Unit 3: Process of Intellectual Development

3.1 Concept, meaning, definition and theories of Cognition

3.2 Concept, meaning, definition and theories of Learning

3.3 Concept, meaning, definition and theories of Intelligence

3.4 Concept, meaning, definition and stages of Language Development

3.5 Concept, meaning, definition and theories of Memory

3.1 Concept, meaning, definition and theories of Cognition

Cognition is simply defined as our thinking process. It describes the very act of acquiring knowledge through perception, thinking, imagination, remembering, judging, problem-solving, and selective attention. Cognition is one of the higher functions that our brain performs. In recent years, the study of cognition has become a sub-discipline of psychology known as cognitive psychology.

Cognitive psychology uses scientific methods to study mental processes. It also acknowledges the idea that thoughts, feelings, and beliefs can sometimes determine emotion and behavior. To change the way people behave; thoughts, beliefs, and 'knowing' may need to be changed.

Cognitive theories of human behavior and decision-making models became popular in the early 1970s and 1980s as a response to behaviorism.

The cognitive psychologist studies human perceptions and the ways in which cognitive processes operate to produce responses. Cognitive processes (which may involve language, symbols, or imagery) include perceiving, recognizing, remembering, imagining, conceptualizing, judging, reasoning, and processing information for planning, problem-solving, and other applications. Some cognitive psychologists may study how internal cognitive operations can transform symbols of the external world, others on the interplay between genetics and environment in determining individual cognitive development and capabilities. Still other cognitive psychologists may focus their studies on how the mind detects, selects, recognizes, and verbally represents features of a particular stimulus. Among the many specific topics investigated by cognitive psychologists are language acquisition; visual and auditory perception; information storage and retrieval; altered states of consciousness; cognitive restructuring (how the mind mediates between conflicting, or dissonant, information); and individual styles of thought and perception.

Since the 1950s, cognitive approaches have assumed a central place in psychological research and theorizing. One of its foremost pioneers is Jerome Bruner, who, together with his colleague Leo Postman, did important work on the ways in which needs, motivations, and expectations (or "mental sets") affect perception. Bruner's work led him to an interest in the cognitive development of children and related issues of education, and he later developed a theory of cognitive growth. His theories, which approached development from a different angle than—and mostly complement—those of Piaget, focus on the environmental and experiential factors influencing each individual's specific development pattern.

Piaget's Theory: The Four Stages of Cognitive Development

The term cognition is derived from the Latin word “cognoscere” which means “to know” or “to recognize” or “to conceptualize”. It refers to the mental processes an organism learns, remembers, understands, perceives, solves problems and thinks about a body of information.

Piaget's (1936) theory of cognitive development is about how a child constructs a mental model of the world.

There Are Three Basic Components To Piaget's Cognitive Theory:

1. Schemas (building blocks of knowledge).

2. Adaptation processes that enable the transition from one stage to another (equilibrium, assimilation and accommodation).

3. Stages of Development:

o sensorimotor,

o preoperational,

o concrete operational,

o formal operational.

Schemas

Piaget (1952) defined a schema as:

'a cohesive, repeatable action sequence possessing component actions that are tightly interconnected and governed by a core meaning'.

In more simple terms Piaget called the schema the basic building block of intelligent behavior – a way of organizing knowledge. For example, a person might have a schema about buying a meal in a restaurant. The schema is a stored form of the pattern of behavior which includes looking at a menu, ordering food, eating it and paying the bill. This is an example of a type of schema called a 'script'. Whenever they are in a restaurant, they retrieve this schema from memory and apply it to the situation.

Three processes work together from birth to propel development forward. Jean Piaget viewed intellectual growth as a process of adaptation (adjustment) to the world. This happens through:

Assimilation: The process by which people translate incoming information into a form they can understand. Which is using an existing schema to deal with a new object or situation. A 2 year old child sees a man who is bald on top of his head and has long frizzy hair on the sides. To his father’s horror, the toddler shouts “Clown, clown”

Accommodation: The process by which people adapt current knowledge structures in response to new experiences. This happens when the existing schema (knowledge) does not work, and needs to be changed to deal with a new object or situation. In the “clown” incident, the boy’s father explained to his son that the man was not a clown and that even though his hair was like a clown’s, he wasn’t wearing a funny costume and wasn’t doing silly things to make people laugh.

