we can help children identify things that may relax them and help them regulate the ways they are feeling. Every person likes something different to help them regulate their emotions, so it can be helpful for teachers and parents to guide children in recognizing what helps them.

Mindfulness. Mindfulness is a great technique for regulating emotions and relaxing. Studies have shown that meditating makes you all around more relaxed and able to deal with complex situations that occur throughout the day.

2. Developing Self concept

The concept of self is notoriously difficult to define and different notions and theories of the self have been proposed by a variety of disciplines all interpreting concepts of self and identity in various ways. We adopt the definition advanced by neuroscientists Kircher and David [1] who interpret the self as ‘the commonly shared experience, that we know we are the same person across time, that we are the author of our thoughts/actions, and that we are distinct from the environment’ (p.2). In cognitive neuroscience literature, operational definitions of the self are used which are measurable by experimental methods including self recognition, self and other differentiation, body awareness, awareness of other minds, awareness of self as expressed in language and important concepts such as autobiographical memory and self narrative. There is significant interest in the role of the self and possible abnormalities associated with the self, as causally implicated in autism. In this paper we review developmental perspectives of self and self-related functions with reference to their neuroanatomical basis and investigate the possible causes for atypical self-development in Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD).

Self-esteem refers to an individual’s opinion of him or herself. People with healthy self-esteem trust their own instincts and abilities, believe that they are worthy of good things happening to them, and are confident that, with effort, they can accomplish any necessary or desired task. Unhealthy self-esteem can range from a dislike of oneself to an over-inflated self-opinion.

Research has shown that an individual’s self-esteem strongly influences his or her interpersonal relationships, behavior, and learning. Unhealthy self-esteem has been linked to abusive and/or dysfunctional relationships, academic troubles, depression, and even violence and crime. Healthy self-esteem is important because individuals who are confident can cope better when things go wrong or not as expected. Confidence, and in turn self-esteem, grows when individuals experience success.

Autistic teenagers will probably need your help to build their self-identity. Building a positive self-identity is important for your child because it also helps with your child’s self-esteem and self-confidence.

Here are some practical ideas that can help.

Talking about diversity

You can talk with your child about how everybody has their own strengths,

interests and challenges – which is what makes us interesting. This can help

your child see themselves as valuable and worthwhile.

You can also help your child understand that people can look, speak, think or act differently from each other – and this is OK.

You could turn this into a social story. The professionals working with your child will be able to help.

Meeting others

If your child joins an activity that they enjoy, like a sports club or a band,

this can help them build a better sense of their strengths, what they enjoy and

where they fit in. It’s also a good chance for your child to develop and

practise their social skills and mix with teenagers who don’t have

autism.

Getting involved with other autistic teenagers can help your child to understand more about autism and how it’s part of other people’s identities. Your child can share their own experiences with an understanding peer group.

Thinking about ‘me’

You can encourage your child to think about:

- what they like and don’t like

- their personality – for example, whether they’re generous, artistic, polite and so on

- what words they would use to describe themselves to others.

One way to get your child thinking about themselves is to help your child create an ‘All about me’ book. This might include pictures of things your child likes, pictures of friends or things about their hobbies and achievements. Drawings or craft creations from when your child was younger can remind your child of past experiences. Things like school reports can help your child think about past and current achievements.

When your child comes up with a list of words to describe themselves, these can go into their book.

Knowing about family

Your child’s self-identity also comes from knowing about their family. You

could show your child things like family photographs and include these in their

‘All about me’ book too.

It might also help your child to hear about your experiences of growing up and being a teenager, especially if your child doesn’t have a lot of support from peers and friends.

3. Understanding social situations

One of the core aspects of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is social dysfunction. This can manifest in a range of behaviors, from completely avoiding any sort of personal interaction at all… to completely monopolizing conversations on a single topic that nobody other than the person speaking seems to be very interested in.

There is no fixed pattern to social dysfunction, but it’s almost always one of the major identifiers of ASD and often the one that stands out the most when interacting with someone on the spectrum.

For high-functioning autistic individuals, these social skills deficits can be so minor as to be almost entirely unnoticeable in casual conversation. People with HFA (high-functioning autism) commonly adopt coping methods or have the ability to acquire social skills to fit in better. They are often able, with proper training (which often includes components of applied behavior analysis), to make significant progress in social interactions. Nonetheless, at some level, even high-functioning autistics almost always struggle with some discomfort or ineptitude in social interactions.

Many children and adults on the autism spectrum need help in learning how to act in different types of social situations. They often have the desire to interact with others, but may not know how to engage friends or may be overwhelmed by the idea of new experiences.

Building up social skills with practice can help enhance participation in the community and support outcomes like happiness and friendships. We have compiled social skills tips and information from experts, teachers, and families, along with useful tools to help enhance opportunities to be part of the community.

Social skills are the rules, customs, and abilities that guide our interactions with other people and the world around us. In general, people tend to “pick up” social skills in the same way they learn language skills: naturally and easily. Over time they build a social “map” of how to in act in situations and with others.

For people with autism it can be harder to learn and build up these skills, forcing them to guess what the social "map" should look like.

Social skills development for people with autism involves:

- Direct or explicit instruction and "teachable moments" with practice in realistic settings

- Focus on timing and attention

- Support for enhancing communication and sensory integration

- Learning behaviors that predict important social outcomes like friendship and happiness

- A way to build up cognitive and language skills

Strategies for helping autistic children develop social skills

Autistic children can learn social skills, and they can get better at these skills with practice. These ideas and strategies can help you build your child’s social skills:

- practice play

- praise

- role-play

- social skills training

- social stories

- video-modelling

- visual supports.

