Unit1: Concept of Growth and Development

1.1 Principles of Growth and Development

1.2 Growth and Development – Typical and Atypical (Physical/Individual difference)

1.3 Development and deviations (Educational – Lifespan Phase) i. Pre-natal stage ii. Preschool stage iii. School stage iv. Pre-vocational stage

1.4 Intelligence & Developmental Assessment

1.5 Types of Intelligence Test

1.1 Principles of Growth and Development

Growth: can be defined as an increase in size, length, height and weight or changes in quantitative aspect of an organism/individual.

Hurlock has defined Growth as “change in size, in proportion, disappearance of old features and acquisition of new ones”.

Development: is a series of orderly progress towards maturity. It implies overall qualitative changes resulting in the improved functioning of an individual.

According to Crow and Crow (1965) development is concerned with growth as well as those changes in behavior which results from environmental situation.”

Principles of Growth and Development

From the scientific knowledge gathered through observation of children, some principles have emerged. These principles enable the parents and the teachers to understand how children develop. What is expected of them? How to guide them and provide proper environment for their optimum development? It seems that the process of development is operated by some general principles. These rules or principles may be named as the principles of development. Some of these principles are briefly explained below:

1. Principle of Continuity: Development is a process which begins from the moment of conception in the womb of the mother and goes on continuing till the time of death. It is a never ending process. The changes however small and gradual continue to take place in all dimensions of one’s personality throughout one’s life.

2. Principle of Individual differences: Every organism is a distinct creation in itself. Therefore, the development which undergoes in terms of the rate and outcome in various dimensions is quite unique and specific. For example, all children will first sit up, crawl and stand before they walk. But individual children will vary in regard to timing or age at which they can perform these activities.

3. Principle of lack of uniformity in the developmental rate: Though development is a continuous process it does not exhibit steadiness and uniformity in terms of the rate of development in various dimensions of personality or in the developmental periods and stages of life. Instead of steadiness, development usually takes place in fits and starts showing almost no change at one time and a sudden spurt at another. For example, shooting up in height and sudden change in social interest, intellectual curiosity and emotional make-up.

4. Principle of uniformity of pattern: Although there seems to be a clear lack of uniformity and distinct individual differences with regard to the process and outcome of the various stages of development, yet it follows a definite pattern in one or the other dimension which is uniform and universal with respect to individuals of a species. For instance, the development of language follows a somewhat definite sequence quite common to all human beings.

5. Principle of proceeding from general to specific: While developing in relation to any aspect of personality, the child first picks up or exhibits general responses and learns to show specific and goal-directed responses afterwards. For example, a baby starts by waving his arms in general random movement and afterwards these general motor responses are converted into specific responses like grasping or reaching out. Similarly when a new born baby cries, his whole body is involved in doing so but as he develops, it is limited to the vocal cords, facial expression and eyes etc. In development of language, a baby calls all men daddy and all women mummy but as he grows and develops, he begins to use these names only for his own father and mother.

6. Principle of integration: By observing the principle of proceeding from general to specific or from the whole to the parts, it does not mean that only the specific responses are aimed for the ultimate consequences of one’s development. Rather, it is a sort of integration that is ultimately desired. It is the integration of the whole and its parts as well as the specific and general responses that enables a child to develop satisfactorily in relation to various aspects or dimensions of his personality.

7. Principle of interrelation: The various aspects of one’s growth and development are interrelated. What is achieved or not achieved in one or the other dimension in the course of the gradual and continuous process of development surely affects the development in other dimensions. All healthy body tends to develop a healthy mind and an emotionally stable and socially conscious personality. On the other hand, inadequate physical or mental development may results in a socially or emotionally maladjusted personality. That is why all efforts in education are always directed towards achieving harmonious growth and development in all aspects of one’s personality.

8. Principle of interaction: The process of development involves active interaction between the forces within the individual and the forces belonging to the individual. What is inherited by the organism at the time of conception is first influenced by the stimulations received in the womb of the mother and after birth, by the forces of physical and socio-psychological environment for its development. Therefore, at any stage of growth and development, the individual’s behaviour or personality make-up is nothing but the end-product of the constant interaction between his heredity endowment and environmental set-up.