With this new knowledge, the boy was able to change his schema of “clown” and make this idea fit better to a standard concept of “clown”.

Equilibration: The process by which people balance assimilation and accommodation to create stable understanding. Equilibrium occurs when a child's schemas can deal with most new information through assimilation. However, an unpleasant state of disequilibrium occurs when new information cannot be fitted into existing schemas (assimilation).

Stages of Development

Piaget believed that children go through 4 universal stages of cognitive development.

1. Sensorimotor stage (Infancy), from birth to age 2

· Understands world through senses and actions

· The main achievement during this stage is object permanence - knowing that an object still exists, even if it is hidden.

· It requires the ability to form a mental representation (i.e. a schema) of the object.

2. Pre-operational stage (Toddler and early childhood), from age 2 to about age 7

· Understands world through language and mental images

· During this stage, young children are able to think about things symbolically. This is the ability to make one thing - a word or an object - stand for something other than itself.

· Thinking is still egocentric, and the infant has difficulty taking the viewpoint of others.

3. Concrete operational stage(Elementary and early adolescence), from 7-11

· Understands world through logical thinking and categories

· Piaget considered the concrete stage a major turning point in the child's cognitive development, because it marks the beginning of logical or operational thought.

· This means the child can work things out internally in their head (rather than physically try things out in the real world).

· Children can conserve number (age 6), mass (age 7), and weight (age 9). Conservation is the understanding that something stays the same in quantity even though its appearance changes

4. Formal operational stage (Adolescence and adulthood).

· Understands world through hypothetical thinking and scientific reasoning

· The formal operational stage begins at approximately age eleven and lasts into adulthood. During this time, people develop the ability to think about abstract concepts, and logically test hypotheses.

Because Piaget's theory is based upon biological maturation and stages, the notion of 'readiness' is important. Readiness concerns when certain information or concepts should be taught. According to Piaget's theory children should not be taught certain concepts until they have reached the appropriate stage of cognitive development.

According to Piaget (1958), assimilation and accommodation require an active learner, not a passive one, because problem-solving skills cannot be taught, they must be discovered.

Therefore, teachers should encourage the following within the classroom:

· Focus on the process of learning, rather than the end product of it.

· Using active methods that require rediscovering or reconstructing "truths".

· Using collaborative, as well as individual activities (so children can learn from each other).

· Devising situations that present useful problems, and create disequilibrium in the child.

· Evaluate the level of the child's development, so suitable tasks can be set.

· Although Piaget's theory remains highly influential, some weaknesses are now apparent.

· The stage model depicts children's thinking as being more consistent than it is. Infants and young children are more cognitively competent than Piaget recognized. Piaget's theory understates the contribution of the social world to cognitive development.

· Piaget's theory is vague about the cognitive processes that give rise to children's thinking and about the mechanisms that produce cognitive growth.

Bruner's Theory of Cognitive Development

Bruner – Modes of Representation rather than stages – knowledge and understanding can take 3 different forms:

Enactive, Iconic and Symbolic modes

Enactment Mode

· A baby represents world through actions = (sensorimotor stage from Piaget’s theory

· Knowledge stored as “muscle memory” – baby may carry on shaking arm even if you take rattle away – thought arm movement made the noise!

· Our knowledge for motor skills (eg riding a bike) are represented in the enactive mode.

· They become automatic through repetition. Like Piaget, Bruner sees onset of object permanence = a major qualitative change in way child thinks.

Iconic Mode

· Knowledge represented through visual or auditory images – icons. Relates to last 6 months of sensorimotor + all of pre-op stage.

· Baby can represent rattle as a visual image so it is now an independent “thing” = object permanence.

· child’s thinking is dominated by images -things are as they look in this mode.

Symbolic Mode

· Like Piaget, major change at 6/7 yrs – language starts to influence thought.

· Not so dominated by appearance of things – can think beyond images and use symbols such as words or numbers.

· Information can now be categorized and summarized – can be more readily manipulated.