4. Teaching social referencing

Affective impairments are some of the earliest signs of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). These impairments disrupt the frequency and manner in which children with ASD initiate and respond to affective cues (e.g., facial cues, vocal displays of emotions, gestures). Specifically, children with ASD have difficulties with social referencing.

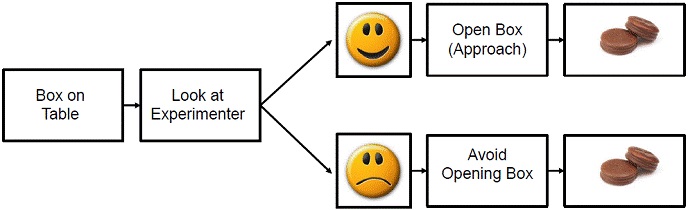

Social referencing is responding to other people’s facial cues. Imagine you walk into a room, see something ambiguous in the corner, you see someone in the room and he has a terrified look on his face. What do you do? I know what I wouldn’t do – approach the ambiguous object! Seeing the person’s facial cues helps provide information about the environment, and in this case, provides information to stay away from the ambiguous object. Analogously, positive facial cues such as smiling or nodding tell us that ambiguous objects are safe and, possibly, rewarding too.

From a behavioral standpoint, social referencing represents a two link behavior chain, where the first link consists of looking towards the adult’s face upon encountering an ambiguous stimulus, and the second link consists of approaching the stimulus when presented with positive facial cues and avoiding the stimulus when presented with negative facial cues. Children with ASD show difficulties in looking at the adult upon encountering an ambiguous stimulus, as well as in using the adult’s facial cues to guide their behavior.

Here is how social referencing plays a role in your child’s development:

· Social referencing is a critical component of your child’s emotional development. Your child will start learning the meanings of different emotive expressions, the words and sounds that follow, and how to associate with things.

· Social referencing is an important part of the decision making and will build your child’s confidence in your inputs. This mechanism develops into a process that forms the basis of their decision-making skills in life.

· Social referencing in toddlers also lays down the foundation for complex thought and understanding the connotations of different emotive expressions. Although it is not obvious at that age, the foundation laid down at home, and other social environments will have a profound influence on the development of the child.

Whether you are aware of it or not, social referencing is an ongoing developmental process in children. Your emotional states, gestures, actions and the situations that come up in the family are constantly working as social referencing. By being aware of it and controlling your actions, it is possible to use it for your child’s benefit. Here is how:

· Use plenty of facial expressions while interacting and playing with your child both when home and outside. Let your expressions be clear in the message that you are trying to convey, so he knows exactly how to map each expression to each emotion. This also applies to spontaneous events and things that catch you off guard and your untended, instinctive reaction.

· Your behaviour around others and social situations also have a significant influence on what your child learns from it. If your tone of voice and body language doesn’t sync, it could confuse the child. For example, if you speak to a neighbour or another person with a smile and immediately change your expression after they leave or show annoyance, your child will instantly pick on the ambiguity and get confused.

· Social referencing is very useful in building healthy eating habits in children. You can let your child know which foods are healthy and which should be consumed in moderation all through your expressions.

· Your reactions towards people, events and situations will imprint strongly on your child. Therefore practice being mindful and calm even under pressure and try not to lose it hysterically. On the other hand, it’s also important to teach him that feeling hurt and crying and expressing sadness is also an important thing.

5. Developing Interpersonal Skills

Children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are well known to have difficulties communicating at an interpersonal level with others. In schools, this can present a challenge for teachers where learning is very dependent on the relationships they can build with students and students can build with each other. The difficulties individuals with ASD encounter include recognizing social cues such as those derived from eye contact, gestures, smiles, and similar ways of communicating nonverbally, as well as those obtained from interacting verbally with others such as being able to engage in reciprocal interactions, understanding others’ perspectives, and recognizing others’ emotional states. Other difficulties that have been well documented include restrictive and repetitive patterns of behavior, fixated interests, and difficulties adjusting to changes in routines. These patterns of behavior emerge in early childhood and have been characterized as a lack of understanding of not only one’s mind but also the minds of others—or what is commonly referred to as a theory of mind (ToM). Alongside this theoretical lens, there are also neuroscientific perspectives that are helpful to consider.

Aim to teach children good practice in areas including:

· The use of appropriate greetings.

· The ability and willingness to initiate activities with peers and other people.

· Willingness to join an activity with peers and other people.

· The ability to begin and continue a conversation without too many distractions.

· The use of an appropriate amount of assertiveness to communicate needs, desires, beliefs and ideas.

· Resolving conflict and accept conflict resolution appropriately. Realising and understanding a concept of what is fair and what is unfair.

· Using negotiation and compromise appropriately as tools to achieve a desired goal and resolve conflict.

· Understanding non-verbal signals from others, body language, facial expressions etc.

· Displaying appropriate non-verbal communication.

· Participating appropriately in group situations, being neither too passive or aggressive

· Being aware of the personal space of others.

· Understanding different styles of language in different situations and to different people.

One of the most difficult interpersonal skills for children to adopt is conflict resolution. This is an advanced interpersonal skill as it requires prerequisite skills such as good listening and understanding of verbal and non-verbal communications.