9. Principle of interaction of maturation and learning: Development occurs as a result of both maturation and learning. Maturation refers to changes in an organism due to unfolding and ripening of abilities, characteristics, traits and potentialities present at birth. Learning denotes changes the changes in behaviour due to training and experience.

10. Principle of predictability: Development is predictable, which means that, to a great extent, we can forecast the general nature and behaviour of a child in one or more aspects or dimensions at any particular stage of its growth and development. Not only such prediction is possible along general lines but it is also possible to predict the range within which the future development of an individual child is going to fall. For example, with the knowledge of the development of the bones of a child it is possible to predict his adult structure and size.

11. Principle of cephalocaudal and proximodistal tendencies: Cephalocaudal and proximodistal tendencies are found to be followed in maintaining the orderly sequence and direction of developments.

According to cephalocaudal tendency, development proceeds in the direction of the longitudinal axis, ie. head to foot. For example, before it becomes able to stand, the child first gains control over his head and arms and then on his legs. In terms of proximodistal tendency, development proceeds from the near to the distant and the parts of the body near the centre develops before the extremities. For example, in the beginning the child is seen to exercise control over the large fundamental muscles of the arm and the hand and only afterwards the smaller muscles of the fingers.

12. Principle of spiral versus linear advancement. The path followed in development by the child is not straight and linear and development at any stage never takes place with a constant or steady pace. At a particular stage of his development, after the child had developed to a certain level, there is likely to be a period of rest for consolidation of the developmental progress achieved till then. In advancing further, development turns back and then moves forward again in a spiral pattern.

1.2 Growth and Development – Typical and Atypical (Physical/Individual difference)

Motor Development: Gross Motor Skills

Gross motor development, also called large motor development, refers to the development of the large muscles in the body. These are the muscles that help us sit, stand, walk, run, go up and down the stairs, and kick a ball, among many other activities.

Typically developing children usually develop gross motor skills in this order:

· holding head straight up or erect

· rolling from stomach to back, and then back to stomach

· sitting with support or assistance

· sitting without support (but with supervision!)

· creeping (i.e. moving on stomach, usually while using mostly the arms)

· crawling (i.e. moving while using both arms and legs)

· rolling a ball

· walking with both hands held by an adult

· pulling to a stand

· standing

· stopping to retrieve or collect something

· walking a few steps on their own

· walking on their own

· squatting to retrieve or collect something

· kicking a ball

· throwing and catching a ball

· climbing on and off furniture

· running

· walking upstairs and downstairs

· jumping

· walking backwards

· pedaling a tricycle or a mini-bike

· hopping forward and landing on both feet

· riding a bicycle

Motor Development: Fine Motor Skills

Fine motor skills involve the small muscles of the body, usually located in the hands. Eye/hand coordination is essential in developing fine motor skills. Fine motor development involves skills that we will need for most things we do through our life.

Motor development also includes the oral/motor area that surrounds the child’s mouth. In order for children to be able to swallow and eat properly, or to pronounce words the right way, they need to have good control over their oral/motor muscles. A child whose oral/motor muscles are either too tight (hypertonic) or too flabby (hypotonic), may require help in learning to talk, and assistance in feeding and swallowing.

Fine motor development includes the following:

· reaching for objects

· playing with hands at midline (see full Glossary)

· manipulating objects with both hands

· banging two toys together

· transferring or passing objects from one hand to the other

· picking up an object

· using the thumb and index fingers (pincer grasp) to pick small objects

· removing or taking away objects from containers

· putting objects into containers

· holding large markers with the fist

· turning pages of books

· scribbling

· opening doors

· solving simple puzzles

· stacking blocks and cups

· holding pencils using the tripod position

· building three dimensional structures with blocks

· making simple forms with play dough or clay

· nesting cups

· using scissors

· drawing simple forms

· tracing letters and numbers

· buttoning buttons

· fastening snaps

· stringing beads

· writing letters and numbers

Atypical development

Child development exists on a continuum. The development of most children falls somewhere in the “middle” of that continuum. A child is described as developing atypically when one of two situations arises:

· A child reaches developmental milestones earlier than other children his/her age

· A child reaches developmental milestones later than other children his/her age

It is very important to pay attention to children whose development is just a little bit different. They are referred to as “gray area” children because for the most part, their development is typical. This is why they may not qualify to receive services in the developmental areas in which they may be struggling, especially during their school years. It is important to monitor their progress and especially watch those areas in which they may be developing typically, but lagging a bit behind their peers.