Bruner’s theory - key points

Development involves mastery of increasingly more complex modes of thinking from enactive to symbolic

As skills learned they become automatic and become units that can be combined to build up a new set of skilled behaviours

Learning not a gradual process - more like a staircase - sharp steps up - Environment rather than age that slows down or accelerates learning ( something clicks to unlock understanding)

The organisation of knowledge - thinking based on categorisation (similarities and differences - system of coding to store info). Hierarchy -general at top getting more specific e.g classification of animals

Cultural Differences - he explained this in his book ‘The Culture of Education’ by suggesting that people from different cultures make sense of their experiences in different ways because of the differences in the society in which they live. They internalise their surrounding culture e.g. Categorisation structures for birds may be different in UK and Africa

Paradigmatic (analytic) and Narrative (intuitive)Thinking –

Paradigmatic - based on logic, traditional type of thinking emphasised in schools, leads to construction of categories and hierarchies

Narrative - more interpretive, complex and rich phenomena of life better represented in stories or narratives. Paradigmatic and narrative complement each other, but Paradigmatic may block the ability to think narratively, as it makes us look for patterns and logic rather than looking at things subjectively and creatively (Gardner 1982)

|

BRUNER AGREES WITH PIAGET |

BRUNER DISAGREES WITH PIAGET |

|

1. Children are PRE-ADAPTED to learning |

1. Development is a CONTINUOUS PROCESS – not a series of stages |

|

2. Children have a NATURAL CURIOSITY |

2. The development of LANGUAGE is a cause not a consequence of cognitive development |

|

3. Children’s COGNITIVE STRUCTURES develop over time |

3. You can SPEED-UP cognitive development. You don’t have to wait for the child to be ready |

|

4. Children are ACTIVE participants in the learning process |

4. The involvement of ADULTS and MORE KNOWLEDGEABLE PEERS makes a big difference |

|

5. Cognitive development entails the acquisition of SYMBOLS |

5. Symbolic thought does NOT REPLACE EARLIER MODES OF REPRESENTATION |

3.2 Concept, meaning, definition and theories of Learning

Learning Theory describes how students absorb, process, and retain knowledge during learning. Cognitive, emotional, and environmental influences, as well as prior experience, all play a part in how understanding, or a world view, is acquired or changed and knowledge and skills retained.

Theories of learning have done much to influence the way people teach, create course curriculum and explain things to their children. Theories have sprung up that reflect the changing values in our social environments and the popular influences of the day. In the 1960s, cognitivism moved to the forefront of learning theory, exactly when popular culture was embracing “do your own thing.” Behavioralism, a more basic reward-and-learn postulation, became a little less popular about then.

Learning theories are very persistent. Many explanations have been devised to define the same phenomenon, possibly because learning is complex and one theory does not fit everyone or every situation. Here are five prominent theories that attempt to explain how we go to bed at night a little smarter than when we woke up that morning.

1. Behaviorism: Key Theorists- Edward Thorndike, Ivan Pavlov, John B. Watson, and B.F. Skinner

Behaviorism dates back to the late 19th century and, as such, was born in an era when natural sciences were at the forefront of scientific discovery. It explains learning as a conditioned or operant response to the environment, which supplies either positive or negative consequences to any behavior. It also postulates that learning is only complete when it can be seen as a change in behavior.

Behaviorism postulates learning as starting with a blank page. American psychologist B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) argued that the theory was incomplete, however, because it did not explain how we overcome initial failures to do things like ride a bicycle. Skinner added the concept that prior thought and emotions also came into play for human learning. Because of this, Skinner’s work was sometimes labeled “radical behaviorism.”

2. Cognitivism: Key Theorists- Jean Piaget, Jerome Bruner, Robert Mills Gagne, Marriner David Merill, Charles Reigeluth, and Roger Schank.

Cognitivism is often tied to behaviorism in practice, but the theories are polar opposites. Cognitivism explains learning as based on understanding. The mind, when receptive to new ideas, actively processes new information to arrive at an understanding that relies on incorporating prior knowledge and assumptions. This puts thinking at the forefront of the learning process. Learning is evidenced by new understanding, not behavioral change.

Cognitivism relies on a process in which new information is weighed against prior knowledge. How does new information fit in with previously learned information? This brings into play processes like problem solving, analysis and memory.

Understanding is defined as a cognitive “schema,” which is analogous to awareness or meaning. Learning is defined as a change in an established schema.