Some signs of gross motor delay include:

Between 3 and 12 months old:

· Delay in opening hands;

· Difficulties holding head up;

· Difficulties sitting, with support or independently;

· Difficulties standing.

Between 12 – 18 months old:

· Difficulties walking and/or running;

· Difficulties going up or down the stairs;

· Difficulties with motor planning

· Difficulties with muscle tone

· Difficulties with the vestibular system

· Difficulties with the proprioceptive system

Between 18 – 36 months old:

· Difficulties kicking, throwing, rolling and catching a ball;

· Difficulties jumping and hopping;

· Difficulties with motor planning persist

· Difficulties with muscle tone persist

-Low muscle tone (i.e. hypotonia)

-High muscle tone (i.e. hypertonia)

· Difficulties with motor coordination

· Difficulties with the vestibular system vestibular system persist

· Difficulties with the proprioceptive system proprioceptive system persist

Early signs of delay in the development of fine motor skills include the following:

· Baby has difficulty latching on to breast or bottle, during feeding;

· Young baby’s hands are somewhat tight-fisted, and not open most of the time;

· Baby has difficulty taking toys to mouth, or mouthing toys;

· Toddler has difficulty using thumb and index finger, or using a pincer grasp.

Individual differences exist when it comes to the precise age at which children meet milestones; each child is unique. Milestones should not be seen as rigid checklists by which to judge or evaluate children’s development. Think of milestones as guidelines to help staff understand and identify typical patterns of development and to know when and what to look for as children mature. It is your responsibility to ensure that staff are knowledgeable about children’s developmental milestones, stay current on best practices, and use assessment data so they can meet the individual needs of the children in their classrooms. Individuals differ in height, weight, colour of skin, colour of eyes and hair, size of hands and heads, arms, feet, mouth and nose, length of waistline, structure and functioning of internal organs, facial expression, mannerisms of speech and walk, and other such native or acquired physical characteristics.

1.3 Development and deviations (Educational – Lifespan Phase) i. Pre-natal stage ii. Preschool stage iii. School stage iv. Pre-vocational stage

PRENATAL DEVELOPMENT

From beginning as a one-cell structure to your birth, your prenatal development occurred in an orderly and delicate sequence.

There are three stages of prenatal development: germinal, embryonic, and fetal.

Germinal Stage (Weeks 1–2)

In the discussion of biopsychology earlier in the book, you learned about genetics and DNA. A mother and father’s DNA is passed on to the child at the moment of conception. Conception occurs when sperm fertilizes an egg and forms a zygote. A zygote begins as a one-cell structure that is created when a sperm and egg merge. The genetic makeup and sex of the baby are set at this point. During the first week after conception, the zygote divides and multiplies, going from a one-cell structure to two cells, then four cells, then eight cells, and so on. This process of cell division is called mitosis. Mitosis is a fragile process, and fewer than one-half of all zygotes survive beyond the first two weeks. After 5 days of mitosis there are 100 cells, and after 9 months there are billions of cells. As the cells divide, they become more specialized, forming different organs and body parts. In the germinal stage, the mass of cells has yet to attach itself to the lining of the mother’s uterus. Once it does, the next stage begins.

Embryonic Stage (Weeks 3–8)

After the zygote divides for about 7–10 days and has 150 cells, it travels down the fallopian tubes and implants itself in the lining of the uterus. Upon implantation, this multi-cellular organism is called an embryo. Now blood vessels grow, forming the placenta. The placenta is a structure connected to the uterus that provides nourishment and oxygen from the mother to the developing embryo via the umbilical cord. Basic structures of the embryo start to develop into areas that will become the head, chest, and abdomen. During the embryonic stage, the heart begins to beat and organs form and begin to function. The neural tube forms along the back of the embryo, developing into the spinal cord and brain.

Fetal Stage (Weeks 9–40)

When the organism is about nine weeks old, the embryo is called a fetus. At this stage, the fetus is about the size of a kidney bean and begins to take on the recognizable form of a human being as the “tail” begins to disappear.