3. Constructivism: Key Theorists- John Dewey, Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, and Jerome Bruner

Like cognitivism, constructivism sees learning as an active mental process. Under contructivism theory, people build or construct knowledge based on social or situational experiences. This allows people to accumulate information and to test it through social interactions.

In this manner, it would seem that knowledge would eventually homogenize. But that isn’t the case. Constructivism says people build knowledge based on subjective considerations. Individuals then come to individual, subjective conclusions. Knowledge is still viewed as a conceptualized process with learning seen as the result of interactions with the environment and the constant testing that we rely on to process information.

4. Social and Contextual: Key Theorists - Lev Vygotsky, Albert Bandura, Jean Lave, Rogoff, Etienne Wenger, and Thomas Sergiovanni

First emerging in the late 20th century, social and contextual learning theories challenge the individual-focused approaches evident in both constructivism and cognitivism. Social and contextual theories are influenced by anthropological and ethnographic research and emphasize the ways environment and social contexts shape one's learning.

In this view, cognition and learning are understood as interactions between the individual and a situation; knowledge is situated in — and a product of — the activity, context, and culture in which it is developed and used. This led to new metaphors for learning as a "participation" and "social negotiation."

Social learning theory pays particular attention to social and interactive aspects of learning. Albert Bandura, for example, emphasizes the roles that social observation and modeling play in learning, while Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger posit that learning works best in a community of practice that produces social capital that improves the health of the community and its members.

5. Experiential: Key Theorists- David A. Kolb and Carl Rogers

Espoused by educational theorist David Kolb, experiential theory sees learning as a four-step process that includes concrete experiences, reflective observation, abstract conceptualism and active experimentation. Here, experience leads to reflection, then conceptualization, then testing, which involves new experiences. It is seen as a self-sustaining cycle with each of the four steps required for learning.

Kolb also says emotions, prior learning and style of processing are involved. As such, there are four learning styles. Some people prefer doing; others prefer watching. Some prefer reading and reflecting. Others prefer a gut-level response followed by experimenting. This theory gave birth to multi-modality teaching. Experiential teachers deploy hands on learning, reflections, reading, watching slides or films, lectures, field trips, and other methods to accommodate all their students’ learning styles.

3.3 Concept, meaning, definition and Theories of Intelligence

Human intelligence, mental quality that consists of the abilities to learn from experience, adapt to new situations, understand and handle abstract concepts, and use knowledge to manipulate one’s environment.

A typical dictionary definition of Intelligence is “the capacity to acquire and apply knowledge.” Intelligence includes the ability to benefit from past experience, act purposefully, solve problems, and adapt to new situations. Intelligence can also be defined as “the ability that intelligence tests measure.” There is a long history of disagreement about what actually constitutes intelligence.

Theories of intelligence, as is the case with most scientific theories, have evolved through a succession of models. Four of the most influential paradigms have been psychological measurement, also known as psychometrics; cognitive psychology, which concerns itself with the processes by which the mind functions; cognitivism and contextualism, a combined approach that studies the interaction between the environment and mental processes; and biological science, which considers the neural bases of intelligence.

Psychometric theories

Psychometric theories have generally sought to understand the structure of intelligence: What form does it take, and what are its parts, if any? Such theories have generally been based on and established by data obtained from tests of mental abilities, including analogies. Psychometric theories are based on a model that portrays intelligence as a composite of abilities measured by mental tests. This model can be quantified. For example, performance on a number-series test might represent a weighted composite of number, reasoning, and memory abilities for a complex series. Mathematical models allow for weakness in one area to be offset by strong ability in another area of test performance. In this way, superior ability in reasoning can compensate for a deficiency in number ability.

One of the earliest of the psychometric theories came from the British psychologist Charles E. Spearman (1863–1945), who published his first major article on intelligence in 1904. He noticed what may seem obvious now—that people who did well on one mental-ability test tended to do well on others, while people who performed poorly on one of them also tended to perform poorly on others. To identify the underlying sources of these performance differences, Spearman devised factor analysis, a statistical technique that examines patterns of individual differences in test scores. He concluded that just two kinds of factors underlie all individual differences in test scores. The first and more important factor, which he labeled the “general factor,” or g, pervades performance on all tasks requiring intelligence. In other words, regardless of the task, if it requires intelligence, it requires g. The second factor is specifically related to each particular test.