From 9–12 weeks, the sex organs begin to differentiate. At about 16 weeks, the fetus is approximately 4.5 inches long. Fingers and toes are fully developed, and fingerprints are visible. By the time the fetus reaches the sixth month of development (24 weeks), it weighs up to 1.4 pounds. Hearing has developed, so the fetus can respond to sounds. The internal organs, such as the lungs, heart, stomach, and intestines, have formed enough that a fetus born prematurely at this point has a chance to survive outside of the mother’s womb. Throughout the fetal stage the brain continues to grow and develop, nearly doubling in size from weeks 16 to 28. Around 36 weeks, the fetus is almost ready for birth. It weighs about 6 pounds and is about 18.5 inches long, and by week 37 all of the fetus’s organ systems are developed enough that it could survive outside the mother’s uterus without many of the risks associated with premature birth. The fetus continues to gain weight and grow in length until approximately 40 weeks. By then, the fetus has very little room to move around and birth becomes imminent. During the fetal stage, the baby’s brain develops and the body adds size and weight, until the fetus reaches full-term development.

PRESCHOOLER DEVELOPMENT (3-5 Years)

The normal social and physical development of children ages 3 to 6 years old includes many milestones. All children develop a little differently.

Physical developmental skills for preschoolers

Physical development skills are an important part of any preschool program. They include skills like:

· Muscle control, balance, and coordination (climbing ladders, opening doors, and putting on coats)

· Body awareness (sitting next to a friend rather than in her lap)

· Wellness, rest, exercise, health, and nutrition (healthy lifestyles and living)

· Self-help skills (feeding, brushing teeth, dressing, and washing hands, for example)

During the early childhood years, children learn to manage and take control of their bodies. They become more aware of what their bodies can and can’t do.

SCHOOL AGE DEVELOPMENT (6 – 12 years)

Physical development

School-age children most often have smooth and strong motor skills. However, their coordination (especially eye-hand), endurance, balance, and physical abilities vary.

Fine motor skills may also vary widely. These skills can affect a child's ability to write neatly, dress appropriately, and perform certain chores, such as making beds or doing dishes.

There will be big differences in height, weight, and build among children of this age range. It is important to remember that genetic background, as well as nutrition and exercise, may affect a child's growth.

A sense of body image begins developing around age 6. Sedentary habits in school-age children are linked to a risk for obesity and heart disease in adults. Children in this age group should get 1 hour of physical activity per day.

There can also be a big difference in the age at which children begin to develop secondary sexual characteristics.

By age 5, most children are ready to start learning in a school setting. The first few years focus on learning the fundamentals.

In third grade, the focus becomes more complex. Reading becomes more about the content than identifying letters and words.

An ability to pay attention is important for success both at school and at home. A 6-year-old should be able to focus on a task for at least 15 minutes. By age 9, a child should be able to focus attention for about an hour.

It is important for the child to learn how to deal with failure or frustration without losing self-esteem. There are many causes of school failure, including:

· Learning disabilities, such a reading disability

· Stressors, such as bullying

· Mental health issues, such as anxiety or depression

PRE VOCATIONAL STAGE (13 TO 18)

Vocational education is education that prepares people to work in a trade, in a craft, as a technician, or in support roles in professions such as engineering, accountancy, nursing, medicine, architecture, or law. Craft vocations are usually based on manual or practical activities and are traditionally nonacademic but related to a specific trade or occupation. Vocational education is sometimes referred to as career education or technical education.

Vocational education can take place at the secondary, post-secondary, further education, and higher education level; and can interact with the apprenticeship system. At the post-secondary level, vocational education is often provided by a highly specialized institute of technology/polytechnic, or by a university, or by a local community college.

Until recently, almost all vocational education took place in the classroom, or on the job site, with students learning trade skills and trade theory from accredited professors or established professionals. However, online vocational education has grown in popularity, and made it easier than ever for students to learn various trade skills and soft skills from established professionals in the industry.

Vocational training is used to prepare for a certain trade or craft. Decades ago, it used to refer solely to such fields are welding and automotive service, but today it can range from hand trades to retail to tourism management. Vocational training is education only in the type of trade a person wants to pursue, forgoing traditional academics.

Vocational training, also known as Vocational Education and Training (VET) and Career and Technical Education (CTE), provides job-specific technical training for trades, such as auto repair, plumbing and retail. These programs generally focus on providing students with hands-on instruction, and can lead to certification, a diploma or certificate.

Vocational training can also give applicants an edge in job searches, since they already have the certifiable knowledge they need to enter the field. A student can receive vocational training either in high school, a community college or at trade schools for adults.

In High School

Some vocational training is found in the form of high school CTE programs that include academic study as well as a variety of courses and work experiences designed to introduce students to trades ranging from construction, business and health services to art and design, agriculture and information technology. This form of education can be offered at high school campuses or separate vocational training centers. The ultimate goal of these programs is to prepare students for the job field and help them complete their high school education.

After High School

Community colleges and technical schools also offer a variety of vocational courses and programs. This form of instruction includes hands-on training without the added emphasis on standard subjects like math and English. Instead, students take specific classes related to the job they're training for. Vocational schools typically utilize cooperative training techniques, where students are able to work in the job they're studying for and attend classes. Most vocational training programs can be completed within six months to two years.

1.4 Intelligence & Developmental Assessment

INTELLIGENCE ASSESSMENT

Intellectual assessment and intelligence testing refer to the evaluation of an individual’s general intellectual functioning and cognitive abilities.

Intellectual Functioning

Intelligence tests provide at least one measure of ‘‘general intellectual functioning’’ and are usually administered by clinical psychologists in community settings and by school psychologists in schools. General intellectual functioning typically refers to one’s global or overall level of intelligence, often referred to as IQ (intelligence quotient). Higher IQ scores are assumed to mean that the individual has higher intellectual functioning. Unfortunately, this single score indicates general functioning. It does not necessarily explain, for example, why a given student does not know how to read even though he or she is in the fifth grade, or if the student has some special skills in an area such as art, music, or learning a foreign language. More importantly, because a global score cannot tell us in what specific area a child has difficulty or talent, it is not useful for drawing conclusions about how this child learns or should be taught. Performance on a single measure of intellectual ability might be useful as a starting point in efforts to understand a student’s skills and needs, when used in combination with other sources of information including measures of cognitive abilities.

Cognitive Abilities

One way psychologists have tried to gather information about the specific abilities that explain children’s learning and learning problems is by focusing on cognitive abilities rather than general intelligence. Cognitive abilities are those skills that make up an individual’s general intelligence. Although past theories focused on intelligence as a single global ability, modern theories view intelligence as composed of many different abilities. According to recent research, this concept of multiple abilities seems to better explain why individuals may perform very well on some types of tasks and poorly on others. See the Recommended Resources below for more information about this view of cognitive ability.

Methods of assessing intelligence

Intellectual or cognitive abilities are typically assessed using a combination of standardized tests and ecological measures.

Standardized and Norm-Referenced Tests

The most common measures of intellectual ability are standardized, norm-referenced intelligence tests, many of which yield a score where average performance is set at 100. The term IQ (or Full Scale IQ–FSIQ) is the traditional designation for these scores, which represent global intelligence and are associated most closely with the Wechsler Scales of Intelligence. Other tests use different terms for scores that mean essentially the same thing, such as General Intellectual Ability (GIA) or Mental Processing Index (MPI).

Standardized tests. Intelligence tests or batteries are made up of a series of tasks or subtests that are usually administered on an individual basis, although some group-administered tests are available. These tasks, intended to provide samples of a person’s intelligence or cognitive abilities, with each yielding a score, are referred to as standardized because each task is presented to each examinee in the same or standardized way. When standardized tests are used, performance is thought to show a person’s unique cognitive abilities, taking into account any error resulting from factors such as the individual having a bad day or imperfections in the test itself.

Norm-referenced tests. To understand how the individual compares to others, the test scores are then compared to the test’s norms. Norms are established when tests are first developed, using large groups of individuals (often reflecting characteristics of the general population in terms of age, gender, race/ethnicity, geographic region, and socioeconomic status) to determine the range of typical performance. For example, if a child gets 3 questions correct on a test of vocabulary and the norms tell us that most children of the same age correctly respond to 8 to 10 questions, we could say that this child’s vocabulary skills are poor in comparison to most children of the same age. Most intelligence tests are both norm-referenced and standardized. Typically, norm referenced intelligence tests are designed so that the mean or average score falls at 100, and about two-thirds of the population taking the test obtains scores between 85 and 115, which is considered the normal range.