The American psychologist L.L. Thurstone disagreed with Spearman’s theory, arguing instead that there were seven factors, which he identified as the “primary mental abilities.” These seven abilities, according to Thurstone, were verbal comprehension (as involved in the knowledge of vocabulary and in reading), verbal fluency (as involved in writing and in producing words), number (as involved in solving fairly simple numerical computation and arithmetical reasoning problems), spatial visualization (as involved in visualizing and manipulating objects, such as fitting a set of suitcases into an automobile trunk), inductive reasoning (as involved in completing a number series or in predicting the future on the basis of past experience), memory (as involved in recalling people’s names or faces, and perceptual speed (as involved in rapid proofreading to discover typographical errors in a text).

Cognitive theories

During the era dominated by psychometric theories, the study of intelligence was influenced most by those investigating individual differences in people’s test scores. In an address to the American Psychological Association in 1957, the American researcher Lee Cronbach, a leader in the testing field, decried the lack of common ground between psychologists who studied individual differences and those who studied commonalities in human behaviour. Cronbach’s plea to unite the “two disciplines of scientific psychology” led, in part, to the development of cognitive theories of intelligence and of the underlying processes posited by these theories.

Cognitive-contextual theories

Cognitive-contextual theories deal with the way that cognitive processes operate in various settings. Two of the major theories of this type are that of the American psychologist Howard Gardner and that of Sternberg. In 1983 Gardner challenged the assumption of a single intelligence by proposing a theory of “multiple intelligences.” Earlier theorists had gone so far as to contend that intelligence comprises multiple abilities. But Gardner went one step farther, arguing that intelligences are multiple and include, at a minimum, linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal intelligence.

Biological theories

The theories discussed above seek to understand intelligence in terms of hypothetical mental constructs, whether they are factors, cognitive processes, or cognitive processes in interaction with context. Biological theories represent a radically different approach that dispenses with mental constructs altogether. Advocates of such theories, usually called reductionists, believe that a true understanding of intelligence is possible only by identifying its biological basis. Some would argue that there is no alternative to reductionism if, in fact, the goal is to explain rather than merely to describe behaviour. But the case is not an open-and-shut one, especially if intelligence is viewed as something more than the mere processing of information. As Howard Gardner pointedly asked in the article “What We Do & Don’t Know About Learning” (2004):

Can human learning and thinking be adequately reduced to the operations of neurons, on the one hand, or to chips of silicon, on the other? Or is something crucial missing, something that calls for an explanation at the level of the human organism?

Analogies that compare the human brain to a computer suggest that biological approaches to intelligence should be viewed as complementary to, rather than as replacing, other approaches. For example, when a person learns a new German vocabulary word, he becomes aware of a pairing, say, between the German term Die Farbe and the English word colour, but a trace is also laid down in the brain that can be accessed when the information is needed. Although relatively little is known about the biological bases of intelligence, progress has been made on three different fronts, all involving studies of brain operation.

3.4 Concept, meaning, definition and stages of Language Development

Language is a communication system that involves using words and systematic rules to organize those words to transmit information from one individual to another. While language is a form of communication, not all communication is language. Many species communicate with one another through their postures, movements, odors, or vocalizations. This communication is crucial for species that need to interact and develop social relationships with their conspecifics. However, many people have asserted that it is language that makes humans unique among all of the animal species.

Language

development is the process by which children come to understand and communicate

language during early childhood.

From birth up to the age of five, children develop language at a very rapid

pace. The stages of language development are universal among humans. However,

the age and the pace at which a child reaches each milestone of language

development vary greatly among children. Thus, language development in an

individual child must be compared with norms rather than with other individual

children. In general girls develop language at a faster rate than boys. More

than any other aspect of development, language development reflects the growth

and maturation of the brain. After the age of five it becomes much more

difficult for most children to learn language.

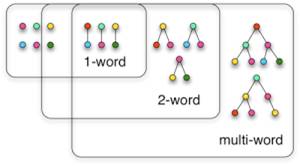

Receptive language development (the ability to comprehend language) usually develops faster than expressive language (the ability to communicate). Two different styles of language development are recognized. In referential language development, children first speak single words and then join words together, first into two-word sentences and then into three-word sentences. In expressive language development, children first speak in long unintelligible babbles that mimic the cadence and rhythm of adult speech. Most children use a combination these styles.

Stages

of Language Acquisition

There are four main stages of normal language acquisition: The babbling stage, the Holophrastic or one-word stage, the two-word stage and the Telegraphic stage. These stages can be broken down even more into these smaller stages: pre-production, early production, speech emergent, beginning fluency intermediate fluency and advanced fluency. On this page I will be providing a summary of the four major stage of language acquisition.

Babbling

Within a few weeks of being born the baby begins to recognize it’s mothers’ voice. There are two sub-stages within this period. The first occurs between birth – 8 months. Most of this stage involves the baby relating to its surroundings and only during 5/6 – 8 month period does the baby begin using it’s vocals. As has been previously discussed babies learn by imitation and the babbling stage is just that. During these months the baby hears sounds around them and tries to reproduce them, albeit with limited success. The babies attempts at creating and experimenting with sounds is what we call babbling. When the baby has been babbling for a few months it begins to relate the words or sounds it is making to objects or things. This is the second sub-stage. From 8 months to 12 months the baby gains more and more control over not only it’s vocal communication but physical communication as well, for example body language and gesturing. Eventually when the baby uses both verbal and non-verbal means to communicate, only then does it move on to the next stage of language acquisition.

Holophrastic / One-word stage

The second stage of language acquisition is the holophrastic or one word stage. This stage is characterized by one word sentences. In this stage nouns make up around 50% of the infants vocabulary while verbs and modifiers make up around 30% and questions and negatives make up the rest. This one-word stage contains single word utterances such as “play” for “I want to play now”. Infants use these sentence primarily to obtain things they want or need, but sometimes they aren’t that obvious. For example a baby may cry or say “mama” when it purely wants attention. The infant is ready to advance to the next stage when it can speak in successive one word sentences.

Two-Word Stage

The two word stage (as you may have guessed) is made of up primarily two word sentences. These sentences contain 1 word for the predicate and 1 word for the subject. For example “Doggie walk” for the sentence “The dog is being walked.” During this stage we see the appearance of single modifiers e.g. “That dog”, two word questions e.g. “Mummy eat?” and the addition of the suffix –ing onto words to describe something that is currently happening e.g. “Baby Sleeping.”

Telegraphic Stage

The final stage of language acquisition is the telegraphic stage. This stage is named as it is because it is similar to what is seen in a telegram; containing just enough information for the sentence to make sense. This stage contains many three and four word sentences. Sometime during this stage the child begins to see the links between words and objects and therefore overgeneralization comes in. Some examples of sentences in the telegraphic stage are “Mummy eat carrot”, “What her name?” and “He is playing ball.” During this stage a child’s vocabulary expands from 50 words to up to 13,000 words. At the end of this stage the child starts to incorporate plurals, joining words and attempts to get a grip on tenses.

As a child’s grasp on language grows it may seem to us as though they just learn each part in a random order, but this is not the case. There is a definite order of speech sounds. Children first start speaking vowels, starting with the rounded mouthed sounds like “oo” and “aa”. After the vowels come the consonants, p, b, m, t, d, n, k and g. The consonants are first because they are easier to pronounce then some of the others, for example ‘s’ and ‘z’ require specific tongue place which children cannot do at that age.

As all human beings do, children will improvise something they cannot yet do. For example when children come across a sound they cannot produce they replace it with a sound they can e.g. ‘Thoap” for “Soap” and “Wun” for “Run.” These are just a few example of resourceful children are, even if in our eyes it is just cute

3.5 Concept, meaning, definition and theories of Memory

Among the great primordial concepts of psychology, few are so badly abused and poorly understood today as is “memory.” It is the word “memory” which is in this deplorable condition, not so much our knowledge of the realities to which the term has been applied, though to be sure there are many subtleties in these phenomena which still elude us and will continue to do so until the language in which we think about them is rehabilitated. In our technical and quasi-technical usage of “memory” and such related expressions as “remembering,” “memories,” “memory trace,” “recall,” “retention,” “learning,” and “information storage,” a number of fundamental distinctions and not-so-fundamental metaphors have become jumbled together in a monstrous snarl of ambiguity and confusion. This paper is an effort to tease apart the more important strands of this tangle.