Common intelligence tests. Commonly used norm referenced tests include the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI), Wechsler Intelligence for Children (WISC), Woodcock–Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities (WJ), the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scale (SB), the Differential Abilities Scale (DAS), and the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (KABC). There also exist brief measures of intelligence such as the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) and the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K–BIT). All of these measures have been updated and renormed over time. Assessments should be conducted using the most recent edition of the test to ensure up-to-date test norms.

DEVELOPMENT ASSESSMENT

Child development refers to the continuous but predictably sequential biological, psychological and emotional changes that occur in human beings between birth and the end of adolescence. Developmental surveillance should be incorporated into every child visit. Parents play an important role in the child’s developmental assessment. The primary care physician should educate and encourage parents to use the developmental checklist in the health booklet to monitor their child’s development. Further evaluation is necessary when developmental delay is identified.

Developmental assessment is detailed standardized testing in various developmental sectors done by a physician and/or allied health disciplines. It is often performed by a multi-disciplinary team that may include a developmental paediatrician, speech language pathologist, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, psychologist, audiologist and teacher. The result of the assessment is a definitive description of specific developmental levels, often given as age equivalents, and formulation of an intervention plan.

Purposes of Developmental Assessments:

· Identifying and diagnosing a global intellectual delay: this may include determining the severity of an intellectual impairment and evaluating the impact this is having on meeting developmental milestones. Re-administering assessments can also provide a standardised method to monitor an individual’s progress over time.

· Developing individualised management programs: by identifying a child’s strengths and weaknesses, the psychologist can work with parents and teachers to develop interventions to best accommodate a child’s learning and developmental needs.

· Accessing additional funding: the diagnosis of a developmental disability can assist with accessing government funding and school based funding to provide the necessary supports in the home and school environment to best accommodate the child’s needs.

· In combination with cognitive assessments: developmental assessments can also be administered in conjunction with cognitive assessments to determine whether difficulties in particular areas can be explained by an intellectual disability or learning disorder.

Assessment Process

To accurately identify and diagnose a developmental delay or disorder, a standardised psychometric assessment is used to assess various areas of development such as:

· Communication: speaking and listening skills used to convey messages to others

· Social: skills required to interact and get along with others, including being emotionally attuned

· Self-care: skills needed for personal care including eating, dressing and bathing

· Self-direction: skills needed for independence and self-control

· Motor: includes both gross motor skills such as crawling and sitting and fine motor skills such as gripping and pointing

Along with psychometric tools, a comprehensive assessment also requires a consultation process that typically a developmental history interview with parents and teacher consultations. The results of the assessment are provided in a written report and the Psychologist will discuss any identified needs and recommended interventions.

Assessment Tools

There are various developmental assessment tools that are used for various purposes and age groups. We commonly use the following developmental assessment tools:

· Adaptive Behaviour Assessment System: – Third Edition (ABAS-III) to assess adaptive functioning for individuals aged 0 to 89 years.

· The Bayley Scales of Infant Development: – Third Edition (Bayley-III) to assess children from one month old to 3.5 years.

· The Griffith Mental Development Scales (GMDS): to assess the rate of development of infants and young children from birth to 8 years.

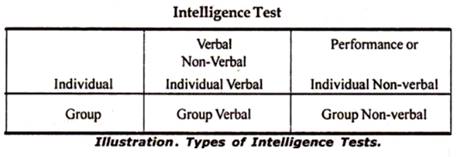

1.5 Types of Intelligence Test

Intelligence tests may be classified under three categories:

1. Individual Tests:

These tests are administered to one individual at a time. These cover age group from 2 years to 18 years.

These are:

(a) The Binet- Simon Tests,

(b) Revised Tests by Terman,

(c) Mental Scholastic Tests of Burt, and

(d) Wechsler Test.

2. Group Tests:

Group tests are administered to a group of people Group tests had their birth in America – when the intelligence of the recruits who joined the army in the First World War was to be calculated.

These are:

(a) The Army Alpha and Beta Test,

(b) Terman’s Group Tests, and

(c) Otis Self- Administrative Tests.

Among the group tests there are two types:

(i) Verbal, and

(ii) Non-Verbal.

Verbal tests are those which require the use of language to answer the test items.

3. Performance:

These tests are administered to the illiterate persons. These tests generally involve the construction of certain patterns or solving problems in terms of concrete material.

Some of the famous tests are:

(a) Koh’s Block Design Test,

(b) The Cube Construction Tests, and

(c) The Pass along Tests

![]()