Types of Memory

Sensory Memory

Sensory memory allows individuals to retain impressions of sensory information after the original stimulus has ceased. One of the most common examples of sensory memory is fast-moving lights in darkness: if you’ve ever lit a sparkler on the Fourth of July or watched traffic rush by at night, the light appears to leave a trail. This is because of “iconic memory,” the visual sensory store. Two other types of sensory memory have been extensively studied: echoic memory (the auditory sensory store) and haptic memory (the tactile sensory store). Sensory memory is not involved in higher cognitive functions like short- and long-term memory; it is not consciously controlled. The role of sensory memory is to provide a detailed representation of our entire sensory experience for which relevant pieces of information are extracted by short-term memory and processed by working memory.

Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory is also known as working memory. It holds only a few items (research shows a range of 7 +/- 2 items) and only lasts for about 20 seconds. However, items can be moved from short-term memory to long-term memory via processes like rehearsal. An example of rehearsal is when someone gives you a phone number verbally and you say it to yourself repeatedly until you can write it down. If someone interrupts your rehearsal by asking a question, you can easily forget the number, since it is only being held in your short-term memory.

Long-Term Memory

Long-term memories are all the memories we hold for periods of time longer than a few seconds; long-term memory encompasses everything from what we learned in first grade to our old addresses to what we wore to work yesterday. Long-term memory has an incredibly vast storage capacity, and some memories can last from the time they are created until we die.

There are many types of long-term memory. Explicit or declarative memory requires conscious recall; it consists of information that is consciously stored or retrieved. Explicit memory can be further subdivided into semantic memory (facts taken out of context, such as “Paris is the capital of France”) and episodic memory (personal experiences, such as “When I was in Paris, I saw the Mona Lisa“).

In contrast to explicit/declarative memory, there is also a system for procedural/implicit memory. These memories are not based on consciously storing and retrieving information, but on implicit learning. Often this type of memory is employed in learning new motor skills. An example of implicit learning is learning to ride a bike: you do not need to consciously remember how to ride a bike, you simply do. This is because of implicit memory.

Three Main Theories are:

1. Theory of General Memory Process

2. Information-processing Theories

3. Levels of Processing Theory.

Several theories have been proposed by psychologists to explain how we remember or how memory works.

These theories are useful in giving information accumulated by psychologists about memory.

1. Theory of General Memory Process:

This theory explains that the memory consists of the three cognitive processes. These are— An encoding process, a storage process and a retrieval process.

Encoding is the process of receiving a sensory input and transforming it into a form, or a code which can be stored.

Storage is the process of actually putting coded information into memory. Retrieval is the process of gaining access to the stored, coded information when it is needed.

2. Information-processing Theories:

The ideas about memory that emphasize the processing of information in stages, or steps are known as information-processing theories or models. A number of such models have been proposed. The most prominent among them is the storage and transfer model developed by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968).

Storage and transfer model:

In this model, Atkinson and Shiffrin have suggested three different memory storage systems: Sensory stores, a short-term store and a long-term store.

According to this model the process of memorisation starts with picking up of information by our sense organs from the environment. Then this information will travel through nervous system and reaches the brain where it is evaluated.

The sensory information must stay in nervous system for very short duration, approximately for less than a second to allow the brain to interpret. This stage is called sensory storage.

Then this information is passed on to the short-term store where it is held for about 30 seconds. Some of the information reaching short-term memory is processed by being rehearsed-that is, having attention focused on it, being repeated over and over, and this is a conscious activity. The information not so processed is lost. Finally the information rehearsed may then be passed on to long-term store.

When information is placed in long-term store, it is recognized into categories, where they may reside for days, months, years or for a lifetime. This long-term store is assumed to have almost unlimited capacity for the storage.

This organised and stored information in the long-term store which is in the coded form is transferred back to the short-term store, where it is decoded and employed for response as ordered by the brain through motor nerves.

3. Levels of Processing Theory:

This theory was suggested by Craik and Lokhart (1972). According to this theory, there is only one kind of memory, and the ability to remember depends upon the depth of information processing.

If the information is processed in a superficial and shallow level, the forgetting will be more, and on the other hand, if the information is processed deeply, it will remain in memory for long time and helps us to remember when needed.